A New Model for Long-term Care Design: A Household Case Study

Abstract

Background Nursing homes are a prevalent component of the United States health care system. New models for providing skilled care services are being developed to respond to the increasing demand for better housing and service options for frail elderly persons. These new models are being referred to as “households” (HH) and the philosophy of the practices revolves around a self-directed model called “person-centered care” (PCC). This research paper presents a case study of a HH model for nursing home design that incorporated PCC practices. An articulation of four highly regulated routines common to all nursing home services will demonstrate where congruence and incongruence exist between the organizational and environmental design strategies as well as with the existing regulatory framework.

Methods A case study methodology was applied for this inquiry. A qualitative research design using a mixed-methods strategy was employed that included (1) ethnographic tactics of participant observation and open-ended staff interviews; (2) structured interviews with administrative personnel; (3) archival search and schematic articulation of the setting; and (4) photo-documentation of the composition of the HH features, spaces, and equipment that were integral in four routines. Using a mixed method approach allowed for triangulation of the analysis of the collected data.

Result It was observed that care staff must participate in multiple roles within the HH in order to achieve the goal of PCC. It was also observed that staff assigned to the HH as well as staff outside the HH were integral in many of the routines that support the residents’ daily need. The evidence also revealed that there were multiple examples of both congruence and incongruence between the organizational and environmental design. Some routines were modified to meet existing regulatory requirements due to a lack of “fit” between the environmental features of the HH and the operational rules. The overall environmental design of the HH did, however, create a new expectation for the work, and a difference in meaning of place was reported.

Conclusions This case study reinforces the importance of recognizing the role the environment plays in supporting the work of care staff and the organization’s goals for PCC. This study also provide evidence that it is no longer acceptable to make assumptions about practices that may not be practical in HHs without the proper environmental and organizational supports. The routines of care settings may have the same purpose, but the nature of work in HHs changes, and therefore, assumptions about this work as well as the environment must also change.

Keywords:

Nursing Homes, Household Models, Person-Centered Care, Organizational Design, Environmental Design1. Introduction

Nursing homes for the elderly and disabled have had a long history as part of the United States health care system. These institutions became prominent during the Industrial era and were developed in response to public concerns about quality standards for caring for frail elderly who needed both housing and medical services (Haber & Gratton, 1994). Because these places were patterned after American hospitals, the predominant focus of services were medical practices and the buildings were designed around these clinical activities. As a result, expectations for the social dimensions of life were often ignored (Vladek, 2003; Meyer, 2006; Lustbader, 2001).

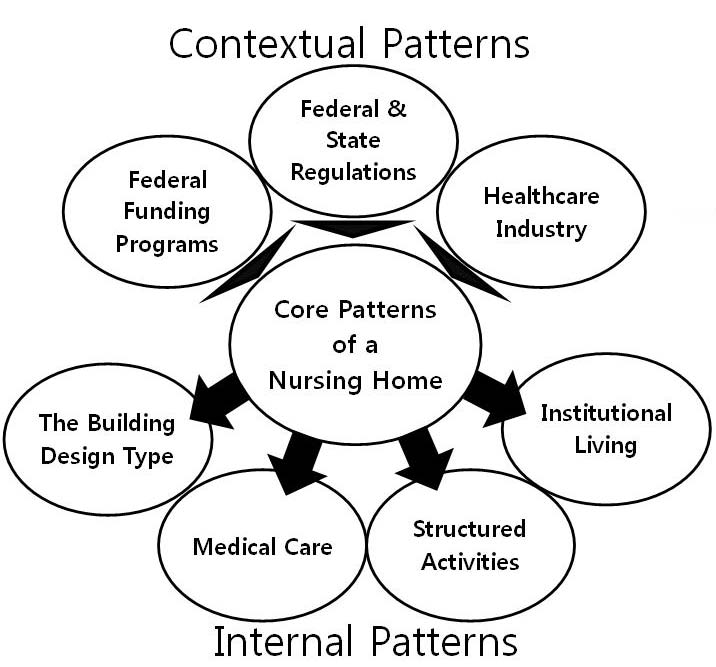

There are still hundreds of nursing homes that continue to be structured around this medical model. Emphasis has also continued to be placed on adhering to strict regulatory guidelines, implementing clinical standards, and following staff directed schedules. These contextual patterns form what Silverstein and Jacobson (1985) refer to as a “hidden program” of the place as it sets up a system of relationships that give a building its basic socio-physical form and connect it to the rest of society (See Figure 1.).

Hidden Program of Long-term Care Services (based on conceptual model of Silverstein & Jaconbson’s Hidden Program, 1985)

As America anticipates an increase in its aging population in the coming years, nursing homes will continue to be an important place-type. Societal expectations for long-term care services are, however, starting to demand that more attention be directed at the quality of life for elders who call these places their home (Talerico, O’Brien, & Swafford, 2003, p.12). In response, some providers are testing new models that include changing the design of the nursing home building as well as the manner in which care staff provide services. These new models are being referred to as “households” (HH) and the philosophy of the practices revolves around a self-directed model called “Person-Centered Care” (PCC). This self-directed philosophy emphasizes the elders’ rights in making choices about their daily activities and the manner in which they receive care services. This approach also emphasizes an increased autonomy for all care staff to respond to resident requests without having to get prior approval from upper administrative personnel. Nursing homes must still continue to adhere to multiple regulatory guidelines if they want to receive funding from federal and state agencies (Hovey, 2000), and it can be a challenge to make sure that new approaches to housing and care fit within the existing regulatory requirements.

Central to PCC is the expression of desired patterns of behavior through features of the built environment. The implications for the setting, specifically the interior environment, are beginning to be addressed as an important factor in supporting new behavioral expectations (Pekkarinen, Sinervo, Perala, & Elovainio, 2004; Rantz, et al., 2004; Arling, Kane, Mueller, Bershadsky, & Degenholtz, 2007). Initial evaluations on early HH models demonstrate that the built environment impacts workflow and the organizational structure (Kane, Lum, Cutler, Degenholtz, & Yu, 2007, p. 832; Rabig et al., 2006, p. 354; Pekkarinen, et al., 2004, p. 638). There are also demonstrated variations in both organizational structure and environmental fit. A supportive environment appears to be critical for PCC practices, and the ability to provide services in this manner is dependent upon characteristics of the system in which care is provided. Little is known, to date, about the inter-relationship between the parts of the organizational system and the actual practices that can be supported through the HH model.

This research presents a case study of a HH model for nursing home design that incorporated PCC practices. An articulation of four highly regulated routines common to all nursing home services will demonstrate where congruence and incongruence exists between the organizational and environmental design strategies as well as with the existing regulatory framework. The significance of this study is in what it can demonstrate about the potential for the design of the built environment to contribute to the organizational goals of a nursing home provider who is seeking to implement and sustain PCC. In addition, knowledge about how organizational design must adapt to achieve PCC goals while still meeting regulatory guidelines it of critical importance.

2. Conceptual Framework

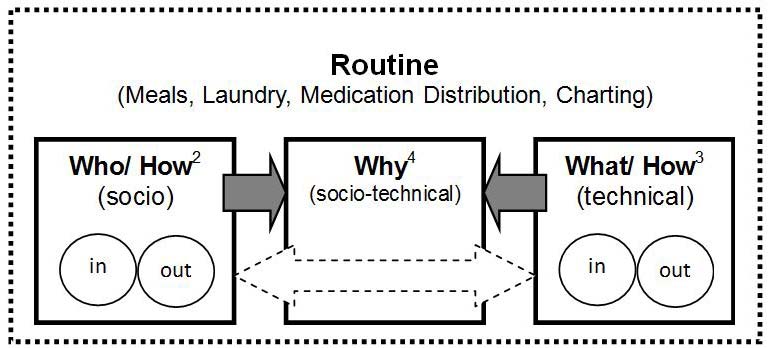

In order to explore the variables associated with environmental and organizational design, Weisman’s Model of Place (2001) and Rapoport’s socio-physical systems (1980a) are used as a framework for applying socio-technical theory of work and organizational management (Weisboard, 2004; Burke, 2011). This theory outlines the interactions that occur between people (social system) and the tools and techniques (technical system) of the HH (See Figure 2).

The “socio” aspect of the socio-technical system is made up of the individuals and groups who are responsible for the routines that make up the delivery of care. In order to understand how PCC is delivered, the organization is looked at across the entire domain and includes both staff in and out of the HH. It was predicted that routines require multiple participants, and the HHs would have a “nested” relationship within the larger organization. The “how” is the organizational strategy for the arrangement of these individuals as well as the manner in which their roles may be assigned (organizational design). Analyzing how individuals and groups participate in activity systems (such as routines) can provide insight into the role of the environment and the meanings that are assigned to the work and the setting (Rapoport, 1980b, p.10)

The “technical” aspect of the socio-technical system is made up of the environmental features (e.g. buildings, furnishings, equipment) that are used in the enactment of the routines (Weisman, 2001). These include HH features and the environmental supports provided by the larger environmental milieu. Environments can be conceptualized as settings that provide cues for behavior and which need to be decoded in order to be understood (Rapoport, 1980a, p. 286). The indicators sought through this framework are tractable artifacts that can be provided through observation of the environment, its contents as well as the behaviors that are enacted within the spaces where staff work. The “how” is associated with the arrangement of these spaces in relationship to one another both in and out of the HH.

The socio-technical structures identified here are focused on four highly regulated routines; meal, laundry, medication distribution, and charting. The goal was to understand two key relationships; first, the systemic structure of the key interrelationships between the people who work in the HH and those who support the HH from other parts of the larger organization, and second, the settings and other resources used to influence the routines over times (Senge, 2006). The “why” brings together the people and the environment, and, the organizational values that are operating with the “rules” that have been prescribed in order to create a “place” (Weisman, 2001; Morgan, 1997). This is a dynamic exchange because the design of the organization (socio) and the design of the environment (technical) have been driven by these values, rules, and policies (Morgan, 1997, p. 147). This framework provides an opportunity to evaluate if the meaning of place in these new HHs is different than traditional models of skilled nursing care.

3. Method

A case study methodology was applied for this inquiry based on recognized processes in qualitative research (e.g. Burawoy, 1998; Creswell, 1994; Clarke, 2009; Yin, 1984). The case study approach is especially relevant for investigating complex settings, such as nursing homes, as it allows for the collection of multiple sources of evidence in an actual situation or context (Haraway, 1991; Clarke, 2009; Stake, 2000). The setting is presumed to be ecologically-valid where no control efforts were employed. A qualitative research design using mixed-methods strategy was employed that included (1) ethnographic tactics of participant observation and open-ended staff interviews; (2) structured interviews with administrative personnel; (3) archival search and schematic articulation of the setting; and (4) photo-documentation of the composition of the HH features, spaces, and equipment that were integral in four routines. Using a mixed method approach allowed for triangulation of the analysis in the data collected.

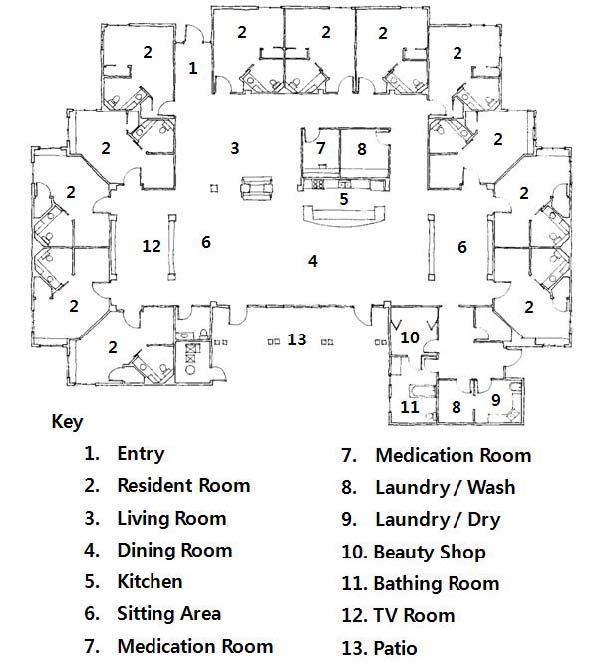

The site for this project, “Park Home” (pseudo name) is a long-term care facility located in the mid-western United States. This organization has built a pair of new freestanding skilled nursing buildings that fit Grant and Norton’s (2003) definition of the household model; an architecturally distinct space composed of “self-contained” living areas with 25 or fewer residents who (collectively) have their own full kitchen, living room, and dining room (See Figure 3). Each HH is approximately 8,500 square feet and accommodates 12 residents.

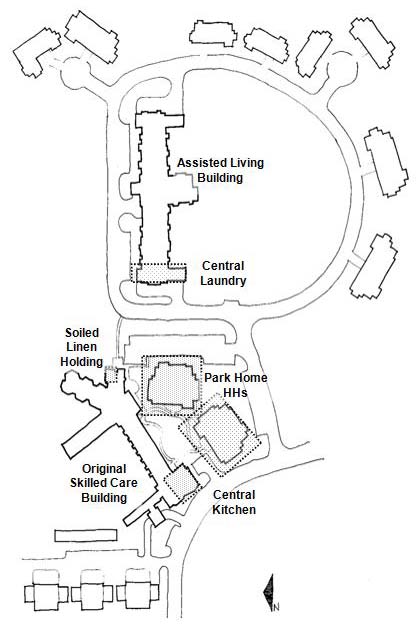

Park Home is a not-for-profit church related organization. Their campus provides three basic levels of housing and care services. There are currently 79 licensed skilled care beds for long-term stay residents, a congregate building that provide 40 apartments as well as assisted living services, and 16 duplex units plus one patio home for independent living. Skilled nursing care services are provided in two settings; the original skilled care facility that resembles a more traditional medical setting, and the two new Park Home HHs that are in close proximity to the original (traditionally designed) skilled nursing building. The original building also provides other central facility services. The public can access the HHs from the street, and there is a shared courtyard between the HHs and the original skilled care building. (See Figure 4).

4. Results

The delivery of the four identify routines (meals, laundry, medication distribution, and charting) are presented based on observed and reported actions of staff within and outside of the HH. Examples of key organizational and environmental attributes are identified and discussed as they relate to the congruence or incongruence between the design of the HHs and the organizational goals. Implications for regulatory compliance are also noted.

Meals.

Food service in the Park Home HHs is a combination of meals prepared in the HH kitchen and meals that are prepared in the Central Kitchen and then transported to the HHs. Food supplies for all of the skilled care facilities are received at the loading dock at the Central Kitchen. Bulk supplies are stored in the Central Kitchen until they are need either for meal preparation, or some supplies are later transferred to the pantry storage in the HHs. Breakfast foods are an example of items that are stored in larger quantities in the HHs. Many breakfast entrées are freshly prepared every morning in the HHs kitchen at flexible times by the homemaker (who is a member of the care staff). Residents may request their breakfast meal when they wake up in the morning and they have many options to choose from. The presence of the kitchen and the storage available for the necessary food supplies is an example of congruence with the organization’s goals for PCC and the environmental design of the HH.

Although the HH kitchen is equipped with built-in appliances suitable for cooking these foods, a counter-top griddle is used because the kitchen is not equipped with the necessary exhaust hood system over the cooktop required by the state fire marshal to permit the use of the cooktop. This demonstrates a lack of congruence with the environmental design and organizational goals for preparing food in the households. For this reason, lunch and dinner meals are not prepared in the HH kitchens. These meals are prepared in the Central Kitchen (by the Central Kitchen staff) and then transported to the HHs in heated carts (by the HH care staff). This requires that meal times are fixed with set menus, providing less choice and flexibility for residents. This demonstrates a lack of congruence between the organization’s goals and the design of the environment.

Laundry.

Laundry in the Park Home HHs is handled in two separate processes. The first process is for residents’ personal clothing, napkins, and aprons from the HH dining room. The second process is for bulk linens (sheets and towels). Each of these processes requires its own equipment, and policies and procedures. Personal clothing, napkins, and aprons are laundered with small scale residential equipment in the HH. Each resident has a personal laundry basket in his or her room and staff monitor the baskets and launder items regularly. A resident’s clothing is not washed together with another resident’s items. Because the care staff on the HH have now been cross-trained to perform this routine and the equipment is accessible to them, resident’s personal items are treated more carefully and are less likely to be miss-placed This is an example of congruence with the organizational design of the team and the environmental design of the HH.

Bulk linens are laundered in commercial equipment in the Central Laundry located in the Assisted Living building. This requires that staff from outside the household participate in the routine of laundry. There is space in the HH Laundry room for bins to hold soiled linens, and this is an important spatial characteristic to keep odors from permeating the HH. Care staff from the HH transport these bins to a holding room in the original skilled care building. From here, staff in Environmental Services transfers all campus laundry to the Central Laundry Room. Environmental Services staff return clean linens to the individual HHs.

Medication Distribution.

Medications and medical supplies are regularly delivered to Park Homes from a local pharmacy. Prescription items for the HHs are pre-sorted so separate deliveries are made to the HHs and the main skilled care building. Authorized clinical staff are required to check-in medications. These items are then secured in the Medication Room in the HH until they can be sorted and put away. Each resident’s medication is delivered to them personally in their own room at individualized times. The care staff in the HHs do not use medical carts to store and deliver medications in group settings.

Because there are Medication Rooms located in each of the HHs, it is easy for staff to manage this receipt, storage and dispensing process. The small scale of the HH makes it convenient for staff to deliver medication in a more personalized manner. This is an example of congruence between the goals of the organization for PCC and the design of the HH environment.

Charting.

Recording of daily information about resident health is handled by all members of the care staff in the HH. The HH design has incorporated a standardized electronic charting system that is networked to the central medical records office at Park Homes. In addition to electronic entries, physical charts on each resident are also maintained. Each form of record keeping requires specifically designated spaces within the HH for maintenance of privacy and security required by regulations.

Two (mounted) electronic charts are located on opposite sides of the HH. Staff must sign in with a unique identifier to use them, and, the system is design so it can only be read from a 90 degree angle. When the system is not in use the screens go black. Physical charts are located in the secured Medication Room within the HH. The small scale of the HH makes it convenient for care staff to take charts to other parts of the HH to work, and then, return the charts to the secured space.

Summary of Organizational Staff Roles.

As highlighted in the examples, staff must participate in multiple roles within the HH in order to achieve the goals of PCC. This requires that care staff have cross-training in multiple routines, and be willing to participate spontaneously in these routines as required to meet resident needs. For clinically trained personnel, this change to the organizational design (from previous hierarchical staff models) was reported to be initially challenging to their perceptions of quality care. These staff noted, however, that once the routines were in place, the benefits to the residents were obvious, and they appreciated how this new approach worked. It was also observed that staff assigned to the HH as well as staff outside the HH were integral in many of the routines that support the daily care needs. This was especially true for the routines of meals and laundry (See Table 1). Some HH models are described as “totally self-contained” with all routines managed within the HH. This case study revealed that totally autonomy is not probable within the regulatory guidelines that stipulate procedures for food and laundry services.

A “New” Place Experience for Skilled Nursing Care.

Through the interviews with care staff, it was observed that the Park Home HHs appeared to set a different tone for the expectations of work amongst those on the HH team. One staff member stated it as a…“difference in choice, the way it (the building) looks impacts the way people behave. My mood is different working here than there (in the main building).” Another staff member noted… “the households are more personal, we know the residents and they know us. There are all interested in us. Staff over there (in the main building) are dealing with so many people, it’s just a “job” over there.”

As part of the organizational goals in person-centered care, staff members’ also saw both a positive and negative impact of the detached HH setting on residents. Positive perceptions centered on the benefit of the homelike features and the ability of residents to more easily manage the sensory environment [primarily the amount of visual and auditory stimulation]. Staff members at all levels often commented that residents were able to maintain autonomy and competence far longer than if they were living in a more traditional (nursing home) arrangements. One staff member who worked outside of the HH observed…“Sick people seem to bounce back faster over there (in the HH). Something about the atmosphere seems to make a difference.” Another HH staff member noted…“One of our residents was over there (in the main building), she just walked the hallways crying out for people. She does good over here (in the HH), very content.” When pressed to identify what about the HH setting made such a difference, their answers were quite general and speculative, along the lines of, “…oh, I don’t know exactly, it’s smaller and it just feels more like home.”

4. Conclusion

Based on the evidences in this case study, it is proposed that the Park Home HHs creates a new set of patterns of behaviors and place experiences even though the rules for the routines of work are regulated under the same guidelines as in the traditional skill care building. This suggest that the socio-physical form of the HHs is not viewed within the same constructs of meaning as a nursing home. The implications of the findings can be considered at two levels; first what does this individual case study reveal about the general practices and policies of long term care; and second, how can the methods used to study these practices serve to complement and interface with other research being conducted. New organizational models of health care services, including HH models, will need to be understood at multiple levels. Theories on organizational development assert that a group’s behavior changes with the conditions operating in and upon it (Weisbord, 2004). The role of the built environment and the organizational structures supporting integrated HH teams will become increasingly critical as the demands for quality, both in care as well as the experiences of everyday life, continue to grow from consumer groups. It was observed, however, that the stated expectations for PCC don’t always fit the realities of the HH due to limitations in the environmental features provided. The effectiveness of a HH routine results from a congruence between the social and technical systems. There are also implications for congruence between regulatory policies and organizational and environmental design. Many of the rules that govern skilled care were developed around a medical-model approach. New operational policies may need to be considered in order to support PCC goals and outcomes.

Case study research has inherent limitations in generalizability to other settings. The exploratory nature of the study and the small sample does limit some of the conclusions that can be drawn in regard to the environmental solutions and staffing patterns that are used to comply with regulations in a HH model. One of the priorities in the methodology was to develop tactics that could be easily repeatable with research tools that would collect consistent information. Repeating these procedures in future studies will allow for a larger collection of case studies to be included for comparing and contrasting HH patterns.

This work is not intended to produce predictive theory that suggests a formulaic solution to the desired outcomes. This inquiry has been problem-focused and consistent with the pragmatic perspective (e.g. Fishman, 1999; Flyvberg, 2001). Attempting to join agency and structure, people and practices have been explored in relationship to the everyday work of those doing a job in a setting that is guided by rules. The purpose of this study is to produce new understanding of how some HHs are currently functioning as well as provide knowledge that can facilitate desired regulatory change. The individual case study may be only an isolated example, but these HHs operate successfully within the context of the larger “long-term care system” therefore, they are a reflection of this system (e.g. Burawoy, 1991, p. 281). Studying the setting and observing those who do the work provides a picture of the environmental features that support (or don’t support) these rules as well as the expected functions of a skilled care setting.

The ultimate purpose of long-term care is to benefit those individuals who rely on these places and services for extended periods of time. Robert Kane (2005), states, “even if we do not yet know how to systematically produce better quality of life, we need to recognize it when it occurs and continue to toil for actions that can foster it” (p 14). Nursing homes and what they are meant to accomplish are defined by a “philosophy” or a “model of care” and are understood by the set of goals that are realized organizationally, socially, and architecturally (Weisman, Chaudhury, Diaz Moore, 2000, p. 13).

Design professionals can be partners in creating settings that support quality of life if they have a better idea of those “evidences” that are important to PCC outcomes. This case study reinforces the importance of recognizing the role the environment plays in these policy issues (e.g. Kane, 2005, p. 2). This case study also provide evidence that it is no longer acceptable to make assumptions about practices that may not be practical in HHs without the proper environmental and organizational supports. The routines may have the same purpose, but the nature of work has changed, and therefore our assumptions about this work as well as the environments must also change. This framework of investigation can be adopted to escape the conventions of the hidden program (Silverstein & Jacobson, 1985) of nursing home design, and these strategies can also be applied to reconsider how research is used to inform the design of this new emerging place-type.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Association of Health Care Interior Designers (AAHID), the Interior Design Educators Council Foundation Carol Price Shanis Award, and the Rothschild Foundation.

Notes

Copyright : This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted educational and non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

-

Arling, G., Kane, R. L., Mueller, C., Bershadsky, J., & Degenholtz, H. B. (2007). Nursing effort and quality of care for nursing home residents. The Gerontologist, 47(5), 672-682.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/47.5.672]

- Burawoy, M. (1991). Ethnography unbound: Power and resistance in the modern metropolis. Univ of California Press.

- Burawoy, M. (March, 1998). The extended case method. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4-33.

- Burke, W. W. (2011). Organizational change: Theory and practice, Third Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-related Statistics. (March, 2008). Older Americans 2008: Key Indicators of Well-being. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office.

- Fishman, D. B. (1999). The case for pragmatic psychology. New York: New York University Press.

-

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How it can Succeed Again. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511810503]

- Grant, L. A., & Norton, L. (2003, November). A stage model of culture change in nursing facilities. In Presentation to the 56th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America.

- Haber, C., & Gratton, B. (1993). Old age and the search for security: An American social history. Indiana University Press.

-

Haraway, D. (1991). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. In D. Haraway (Ed.) Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066]

-

Hovey, W. (2000). The worst of both worlds: Nursing home regulation in the United States. Review of Policy Research, 17(4), 43-59.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2000.tb00956.x]

-

Kane, R. A., Lum, T. Y., Cutler, L. J., Degenholtz, H. B., & Yu, T. C. (2007). Resident Outcomes in Small-House Nursing Homes: A Longitudinal Evaluation of the Initial Green House Program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(6), 832-839.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01169.x]

-

Kane, R. L. (2005). Changing the face of long-term care. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 17(4), 1-18.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/J031v17n04_01]

- Lustbader, W. (2001). The pioneer challenge: A radical change in the culture of nursing homes. In Noelker, L. S., & Harel, Z. (Eds.) Linking quality of long-term care and quality of life. New York: Springer.

-

Meyer, S. (2006). Role of the social worker in old versus new culture in nursing homes. Social Work, 51(3), 273-277.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/51.3.273]

- Morgan, G. (1997). Images of organizations. London: Sage Publications.

- Morse, J. M., Stern, P. N., Corbin, J., Bowers, B., Clarke, A. E., & Charmaz, K. (2009). Developing grounded theory: The second generation (developing qualitative inquiry).

-

Pekkarinen, L., Sinervo, T., Perälä, M. L., & Elovainio, M. (2004). Work stressors and the quality of life in long-term care units. The Gerontologist, 44(5), 633-643.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.5.633]

-

Rabig, J., Thomas, W., Kane, R. A., Cutler, L. J., & McAlilly, S. (2006). Radical redesign of nursing homes: Applying the Green House concept in Tupelo, Mississippi. The Gerontologist, 46(4), 533-539.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.4.533]

-

Rantz, M. J., Hicks, L., Grando, V., Petroski, G. F., Madsen, R. W., Mehr, D. R., ... & Bostick, J. (2004). Nursing home quality, cost, staffing, and staff mix. The Gerontologist, 44(1), 24-38.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.1.24]

-

Rapoport, A. (1980a). Cross-cultural aspects of environmental design. In I. Altman, A. Rapoport & J. Wohlwill (Eds.), Environment and culture. New York: Plenum.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0451-5_2]

- Rapoport, A. (1980). Vernacular architecture and cultural determinants of form. In A. King (Ed.). Buildings and society: Essays on the social development of the built environment. London: Routledge.

-

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4170300510]

- Silverstein, M., & Jacobson, M. (1985). Restructuring the hidden program: Toward an architecture of social change. Programming the Built Environment, Preiser, WFE (ed), Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York: Van Nostrand.

- Stake, R. E. (2000). Case studies. In N.K. Denzin., & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.). Handbook of qualitative research, pp. 435-454. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Talerico, K. A., O'Brien, J. A., & Swafford, K. L. (2003). Person-centered care. An important approach for 21st century health care. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 41(11), 12-16.

-

Vladeck, B. C. (2003). Unloving care revisited: The persistence of culture. Journal of Social Work in Long-Term Care, 2(1-2), 1-9.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/J181v02n01_01]

- Weisbord, M. R. (2004). Productive workplaces revisited: Dignity, meaning, and community in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons.

- Weisman, G. D. (2001). The place of people in architectural design. The architect's portable design handbook: A guide to best practice, 158-170. New York: Mcgraw Hill.

- Weisman, G. D., Chaudhury, H., & Moore, K. D. (2000). Theory and practice of place: Toward an integrative model. The many dimensions of aging, 3-21. NY: Springer.

- Yin, R. (1984). Case Study Research: Design and Method. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.