Analysing Intersubjective Relations in Collaborative Design Ideation Process

Abstract

Background Despite the social nature of collaborative design, the collaborative design process has not been sufficiently researched as a social action. Intersubjectivity, which concerns the relations between various perspectives of two or more people, can serve as a useful framework for understanding the complex process of collaborative design and proposing effective communication methods to achieve the common goal of designers.

Methods This study aims to analyse the process of achieving mutual understanding and a common ground during a collaborative design process, utilising the concept of intersubjectivity. The earlier meetings for the ideation of two teams of three designers each were observed, and the conversations were analysed. The analysis mainly focused on their levels of perspective and meaning generation.

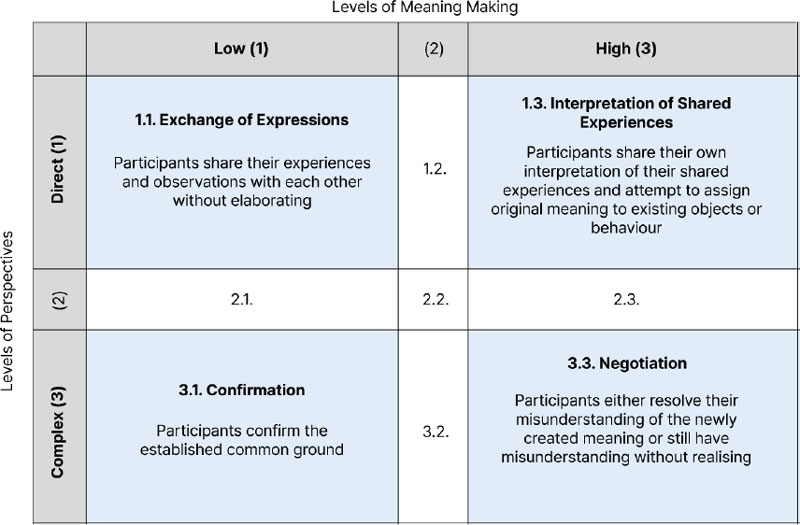

Results A matrix was developed based on the levels of the two variables, and each conversation was categorised according to the evaluation of these variables. To summarise, four key categories emerged: 1.1 Exchange of Expressions, 1.3 Interpretation of Shared Experiences, 3.1 Confirmation, and 3.3 Negotiation. When a conversation exhibited a lower level of meaning-making and a higher level of diverse perspectives, participants typically confirmed the established common ground. In contrast, when there was a high level of meaning-making and complex interactions among perspectives, participants either resolved their misunderstandings about the newly created meaning or remained in a state of misunderstanding without realising it.

Conclusions This analysis leads to the conclusion that the complex and critical conversations, which significantly impacted on the outcome, were a result of the cumulative effects of ‘simpler’ conversations that scored low on both variables. Throughout the meeting process, the regeneration of meaning and establishment of common ground were achieved.

Keywords:

Intersubjectivity, Design Ideation, Collaborative Design, Design Ideation, Common Ground1. Introduction

This study aims to analyse the process of achieving mutual understanding and collaborative ideation during a collaborative design based on the intersubjectivity. Intersubjectivity refers to ‘the process of achieving mutual understanding and common ground between two or more subjects’ (Berk & Winsler, 1995). Design is a process of seeking solutions for a problem that the participants agreed on. Therefore, intersubjectivity plays a fundamental role for negotiating different perspectives into an agreed and shared understanding of the problem or other matters. Therefore, the design process is an ideation process involving various intersubjective relations between designers, and understanding the process with the concept of intersubjectivity can enhance the process of successful ideation. Also, language in the collaborative design process plays a role as a representational facilitator in the design performance (Dong, 2006). Designers who are social animals and various social interactions including language involved in the design process can be observed from sociological, social psychological and socio-material perspectives (Matthews et al. 2021). This study aims to systematically investigate the process of achieving common ground among designers. It includes the analysis of interactions occurring within the collaborative design process.

Collaborative design refers to the process in which actors from different disciplines share their knowledge about the design process and content. The aim is to create shared understanding on both aspects, to integrate and explore their knowledge and to achieve the larger common objective: the new product to be designed (Kleinsmann, 2006). “Collaborative applications are intended to support the work performed by a group of collaborators who pursue a common goal” (Messeguer et al., 2009, p.565) and is a critical component of many social actions involving more than one individual. In collaborative design or any other social process, the actors (designers) are required to develop a shared understanding and establish common ground. Common ground refers to “the set of assumptions mutually accepted by the discourse participants and treated as true” (Haselow, 2012, p. 189). In the context of collaborative design, common ground can be understood as the shared knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions among individuals involved in the design process (Clark, 1996). Developing common ground among designers is essential as it helps establish a shared understanding of the design problem and enables stakeholders to work collaboratively towards developing effective design solutions (Mao et al., 2018).

The importance of common ground and shared understanding in collaborative design has been recognised. Mao et al. (2018) and Sengupta and Jeeva (2017) argue that collaborative design requires designers to establish common ground and a shared understanding of the design problem and processes to develop practical design solutions and negotiate conflicting viewpoints. Also, Pifarre and Staarman (2011) emphasised the reciprocal understanding, stating that “it thus seems crucial that the social interaction is focused on the ideas of the participants and that the participants are not only willing to share these ideas, but do so in a respectful and open-minded manner” (p. 3). Kleinsmann and Valkenburg (2008) explain the role of shared understanding in the co-design products by highlighting the findings of several early studies. The high quality of the final product is reduced by a lack of shared understanding because not all problems are addressed and discussed for solutions (Song et al. 2013), and lack of shared understanding can cause unnecessary iterative loops (Valkenburg and Dorst, 1998).

This study aims to present the findings of the analysis of the process of designers developing common ground through the lens of intersubjectivity – including building common ground, third-turn repair, and levels of perspectives. The study will focus on the linguistic and intersubjective elements that contribute to forming and maintaining of common ground. By identifying these elements, this study provides insights into how designers interact and collaborate, leading to a better understanding of the collaborative design process. The importance of this study lies in its potential to contribute to the existing body of knowledge on collaborative design. While there have been studies on the importance of common ground in collaborative design, there is still a lack of understanding of how designers develop common ground through interaction. By analysing the interaction occurring within the collaborative design process, this study can provide a more detailed understanding of developing common ground. Moreover, the outcomes of this study will aid in the practical generation and negotiation of design ideas, ultimately facilitating the attainment of a finalised design concept.

2. Literature Review

2. 1. Intersubjectivity and Common Ground

Intersubjectivity describes interactions between individuals’ various forms of perspectives and is defined in diverse ways within the social sciences. It encompasses agreement on the meanings assigned to objects, understanding of agreement or disagreement of opinions, and various relationships between individuals’ perspectives (Gillespie & Cornish, 2009). Table 1 below illustrates the three levels of perspectives.

The goal of collaborative design is the formation and integration of knowledge (Kleinsmann & Valkenburg, 2008, p. 371). Mutual understanding refers to forming an accurate meta-perspective through dialogue between individuals (Corti & Gillespie, 2016), which means correctly understanding the interlocutor’s perspective. Meta-perspective involves establishing a common ground within the context of interaction rather than adhering strictly to agreed-upon points (Corti & Gillespie, 2016). In the design performance situation, conversations involve many implicit and nonverbal communications, making it difficult to establish a common ground for intersubjectivity, sometimes leading to misunderstandings. As Table 1 suggests, to achieve the goal of collaborative design, not only agreeing on the direct perspectives but understanding and accepting the self and other’s meta- and meta-metaperspectives are also crucial. Subjectivity refers to a self’s particular perspective on the matter (x), and the other’s perspective on the particularity of the self and other. Therefore, the accumulation of interactions of perspectives and complexity does not create the objectivity of the matter. However, the depth of subjectivity, the increased interactions between different levels of perspective reveals the uniqueness of the collaborative design ideation process.

A third-turn repair occurs when conversation parties address problems in speaking, hearing, or understanding of the talk (Shegloff, 1997). Third turn repair can be initiated by the ‘other’ or the ‘self’. In a third turn repair, a speaker in a conversation makes a statement (turn 1), to which the subsequent response exposes an apparent misunderstanding (turn 2). The misunderstood speaker then attempts to clarify the issue in the turn following the one where the misunderstanding was evident (turn 3) (Shegloff, 1997). Third-turn repair repairs detected misunderstandings or disagreements as the speakers express their understanding verbally. Dingemanse et al. (2015) discovered the universality of the language system of repair that is the language use are primarily similar across cultural groups, stating that third-turn repairs occur across different cultures. However, the studies around third-turn repair in Korean language are limited to English as a Foreign Language (EFL) education. This study attempts to analyse the third-turn repair occurring in collaborative design conversation.

2. 2. Collaborative Design

Oak (2010) examined how the dialogic elements in design can be understood from a micro-sociological and socio-psychological perspective of symbolic interactionism. Symbolic interactionism is a theoretical framework proposed by George H. Mead (1934) which suggests that individuals act based on the meanings they attribute to objects, and past interactions and experiences form these meanings, thus individuals may assign different meanings to the same object. Oak’s research shows the characteristics of collaborative, contextually specific, and discursive design processes. Oak further argues that reflecting on dialogic attitude can allow designers and design educators to view them from a new perspective. Kleinsmann and Valkenburg’s (2008) study is based on cases of design projects conducted by designers and colleagues from other fields, which showed that individuals assign different meanings to the same object, and they claim that oral communication is more effective than written communication to integrate these meanings. The integration of meanings of objects affects not only the interaction between actors in the project but also project management and corporate organisation. In addition, in a study by Ge, Leifer & Shui (2018) on the developmental role of situated emotions in collaborative design, a significant positive correlation was found between the use of intonation and new words and the measured emotions through nonverbal communication and skin conductance, which emphasises the importance of designers’ emotions and gut feelings in the design process, which were difficult to find in previous studies. Thus, the importance of environmental or socio-psychological factors in the design studio, which were often taken for granted or not studied in the past, is increasingly emphasised, and this study also examines the social interaction among designers and their understanding of it in the collaborative design process.

Intersubjectivity touches upon various research areas but studies around intersubjectivity in creative and generative conversations still need to be completed. This study focuses on identifying patterns of intersubjective relations created during collaborative design by analysing conversations between designers.

3. Method

3. 1. Experiment design

To understand the process of developing common ground among designers in the collaborative design process, the participants were given a design task - to design a chair for people in traditional markets of Korea - and their first meetings were recorded and observed. The meetings took place in a seminar room within the university they attend. They sat around a table and each participant was facing a camera recording them to avoid blind spots and ensure all three participants’ voices were recorded. The first meetings, which took place right after they visited the chosen markets, were observed for analysis for the following reasons. The first meeting involved the most exchanges and sharing of their experiences at the places, participants visited the places together however their experiences and specific elements that they have significantly observed varied. Therefore, we agreed that the first meeting was one of the most affluent and important processes, and the most meaningful ideas could be generated and negotiated as they actively discussed their own experiences and thoughts with other team members. The design tasks were performed over one semester as a part of a course at a design class in their undergraduate course.

The participants consisted of six third-year students, divided into two teams. All six participants were third-year female university students studying industrial design in Seoul, South Korea. The participants had already conducted research on a similar task in their classes and had prior knowledge and understanding of the subject - the markets, and the process.

Team A was given Noryangjin Fisheries Wholesale Market (노량진 수산물 도매시장), one of the largest fish markets in Seoul. The market is a mix of wholesale and retail stores for regular customers. It is known for its lively atmosphere and fish auctions - the prices of products are decided according to the quantity of products (KTO, 2023). Team B was given Dongmyo flea market, famous vintage market in Seoul that holds a historical significance and embodies the 1960s and 70s atmosphere. The market sells various products varying from clothing to electronics (Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2021). Both team members had conducted field research prior to the meeting and had taken photos and videos taken from each market. The visual data was used as the starting point of discussions.

The meeting was video, and audio recorded in the absence of researchers at the design studio. The cameras were placed in front of each participant. After the participants had finished with their meetings, the researchers interviewed them and reviewed the meeting processes.

3. 2. Analysis

The entire conversations from both teams were divided into the smaller conversations and coded into semantic units based on the contents discussed, and each section was evaluated in terms of their complexity in (1) perspective interactions and (2) level of meaning-making – the level of interpretations. A 3-point Likert scale was used for both evaluations. Adopting a 3-point Likert scale stemmed from its alignment with three distinct levels of perspective: the direct perspective, the meta-perspective, and the meta-meta perspective. The analysis involved three researchers, with the inclusion of a third researcher, intended to introduce a fresh perspective to the analysis. The leading researchers were the authors of the paper, and the third researcher was a master’s student who had graduated from the same course as the study participants and is currently working with the authors. Every interaction among participants’ perspectives was analysed and classified into either direct perspective, meta-perspective, and meta-meta perspective. The different levels of perspective were explained and discussed prior to the analysis to ensure that the researcher analysed conversations in a consistent manner. Then, the interactions in a conversation unit were assessed for their complexity and assigned a number between 1 and 3, with three being the most complex, indicating where it involves meta and meta-meta perspectives. When the evaluations between participants differed, all three researchers discussed the reasoning behind their judgment and resolved the differences in views.

The main and sub-keywords from each conversation unit were drawn, and the researchers determined and discussed the levels of meaning-making. The levels also varied between 1 and 3, with 3 being the highest meaning-making level.

3. 3. Procedure and result

The conversation analysis reveals the general conversation atmosphere in the design process. This research analysis examines the level and meaning generation of these everyday design conversations. In judgment and analysis, three judges attempted to assess and analyze the relationship between subtle and symbolic meaning changes and mutual subjectivity in the participants’ conversations.

As a result of the experiment, transcripts totaling 228 minutes of meetings and six pages of sketches from two teams were obtained. The analysis of this study was based on the conversations during the initial idea formation phase, where the focus was on participants sharing and understanding each other’s perspectives and forming mutual understanding. Team A’s conversation lasted for 1 hour, 49 minutes, and 57 seconds, with 1,252 turns. The whole conversation was divided into different conversational parts based on the contents, and Team A’s conversation was divided into 134 parts. Team B’s conversation lasted for 1 hour, 59 minutes, and 37 seconds, with 1,196 turns. The conversation was divided into 118 parts. Irrelevant conversations such as conversations during breaks and participants discussing irrelevant topics were excluded for evaluation.

4. Result

<Table 2> below illustrates the quantitative findings of the analysis. Conversations categorised as 1.1. Exchange of Expression were found to be predominantly occupying the conversations in both teams’ meeting. However, it was necessary to consider the remaining three quadrants, which constitute a minority proportion of conversation. Even though they did not dominate the conversation in terms of their quantity, but interesting and original ideas emerged from such conversations.

The following matrix was developed based on the analysis of the level of perspectives and meaning-making (Figure 1). The conversations were placed into the matrix according to the levels of perspectives and meaning making evaluated by three judges.

Three judges evaluated each team’s conversation, and the mode was used to determine where each conversation was placed in the matrix (Figure 1). Based on the characteristics of conversations placed in the quadrant, each quadrant was given a title.

- 1.1. Exchange of Expression – in conversations placed in 1.1., participants shared their experiences and observations other without elaborating.

- 1.3. Interpretation of Shared Knowledge – in 1.3, participants share their interpretation of the shared experiences and attempt (or do) assign their original meaning to the observed objects or behaviours.

- 3.1. Confirmation – in 3.1., participants confirm that they have achieved common ground by demonstrating their understanding.

- 3.3. Negotiation – in 3.3., where the conversations are the most complex and generate new meaning, participants either resolve their misunderstanding of the newly generated meaning or continue to have misunderstandings and/or disagreements without noticing.

Each category will be explained with relevant examples below.

Most of both team’s conversation fell into the 1.1 Expression, where both perspective and meaning-making level were low. Followed by 1.1 Expression, conversations in 2.2 (which had moderate complexity and generated new meanings but relatively insignificant - scoring 2 for both variables) were observed most frequently. The conversations that had scored 2 for either level was excluded for further analysis due to their ambiguity and uncertainty of evaluation. Conversations in 3.3. Negotiation occurred relatively less frequently (once in both teams), suggesting that conversations that involved complex dynamics between perspectives and had meaningful and unique interpretations were difficult to achieve in the beginning stages of collaborative design.

While Team A’s conversation was divided into more than 130 different conversation units, Team B’s meeting only was divided into 70 different conversation units, although the length of the meeting was relatively similar. The researchers agreed that Team B’s conversations were relatively simpler in their levels of perspective and meaning-making, as their key concept was agreed upon among the participants of Team B at an earlier stage of the meeting. This may be due to the differences in team compositions and personal differences, as the approach that each team took may vary. However, the process of sharing lower-level conversation and developing further to re-generate new meanings were observed in a similar pattern. In addition, Team B’s conversations were more about confirming their idea generated at the beginning of the meeting rather than generating and exploring alternatives. The analysis based on the matrix mainly focused on Team A’s conversations due to the more complex and dynamic structures of different conversations.

4. 1. Exchange of Expressions (1.1)

The conversation in 1.1 Exchange of Expression were evaluated lower on both levels of meaning-making and interaction of perspectives and they shared their direct observations of the market with each other. The process of sharing and discussing their direct observations had built the foundation for achieving common ground.

All participants are sharing what they observed from the market with each other in this conversation. In line 531, B described how they felt about the auction site by stating that the way people were standing in different levels looked like staircases. Then C and A, added their own observations to B’s earlier statement. The direct perspectives were observed in this conversation

4. 2. Interpretation (1.3.)

In the high-level meaning-making conversations, common ground was built among the participants. Their interpretations of the experiences and the matters became unique meanings to the process of idea development. In the following excerpt of conversation 89 of Team A, the fish tank in a truck became a stroller for the fish.

C first mentions the ‘portable fish tank’ while looking at the photographs taken from the visit (line 795). Then B changes the mentioned object from ‘fish tank’ to a new object: ‘transportation’, by giving a new interpretation (line 796). Then the ‘transportation’ becomes ‘transportation for fish’ by C again, followed by A’s new addition of meaning, and it becomes a ‘stroller.’ Finally, A combines the idea of a ‘stroller’ and the fish onboard; the ‘portable fish tank’ from line 795 becomes a ‘stroller for fish’. This process involved the direct perspectives of the participants, but the objects were constantly changing as they were giving a new meaning to the previously created ideas.

Another example of 1.3. Interpretation below demonstrates how one new interpretation can generate relevant, but new meanings and eventually lead to a larger-scale shift. In the following excerpt, B compares the auctioneer to a performer at a concert, followed by more similes mentioned, and finally the auction site becomes a DJ concert.

These interpretations of different components of the auction site originated from B’s first use of auctions and DJ booth similes (line 284), and the other participants were able to elaborate on it. The conversation where this simile was first mentioned, where the meaning-making level was high, held a significant role in the meeting itself, and had a crucial impact on the outcome.

Conversation describing what the participants have directly observed from the market (line 284-286) developed into a re-interpretation of the auction site (line 287-282). The participants had shared experiences of the market. The process of revisiting them verbally and sharing their direct perspectives of the observations allowed them to develop further from the direct perspectives into higher level perspectives. The higher-level perspectives - the simile of auction site and a DJ concert, became a new common ground between participants.

<Table 6> summarises the similes and interpretations of the observed objects that were used in their final report and the ideas that emerged from conversation 35 of team A.

Based on the new interpretation of the auctions in the fish market, Team A rediscovered the space and stakeholders of the sites. They compared the auctions site to a DJ concert based on several critical similarities of the two places. The following section explains how the participants gave new meaning to the auction sites and their components.

1. Auctioneer → Rapper

The auctioneer leads the auction by speaking un-understandable (to outsiders) language. The auction went fast, and the participants who were not familiar with the fish market in general could not follow the auctions and what the auctioneer was saying. They interpreted the auctioneer as a rapper who raps fast in an addictive rhythm.

2. Speaker → Speaker

The speaker was one of the components that linked the auction site and a DJ concert. The sound was one of the main similarities between the two places.

3. Screen → Screen

The screen was another common component of both places; however, its functions may have varied to a certain extent. In an auction, the screen displays different prices of different products, but it also displays the current situations or displays visuals that enhance the concert experiences. However, the existence of visuals held the key role in the interpretation.

4. Assistant → DJ

An assistant handled the sound and screen at the auction site. The participants compared the assistant to a DJ who manages the sound system and the screen.

5. Groups of retailers → Concert crowd and 6. Retailers → Audience

The group of retailers gathered around the auction site was interpreted as the crowd at the concert. They gathered at a specific place at a certain time to serve different purposes, but they were both focused on the auctioneer or the rapper, and the sounds that they were producing. The participants also explained how the movements and sounds that the retailers were making were similar to those of the concert crowd, who enthusiastically watched the concert.

6. Trucks → Stages

Lastly, the trucks that move around the auction sites were compared to the stages that can be reassembled and moved around for different concerts.

Another example of 1.3. Interpretation from Team A demonstrates how the interactions of perspective can alter the general meaning of an object. In the following conversation, the participants’ retrospective perspectives on the research site (fish market) shifted from negative to positive experiences. Participant A states, “But it felt more beautiful. When I was inside, it was kind of scary (근데 아름다운 느낌이 좀 더 많이 들었어. 나는 안에 있을 때는 좀 무서운 느낌이 들었는데)", and C agrees by saying “Right, right (맞아 맞아)".

In this conversation, the ‘scary’ fish market shifted to ‘beautiful and passionate’. The participants actively shared their retrospective direct perspectives on the site but created new meaning beyond what they felt during the field research. The new common ground (the fish market is beautiful from upstairs) developed further as participants added their direct perspectives and detailed similes.

4. 3. Confirmation (3.1.)

The conversations fall into the 3.1. Confirmation tends to confirm the common ground that may (or may not) exist among all participants. A participant expresses their direct perspective on the matter (either at a lower or higher meaning-making level) and other participants add their direct perspectives to the expression. Participants confirmed or repaired the common ground in the conversation. Only one conversation had a low meaning making-level and complex interaction of perspectives (<Table 8> Conversation 70 of Team A).

This excerpt can be analysed by the third-turn repair which involves relatively complex interaction of perspectives. However not every conversation involving repair fell into the same category. Other- and self-initiated repair involves understanding the other’s perspective on the matter, as it can only occur when the speaker realises that the other is having either a misunderstanding or disagreement. In the excerpt from conversation 70 of team A, C attempts to explain the box that the sellers use in the retail area of the market but realises that the other participants need help understanding what they are trying to explain. C asking, “Do you know what I mean?” (“뭔지알아?”) suggests that while C was talking, C noticed that the participants may not have understood them, which demonstrates C’s meta-perspective - C’s perspective on A and B’s perspectives on the box that C was explaining. In line 648, A initiates repair as A explicitly communicates that they did not understand. The repair initiation followed by C’s repair, C uses alternative words and expressions to explain what they attempted to explain in line 647. Then, A asks, “By just putting hands in?” (“손만 넣어서?”), they confirm their understanding by adding their perspective onto C’s explanation. In this example, there were complex interactions between various levels of perspectives. However, as the participants were only discussing and repairing about an existing object (the box) and did not elaborate from there, this conversation fell into the 3.1. Confirmation. However, there were instances when repair took place while new meanings were being created. The following example demonstrates such instances.

The object discussed in this excerpt is the ‘yellow box’. C mentions the yellow box as the components to create a path in the market, but A, in line 740, asks back, “Components creating a path?” implying that they did not understand what C meant by “components creating a path.” Then C successfully repaired by adding the new keyword ‘alignment’ and used visual aids (sketches) to their explanation. Other-initiated repairs took place during this conversation while a new meaning was established - the yellow box became a component of a road, and the keyword ‘alignment’ was mentioned. This conversation and other examples of other- and self-initiated repairs were evaluated as moderate perspective interactions.

4. 4. Negotiation (3.3.)

On the other hand, there were some conversations involving both high meaning-making and higher levels of perspectives.

In conversation 135 of team 1, the participants’ meta- and meta metapersepectives are observed, as they were discussing what B refers to when they said ‘slanty (비스듬이)’. The concept of ‘slanty’ was created earlier in the meeting (#104) via talk and sketch, and the participants thought the common ground was built. However, as shown in conversation 136, they had different interpretations of ‘slanty’ in line 1227. They realised as they were sharing their direct and meta-perspectives. The meaning of ‘slanty’ was being recreated immediately, as they realised there was a misunderstanding. They repair their understandings of ‘slanty’, and other-initiated repair was observed in this conversation section. The higher meaning making level and higher level of perspective conversation (quadrant 4) often involves self- or other-initiated repairs as they may be misunderstandings or disagreements. The trouble source tends to draw conversations involving higher-level perspectives conversation, and higher-level perspective conversations often involve higher meaning-making as they are trying to negotiate the disagreement through active communication.

5. Discussion

5. 1. Accumulation of simpler conversations

Simpler conversations that did not mainly introduce new insights may appear less significant and pivotal compared to discussions at higher levels. However, the common ground upon which these conversations are based is cultivated throughout the meeting. In other words, the accumulation of lower-level discussions forms the foundation for the emergence of new meanings and ideas. For example, participants in both teams initially described their market experiences in straightforward terms but gradually incorporated metaphors and similes into their observations. Team A participants identified significant market elements, such as the auction site and fish tank, and infused their interpretations based on shared understanding. A similar trend was observed in Team B, where discussions began with direct observations of the market, leading to deeper levels of conversation by interpreting the observed features. Just as Team A employed metaphors and similes, Team B likened the opening and closure of the market to decoupage and montage. Both teams primarily focused on discussing their market observations initially—encounters with people and objects—before progressing to adding interpretations based on those discussions. This suggests that the accumulation and evolution of common ground through lower-level conversations lays the groundwork for subsequent discussions, whether at higher levels of meaning-making and complexity or not. The conversation in Team A differed from that in Team B regarding the extent of lower-level conversation, which facilitated a more profound and broader exploration of the design idea.

5. 2. Regeneration of Meaning and Establishment of Common Ground

As new meanings emerged, more minor nuances of meaning were subsequently regenerated based on the established characteristics, as shown in <Table 6>. When a new meaning surfaced (the auction site being likened to a concert by Group A), the objects and individuals within that context (auctioneer, sellers, screen, etc.) also transformed based on the established common ground (the notion of the auction site as a concert). In the conversation of Team A (<Table 5>), when the auction site was reimagined as a concert venue, the auctioneer assumed the role of a performing artist, and the truck morphed into a stage. This may propose that more superficial and smaller perspectives can merge to regenerate a larger perspective that can guide the designers to attain the design ideation outcome. Conversely, it was also able to observe some cascading changes in the understanding of more minor elements (stages, sellers, auctioneers, and boxes) that form the more significant and holistic idea (auction site, the opening and closing of the street markets), indicating that elements of common ground can interact and change when common grounds are successfully achieved without misunderstandings. This finding aligns with the findings of earlier studies on metaphors in conceptual designs, metaphors are employed in various areas of design, and that “metaphors allow designers to understand different concepts, enriching imagery and imbuing concepts with meaningful attributes” (Hey & Agogino, 2007, p.1).

Successful conversations like <Table 5> can occur when the common ground is established without misunderstanding or disagreement (or successfully repaired), underscoring once again the critical role of sharing lower-level conversations thoroughly. However, since every collaborative design involve different team compositions and individuals with varying approaches to work, the process can vary significantly.

6. Conclusion

This study explains the intersubjective relations in the early stages of collaborative design interactions. It emphasises the importance of active expressions of direct perspectives for idea generation and flexible meta-perspectives that can enhance the understanding of the other’s and their perspective. The conversations were categorised based on their levels of meaning making and interactions between perspectives. This analysis led to the conclusion that the complex and crucial conversations that had a certain amount of impact on the outcome negotiation were a result of the accumulation of all ‘simpler’ conversations, which had low scores on both variables. The 3.3. Negotiation conversations could not have occurred if the designers had not talked about their first-hand experiences and actively shared them with other team members. By sharing and discussing their own experiences and perspectives, the team was able to come up with unique interpretations and reassignments of meanings.

6. 1. Implications

The conclusion and discussion suggest that collaborative design should involve the active exchange of various levels of perspective in order to achieve common grounds between designers meaningfully. Each designer will have certain moments of new idea generation, and the interaction plays a key role in sharing them effectively and developing the idea further to design decisions with other designers’ contributions. Team B achieved common ground with the key word (decoupage and montage of each stall, generating a route within the market). On the other hand, Team A went through a longer process of sharing lower levels of perspectives to achieve this. The process can vary in lengths and complexity for various reasons, but how the misunderstood conversations are successfully repaired, and the common grounds are achieved will affect the efficiency of conversations.

6. 2. Limitations

This research faces a number of limitations due to its artificially set meeting environment. It is necessary to observe various forms of collaborative design by varying the relationships between designer participants and investigating different stages of collaborative design.

6. 3. Further studies

Future research needs to observe the actual collaborative design project meeting process conducted in cooperative settings to deeply investigate what roles do communication and intersubjectivity plays in a real-life design task. Secondly, the analysis could be improved by adopting a quantitative research method, such as analysing the auditory data and investigating their correlations with the qualitative characteristics of conversations.

Notes

Copyright : This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted educational and non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- Berk, L., & Winsler, A. (1995). Schaffolding Children's Learning: Vygotsky and Early Childhood Education. Washington DC: NAEYC.

-

Clark, H. H., & Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition, 22(1), 1-39.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(86)90010-7]

-

Corti, K., & Gillespie, A. (2016). Co-constructing intersubjectivity with artificial conversational agents: People are more likely to initiate repairs of misunderstandings with agents represented as human. Computers in Human Behaviour, 58, 431-442.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.039]

-

Dingemanse, M., Roberts, S. G., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Drew, P., Floyd, S., ... & Enfield, N. J. (2015). Universal principles in the repair of communication problems. PloS one, 10(9), e0136100.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136100]

-

Dong, A. (2007). The enactment of design through language. Design studies, 28(1), 5-21.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2006.07.001]

-

Ge, X., Leifer, L. J., & Shui, L. (2021). Situated emotion and its constructive role in collaborative design: A mixed-method study of experienced designers. Design Studies, 75.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2021.101020]

-

Gillespie, A., & Cornish, F. (2009). Intersubjectivity: Towards a Dialogical Analysis. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40(1), 19-46.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2009.00419.x]

-

Haselow, A. (2012). Subjectivity, intersubjectivity and the negotiation of common ground in spoken discourse: Final particles in English. Language and Communication, 32(3), 182-204.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2012.04.008]

-

Hey, J. H. G., & Agogino, A.M. (2007). Metaphors in Conceptual Design. Proceeding of the ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences & Computers and Information in Engineering Conferences.

[https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2007-34874]

- Ho, K. L. D., & Lee, Y. C. (2012). The quality of design participation: Intersubjectivity in design practice. International Journal of Design, 6(1), 71-83.

-

Kleinsmann, M., & Valkenburg, R. (2008). Barriers and enablers for creating shared understanding in co-design projects. Design Studies, 29(4), 369-386.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2008.03.003]

- Korea Tourism Organization. (2023). 노량진수산물도매시장. https://bf.ktovisitkorea.com.

- Laing, R. D., Phillipson, H., & Lee, A. R. 1966. Interpersonal Perception: A Theory and Method of Research. London: Tavistock Publications.

-

Mao, Y., Wang, D., Muller, M., Varshney, K. R., Baldini, I., Dugan, C., & Mojsilović, A. (2018). How Data ScientistsWork Together With Domain Experts in Scientific Collaborations: To Find The Right Answer Or To Ask The Right Question? Human-Computer Interaction, 3(237), 1-23.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/3361118]

-

Matthews, B., Khan, A. H., Snow, S., Schlosser, P., Salisbury, I., & Matthews, S. (2021). How to do things with notes: The embodied socio-material performativity of sticky notes. Design Studies, 76, 101035.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2021.101035]

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press.

-

Messeguer, R., Ochoa, S. F., Pino, J. A, Navarro, L., & Neyem. A. (2008). Communication and Coordination Patterns to Support Mobile Collaboration. 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design, Xi'an, China, 565-570.

[https://doi.org/10.1109/CSCWD.2008.4537040]

-

Oak, A. (2010). What can talk tell us about design?: Analysing conversation to understand practice. Design Studies, 32, 211-234.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2010.11.003]

-

Pifarre, M., & Staarman, J. K. (2011). Wiki-supported collaborative learning in primary education: How a dialogic space is created for thinking together. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6(2).

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-011-9116-x]

-

Schegloff, E. A. (1992). Repair after next turn: The last structurally provided defense of intersubjectivity in conversation. American journal of sociology, 97(5), 1295-1345.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/229903]

-

Schegloff, E. A. (1997). Third turn repair. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science Series, 4, 31-40.

[https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.128.05sch]

-

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). When 'others' initiate repair. Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 205-243.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.2.205]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. (2021). Dongmyo Flea Market. https://english.seoul.go.kr/dongmyo-flea-market-2/.

- Song, S., Dong, A., & Agogino, A. M. (2003). Time variation of design "story telling" in engineering design teams. In DS 31: Proceedings of ICED 03, the 14th International Conference on Engineering Design, Stockholm (pp. 423-424).

-

Valkenburg, R., & Dorst, K. (1998). The reflective practice of design teams. Design studies, 19(3), 249-271.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(98)00011-8]