Transforming the Batik Tiga Negeri (Three-Countries Batik) in Pleats to Represent Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand’s Batik Heritage by Applying the ATUMICS Method

Abstract

Background Batik Tiga Negeri is unique in the Indonesian batik repertoire due to its outstanding production process with intricate, dense, and beautiful motifs. This batik, which was first developed at the end of the 19th century, has a unique production concept across three workshops in Java, using red, blue, and soga/brown colors. Each production site manufactures three distinctive visual patterns on one piece. Batik has also been developed with varying characteristics in Malaysia and Thailand. Therefore, this study developed a contemporary concept to integrate three typical motifs from these three countries into one piece of batik, to strengthen the batik repertoire of each country and Southeast Asia.

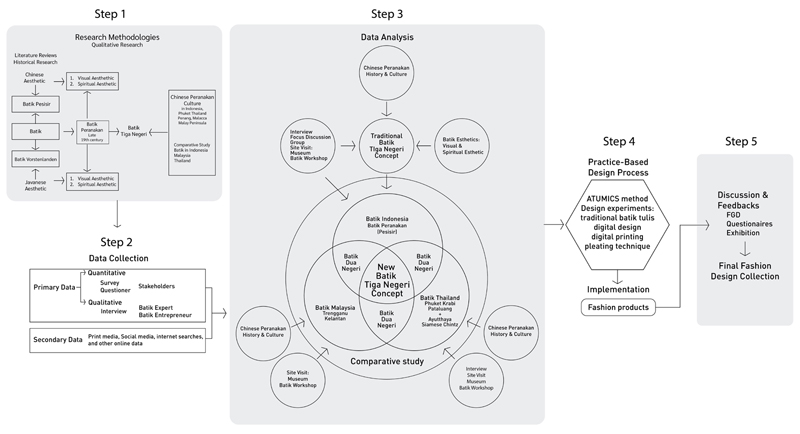

Methods This study was divided into five steps, with the first based on literature study, followed by direct observation through visiting batik workshops and textile museums in Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia. In the third step interviews were conducted with batik industry practitioners in three countries to gain insight into the uniqueness and understand market needs to help the creative process of developing contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri. The fourth step was conducting an experiment based on the analysis results, which were processed using the traditional transformation method, namely ATUMICS, followed by the design and production process using digital print technology and pleating techniques. Fifth, contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in pleats is applied as a fashion product with modern value.

Results The contemporary concept evolved from the traditional transformation of the original concept, resulting in the contemporary visual aesthetics of the three countries. This new artifact showed a modern and appealing evolution of batik that resonates with the younger generation. Therefore, the seven stages of contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats development were designed for utilization and enhancement by people in the batik creative industry.

Conclusions The harmonious and appropriate application of the ATUMICS method led to the production of new artifacts capable of maintaining cultural and modern values based on local wisdom. The concept is important in this method because it is the most resilient to facing extinction. This study produced three artifacts, contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri with an integration of visual styles from three countries into a single design, a style with pleated or accordion texture, and the fashion application.

Keywords:

ATUMICS, Batik Tiga Negeri, Contemporary, Pleats1. Introduction

Batik, which originated from the Indonesian-Malay language, is a traditional process of dyeing cloth using a resist method, requiring covering an area of fabric with dye resistant materials to prevent color absorption (Roojen, 2001). This ancient method requires the use of wax, vegetable paste, and mud on cloth to resist color. Batik can be found in China, Japan, India, Thailand, Europe, and Africa (Elliot, 2004), however, it was exquisitely refined to become the main art form in Java Island. Javanese batik attained the highest level of refinement through diverse repertoire of designs, well-developed dyeing methods, and technical perfection (Tirta, 1996).

This art form has become a masterpiece greatly admired due to the complex manufacturing process, unique colors, and complicated motifs imbued with rich symbolic meaning (Indarmaji, 1983). The visual and spiritual aesthetics are carefully represented in motifs and colors according to the intended creation process. Each motif holds reflective spiritual meaning associated with the wearer and conveys messages of hopes for the future. In Indonesia, batik motifs are closely related to philosophical or spiritual meaning, social status, religion, local culture, trade, and past colonialism (Jones, 2018; Sidhi et al., 2020). Pujiyanto (2010), stated that batik aesthetic is divided into two, namely visual and spiritual aesthetics. Visual aesthetic is the beauty radiated by the combination of lines, shapes, textures, and colors. While, spiritual aesthetics is the beauty associated with an understanding of faith in line with life philosophy. In this situation, the human relationship with God (Allah) is expressed through batik artworks.

The uniqueness of Indonesian batik lies in the spiritual aesthetic, which reflects the life philosophy embraced by the people. This spiritual aesthetic differentiates Indonesian batik from the counterparts in other countries. Based on the visual aesthetic, batik is perceived as an integral part of daily activities, embedded in traditional rituals such as childbirth, weddings, and funeral ceremonies. In addition, this art form also plays a critical role in various ceremonies or rituals performed within kraton (palace), such as in Solo and Yogyakarta.

The excellence of Javanese batik is further proven by the artisans who draw the motifs with absolute accuracy on both sides of the cloth. According to Veldhuisen, (2007), this method known as nerusi requires skill and a high artistic taste. The method holds significant value, considering that making batik with only one high-quality side is already difficult and time-consuming.

Several ASEAN countries, such as Indonesia, Southern Thailand, and Malaysia, possess similar batik culture. In Malaysia, the states of Kelantan and Terengganu have been recognized as the birthplaces of Malaysian batik since the early 20th century, serving as a local commodity and tourist attraction. Each region is characterized by unique motifs, for example the Kelantan batik known for the floral designs, was inspired by traditional wood carvings and Islamic principles that discourage visual depictions of living things (APPBI Official, 2022). However, observations made at the Chai Batik workshop in Phuket, showed batik motifs are dominated by marine fauna themes and traditional floral patterns in the Lai Thai style (Thai Design). Laksmi (2010), stated that each batik area has a unique visual inspired by natural and socio-cultural conditions, resulting in diverse styles. Therefore, batik motifs serve as a medium for conveying feelings or expressions embodied in a visual form influenced by the environment (Lukman et al., 2022).

In Malaysia, batik is currently facing certain problems such as the perception that it is an old art unable to adapt to modern times. According to Razali et al., (2021), a critical issue is the sustainability of this industry, because 95.2% of entrepreneurs are worried over the lack of interest showed by the younger generation. The issue poses a significant threat to the development of human resources in the industry. However, 38% of entrepreneurs believed the community failed to appreciate batik as a high-value inheritance. The integration of batik into contemporary Malaysian society is diminishing, and this issue presents significant obstacles to the development and preservation processes.

Based on an interview with Mr. Santoso Hartanto, owner of the Pusaka Beruang Batik Lasem workshop, in Indonesia, it was gathered that the younger generation in Lasem was increasingly disinterested in continuing the batik business. This was due to the notion that the art is outdated, time-consuming, and less profitable financially, compared to other professions. In addition, Ms. Miftakhutin, a Rifai’yah Batik artist in Batang, Central Java, stated that the decreasing number of young experts in fine hand-drawn batik was due to the perceived difficulty in mastering the craft, and the lengthy training period required. These factors pose a significant challenge to the development and sustainability of the industry in both countries. Therefore, an effort is needed to preserve traditional batik methods, while exploring new avenues for product development using technological advances.

UNESCO recognized Batik as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on October 2, 2009, reported that the significance was beyond patterned cloth. In Indonesia, batik motifs have deep philosophical values and meanings, which have become part of societal life cycle. Batik is often used in the ritual process associated with birth, marriage and death. Each batik-producing area has distinctive motifs with philosophical values instilled by the local wisdom. Guided by adopted philosophies, batik artists design these works based on various intentions, hopes, and good wishes (Rismantojo, 2021).

Before UNESCO officially recognized batik, there was a widespread concern in Indonesia when news circulated that Malaysia intended to claim batik (Sari et al., 2019), resulting in a heated debate among netizens in various cyberspaces and social media platforms. Meanwhile, this art form had also reached the golden peak on Java Island, and is found in various regions worldwide. Collaborative efforts among countries can improve the development and preservation of batik culture. However, a significant problem is the perception that batik is an outdated cultural artifact, hindering the adaptation to modern times. Therefore, there is need to find innovative ways to revive batik with new value and relevance.

According to the oral tradition, Batik Tiga Negeri was created by moving the production to three different locations and dyed using the following colors, merah getih pithik (chicken blood red), indigo blue, and soga (brown) (Malagia, 2018). This batik, which appeared in the late 19th century, is known for the exceptionally detailed designs, quality, and time-consuming production, resulting in relatively high selling price. However, a distinguishing attribute is the creative concept, where each production site affixes distinct characteristics, producing a single piece with three visual styles. This led to the question, what if the creative concept were applied to produce a contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri, showing three visual styles from countries with a batik culture in one piece? The contemporary batik has the potential to enrich the batik repertoire in Southeast Asia, specifically in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. To enhance the modernity value, it is essential to use technological assistance in the textile industry, enabling broader acceptance, specifically among the younger generation.

In order to improve community appreciation, knowledge, and preservation of batik, the concept of Batik Tiga Negeri needs to be developed to meet the demands of modern society. This can be realized through the application of the ATUMICS, a traditional transformation method that was recently developed. The basic principle of this method focuses on arranging, combining, integrating, or mixing the essential traditional elements with modern ones (Nugraha, 2012).

2. Objective

The study aims to explore the concept of Batik Tiga Negeri, as well as develop visual styles for batik motifs from three different countries. In addition, experiments were conducted to design and apply the motifs on cloth, as a sustainable effort to preserve batik culture based on the contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri concept. The results obtained would introduce contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri with modern values.

3. Methodology

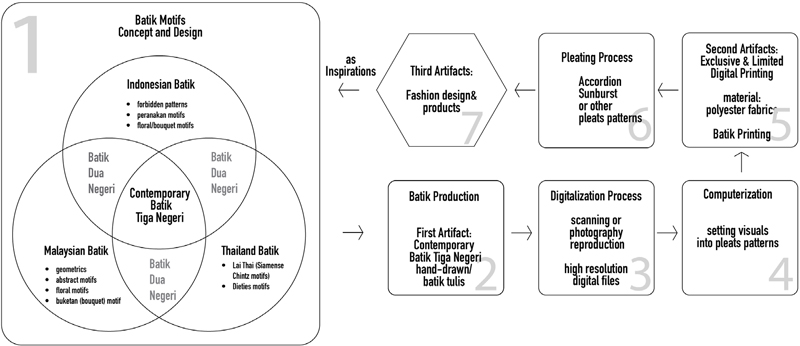

The practice-based study adopted both qualitative and qualitative methods including literature review, observations, interviews, and experiments. First, the history of batik development was explored, particularly focusing on the creative concept behind the production of Batik Tiga Negeri. Second, conducting studies on batik and other types of illustrated fabrics from three countries by visiting textile museums and workshops in Lasem, Central Java, Indonesia, Phuket, Thailand, and Kelantan Malaysia. The aim was to observe the batik process and examine the distinctive visual styles of each region. Third, interviews were conducted with practitioners of batik workshops, including Mr. Santoso Hartanto, Mr. Rudi, Ms. Miftakhutin, Mrs. Renny, Ms. Rosliza Muhammad, and Mr. Chai, the owners of Batik Pusaka Bear, Batik Kidang Mas, Kelompok Usaha Bersama Tunas Cahaya Batik Rifai’yah Batik, Batik Maranatha Ong, Leeza Batik, Kelantan Malaysia, and Chai Batik Phuket, respectively. The purpose was to address the current problems and gather insights about unique batik motifs. This included the exploration of market needs to help in the creative process of developing contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri. Fourth, the results of the analysis were processed using traditional transformation methods, namely ATUMICS, developed by Mr. Adi Nugraha. The creative process included designing and producing the new Batik Tiga Negeri as well as applying it using digital printing technology and pleating methods. Finally, the study was concluded with the production of contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri and the derivative fashion products instilled with modern values.

4. Batik Tiga Negeri

Batik Tiga Negeri is renowned for the unique concept and production process, setting it apart as being superior compared to other types. It is grouped under the Batik Peranakan category, developed by Chinese entrepreneurs residing along the northern coast of Java. Batik Tiga Negeri is believed to have been developed in the 1870s, and underwent a dyeing process with natural dyes in three different areas, namely red, blue and brown (soga) in Lasem, Kudus or Semarang, and Solo or Yogyakarta, respectively. With the discovery of synthetic dyes, the dyeing process could be carried out in one place, therefore the term Batik Tiga Negeri often refered to batik that has three colors red, blue, and brown including motifs resulting from the hybridization of coastal and court or inland styles (Lukman et al., 2022). Many experts believe that completing one piece of Batik Tiga Negeri requires traveling approximately 650 km, also known as the Batik Tiga Negeri triangle route (Malagina, 2018).

Map of Batik Tiga Negeri Triangle Route, Lasem-Pekalongan-Solo/Yogyakarta, Central Java. (Source: Author, 2021)

Roojen (2001) stated that the existence of Batik Tiga Negeri can be traced to the desire of the artists to produce a complex new type of premium batik by combining different motifs and visual styles. This trend is inseparable from the aesthetic tastes in a fashion style that occurred after the 1870s, which favored complicated designs. The prolonged processing time, often lasting for approximately eight months, contributed to the high cost of Batik Tiga Negeri. In addition, this premium hand-drawn batik was produced by the creative collaboration of artists from three different regions, reflecting cultural and ethnic diversity (Rizali, 2018).

Batik Tiga Negeri is the most expensive premium batiks in Java because of the high quality, and complicated motifs drawn on both sides of the cloth with exceptional precision. The expensive nature was also attributed to the large number of isen, known as filling motif, or complicated batik patterns and transportation costs incurred during production (Veldhuisen, 2007). This batik exemplifies the rich cultural ethnicity on the island of Java, with the color symbolism reflecting a blend of influences, red, blue and brown or soga representing Chinese, Dutch, and Javanese cultures. According to Laksmi (2010), each batik center or area has unique natural and socio-cultural conditions, contributing to the variations in visual styles. Therefore, batik motifs serve as a visual expression of feelings inseparable from environmental influences. The production methods, colors, and motifs of Batik Tiga Negeri are unique, reflecting a beautiful blend of cultures, in harmony with Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, the Indonesian motto of Unity in Diversity.

Mr. Santoso Hartono, owner of the Batik Pusaka Beruang workshop in Lasem, Central Java, stated that Batik Tiga Negeri has high aesthetic value and is complicated to produce. Therefore, many batik makers reluctantly engage in the production process because it is time-consuming, resulting in high selling price. There is a growing concern that this type of batik may become extinct, therefore, innovation is needed in the design, production process, and fashion application to maintain the richness of Indonesian visual culture. A new concept was developed in this study, including visual experiments and production methods aimed at producing Contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri.

5. Batik in Malaysia

The earliest form of Malay batik known as rainbow or Serian batik, was the basic form of resist dyeing (Perbadanan Kemajuan Kraftangan Malaysia/Malaysian Handicraft Development Corporation, 1981). This method was believed to have been introduced by Minah Pelangi from Terengganu during the reign of Sultan Abidin II (1794 to 1808), a renowned supporter of arts. Furthermore, in Kelantan and Terengganu, early Malay batik was developed by printing motifs using carved wooden blocks known as Sarang. The process was referred to as kain pukul (stamped cloth), and kain terap (printed or engraved cloth) in the regions, respectively. In 1920, two entrepreneurs, Haji Che Su bin Haji Ishak, and Haji Ali from Kota Bharu, Kelantan and Terengganu, simultaneously used wooden stamps (Sarang bunga, or flower nest) to make batik. Repeated designs were stamped on cotton cloth using a bluish-black pigment obtained from the bark of wood, instead of wax, therefore, this form of batik is not considered authentic.

In 1926, two of Haji Che Su sons, Mohd Salleh and Mohd Yusoff, used a type of screen printing (silk printing) method to produce inexpensive sarongs, an imitation of Javanese batik. The sarongs featured large flower bouquets similar to the Pekalongan style in the north coast of Java. The Kelantan and Terengganu regions witnessed significant breakthrough in batik development in the 1930s, closely related to the local production of sarongs, the earliest and most enduring costume in the Malay World. The decoration on sarongs was applied with wax from metal blocks (stamps), initially imitating imported ones from batik centers on the north coast of Java. Later, it was developed with unique Malaysian motifs inspired by nature, and Islamic laws, using geometric shapes to avoid representing living things.

Left, Batik Stamp Sarong. Source: National Textile Museum Malaysia, 2021. Right, Batik Paint by Leeza (Source: Author, 2023)

The carved batik motifs on wooden blocks found in museums or private collections revealed a striking resemblance to the f loral, faunal, geometric, and border designs prevalent on Javanese sarongs. The motifs included blossoming flowers, large floral bouquets, layered arabesques, vines, and triangular bamboo shoots known as pucuk rebung. The white background of the cotton or pattern is occasionally dyed, or hand painted. In the 1960s, the advent of metal block-stamp meters enabled entrepreneurs to expand batik production beyond traditional sarongs to include other clothing items. Since the 1970s, the adoption of the increasingly popular stylus or canting, had transformed batik making in Malaysia from a craft to an art (Yunus, 2011).

Ms. Rosliza Muhammad, an entrepreneur in Kota Bahru Kelantan who had 30 years in designing, stated that in Malaysia, batik is perceived as a trading commodity, unlike in Indonesia, where it is part of daily activities. According to Ms. Rosliza Muhammad, Indonesian batik has a strong influence on Malaysian batik, strengthened by Islamic laws. The resulting Malaysian batik avoids depiction of living things, presently, the popular motifs are f loral, and geometric shapes, including occasional representations of insects such as butterflies. The increasingly widespread use of a stylus or canting, made Batik Lukis (batik painting), the most popular type in Malaysia. Ms. Rosliza stated that Malaysian batik is more contemporary compared to traditional Javanese (R. Muhammad, personal communication, August 6, 2023). The problem faced in the Malaysian batik development is the limitation of motifs, and the assumption among young Malaysians that it is outdated. Therefore, Malaysian batik lacks a strong identity compared to the Indonesian counterpart (Kari et al., 2018).

6. Batik and Siamese Chintz in Thailand

The Thai refer to batik as Pate, Pha Phan or Pha Batik Phan, meaning wrapping around the body. Local people in southern Thailand call batik Pha Pa Tae or Pha Ba Tae, influenced by Indonesian culture, introduced through Malaysia due to commercial and religious activities. Batik is often believed to have originated from the Royal Court of Indonesia, with Javanese batik later spreading throughout Europe by the Dutch. Batik fabric was first introduced by Mr. Wae-Ma Wae-Aarree, a Malay-Thai, in Su-Ngai-Kolok District, Narathiwat Province (SACIT, n.d.-a).

In Thailand, diverse societies have an influence on sources of batik motifs and production methods. However, these motifs depict several symbolic meanings related to Thai and local wisdom. Archaeological evidence, attributed the influences to two sources 1, for example in the north, it was influenced by the Chinese through the Hmong community and is referred to as hemp indigo batik. This batik, produced in Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, Nan, Phrae, and Petchabun Provincial home industries, featured mainly geometric designs. 2. In the south, it was influenced by Java or Indonesia through the Malaysian community residing along the borders of the four southern provinces, namely Narathiwas, Pattani, Yala, and Satun. The batik motifs show both the local identity of the people and nature, while the patterns were inspired by the imagination of the craftsman, environment, identity as well as local culture. (SACIT, n.d.-b). However, unlike in other countries, Thailand, views batik as a handicraft or Batik Painting, drawn by hand. Thai batik has characteristics that distinguishes it from similar art found in other countries.

Left, Floral Batik Painting and right, Marine Batik Painting by Chai Batik Phuket. (Source: Author, 2021)

Ajarn Chai, stated that the theme often shown in Phuket batik motifs is the ocean flora and fauna because of the influence of the environment. In addition, vibrant colors are used, alongside motifs that express the local identity, reflecting the image of the ocean. Prior to developing and establishing the Chai Batik workshop in Phuket, Ajarn Chai studied batik in Malaysia. On average, the batik produced is stamped, painted, or a combination of both, with the aid of a custom-developed canting tool. This popular product generates income for people in the Andaman Region and other communities across Thailand despite being less popular among the younger generation. Batik is more of a tourist commodity, asides from being popular in several government agencies in Phuket as official uniforms (Chai, personal interview, November 20, 2021).

7. Pha Lai Yang or Siamese Chintz

Thailand also has a distinctive type of illustrated or painted cloth known as Siamese Chintz. It is a super fine quality imported textile using high-quality cotton from India. According to Crill (2008), chintz textiles are Indian cotton fabrics with hand-drawn patterns made using mordant-dyed bamboo pens (Kalam) and resist. In Thailand, the textile is also known as Pha Lai Yang, meaning fabric made according to model-based design. During the Kingdom of Ayutthaya (1569 to 1767), the Siamese court restricted the use of this elaborate and rich textile to members of the royal family. Highly skilled Siamese artisans designed motifs and patterns, shipped to the Coromandel coast of India for chintz production (Smanchat, 2021).

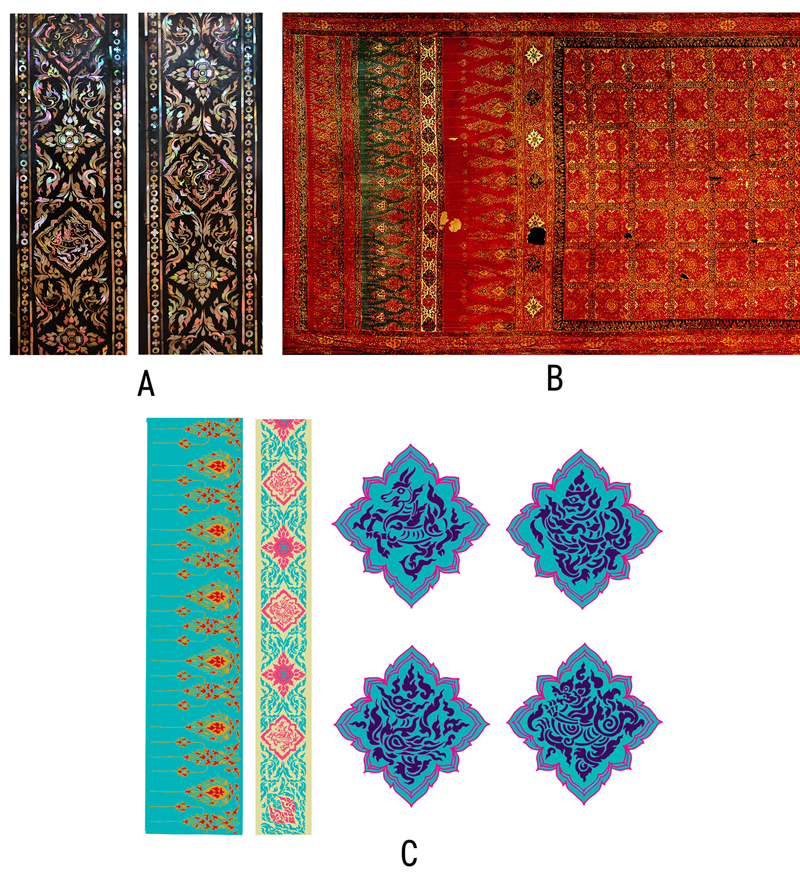

The Siamese royalty and court gave special attention to the quality of the textiles and patterns imported. As a result, the Siamese chintz has a unique and distinct visual design compared to other Indian chintz produced for British, the Netherlands, Malaysia, and Indonesian consumers. Thai motif designs, themes, and aesthetic perspectives are the main characteristics that must be imprinted on royal textiles, ensuring distinction from foreign ones (Smanchat, 2021). The elaborate and elegant motif designs have certain features known as Lai Thai (Thai designs), characterized by the seamless flow of lines and delicate pattern. Lai Thai motif express the following qualities delicacy, sweetness, tenderness, and love for beauty (Monteil, 2017).

The composition of the Siamese Chintz has a symbolic meaning and highly valuable in the Siamese court. This fabric generally consists of a center field piece, a border roll, and four sets of ribbons in the end panel. The arrangement of motifs on the ribbon denotes the prestige of the cloth and the wearer, with gold adornment elevating the value, reserved exclusively for the King. Based on the distinctive visual style in Thailand, contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri motifs are inspired by the elegant patterns of Siamese Chintz Lai Thai.

8. Batik in Chinese Peranakan Communities

Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia have Chinese Peranakan communities with strong cultural ties, a typical example is the use of batik among the women. Chinese Peranakans or Baba and Nyonya are people of mixed births during the 15th to 19th centuries because of a century-long history of transculturation and interracial marriage between Chinese immigrants and the local people in Southeast Asian countries, such as Indonesia, the Malay Peninsula (Penang, Melaka, Singapore), and Phuket province in Thailand. This culture is distinguished by the unique hybridization between the Chinese and the local people in Southeast Asian countries, shaped by European influences during colonialism (Rismantojo, 2021). In addition, the young Chinese Peranakan women usually wear batik sarong, a tubular cloth worn around the waist, also popular with ladies in Southeast Asian countries (Muneenam et al., (2017).

Most Peranakans are from well-educated and wealthy families and prefer expensive, premium hand-drawn batik. The Chinese Peranakan women wore batik sarongs for the daily activities, particularly the colorful Batik Peranakan, adorned with bouquets or floral motifs. This hand-drawn batik is also a popular choice of wedding dowry and family heirlooms passed on to future generations. Therefore, batik was effortlessly integrated into Peranakan life in three different areas, with floral and bouquet motifs used as an icon representing the culture.

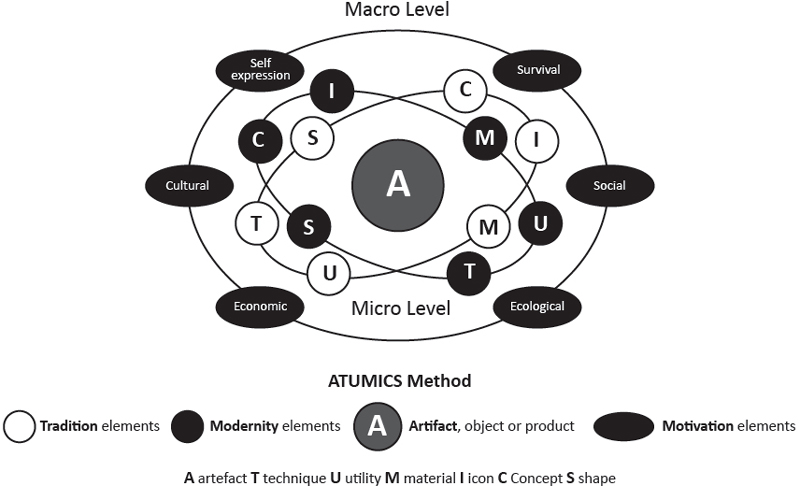

9. ATUMICS Method

The study focused on transforming tradition to adapt to the survival and sustainability in modern society. Adhi Nugraha developed the ATUMICS method, aimed at transforming or revitalizing traditional designs. According to Nugraha (2019), the philosophy behind this method focused on the continuous efforts needed to ensure the survival of this tradition in accordance with modernity. Therefore, tradition must be connected with all aspects of life, in order to be accepted by modern society. Traditions that are static and no longer developing according to the developments and needs of the times tend to gradually become extinct. The main objective of the ATUMICS method is to provide artisans, craftsmen, designers, students, and practitioners with an applicable method related to tradition revitalization.

Nugraha (2019), stated that there are six fundamental elements of the ATUMICS concept, at the micro level. The letter A represents an artifact, product, or object which is the center of traditional revitalization activities. The six essential elements in producing new objects are Technique (T), comprising all kinds of knowledge or methods for making objects, such as production techniques, processes, skills, equipment, and other facilities. Utility (U), focused on the functionality and usability of a product, ensuring it meets the needs of the users. Material (M) is all kinds of raw materials used in making objects and traditional products. Icon (I) representing all images found in nature, ornamentation, colors, myths, people, and artifacts. Concept (C), hidden elements or profound messages embedded within physical forms and objects. In addition, this element is believed to be the most resilient from the threat of extinction. The concept as a hidden element can broadly be in the form of customs, norms, habits, beliefs, ideology, and culture. The role of these hidden elements is vital in the process of revitalizing tradition. Shape (S) refers to the performance, appearance, or physical attributes of an object, such as dimensions, gestalt, and shape.

Figure 7 shows six components of the motivational background to revitalize traditions or produce new objects at a macro level. The components comprise (1) Cultural, the need to preserve old culture eroded by modernization, (2) Social, the need to enhance societal values through traditional practices, (3) Ecological, the need to restore environmentally-friendly traditional elements. (4) Economic, the need to enhance economic value through traditional means, (5) Survival, the need for traditions not to become extinct and (6) Self-expression, the need for artistic expression and creativity (Sutrisno, 2020). These components are closely related to the six fundamental elements discussed earlier. In the early stages of creating a new object, there is need to formulate a harmonious balance between all the components. Furthermore, the production of any art work can have different emphases and motivations. This includes structuring, combining, integrating, or blending elements of tradition with modernity (Suriastuti et al., 2014).

10. Transformation Process

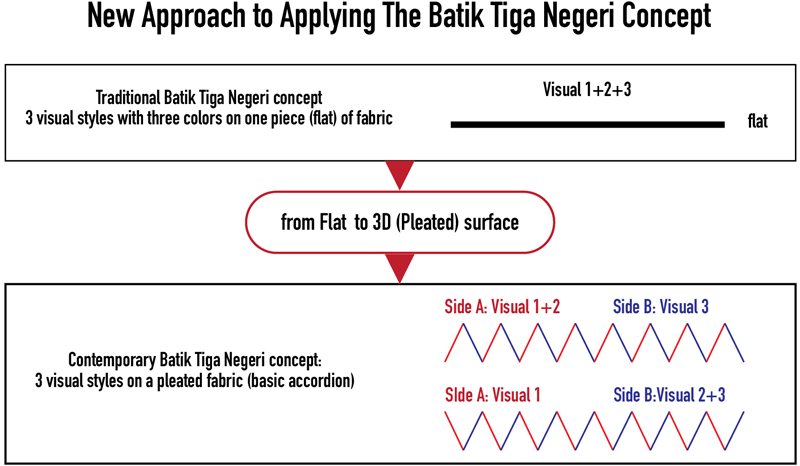

The unique creative concept of Batik Tiga Negeri enables the development into contemporary batik. Furthermore, using textile technology, enables the development of batik with new visual appearance and dimensions. The transformation helps revitalize Batik Tiga Negeri and provides a new alternative suitable for fashion applications.

The transformation process starts with determining the motivations underlying the notion that Batik Tiga Negeri needs to be preserved and developed. The motivations include survival, culture, social, and economy, at the macro level. In addition, these motives underlie the selection of traditional elements that need to be maintained and the ones to be readjusted.

Survival

The survival motif relates to the need for Batik Tiga Negeri to be continuously developed. The difficulty and time-consuming nature of hand-drawn batik production process, often lasting several months, results in high selling price, considered unprofitable for entrepreneurs. Furthermore, skilled workers are also decreasing due to the declining interest of the younger generation in continuing the tradition. Entrepreneurs in Thailand and Malaysia also experienced this phenomenon, prompting a preference for the production of batik cap (stamped) and lukis (painted batik), compared to hand-drawn ones with canting

Cultural

Batik, known for reaching artistic pinnacle in Java, had also developed in Malaysia and Thailand, with each region showcasing visual styles shaped by environmental, social, and cultural influences. In addition, the integration of local wisdom adds value through storytelling, meanings, and philosophies that enriches each batik. Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand possess unique batik cultures distinguished by distinct characteristics.

Social

Batik culture in these three countries serve as a tool for socialization and cooperation. However, from a social perspective, batik is an aspect of tradition, because it is worn daily or at certain events and rituals.

Economic

The results of the transformation process are expected to add to the economic value of Batik Tiga Negeri through digital printing technology and pleating. The aim is to provide entrepreneurs with alternative types of contemporary batik, thereby increasing income and enriching the batik repertoire.

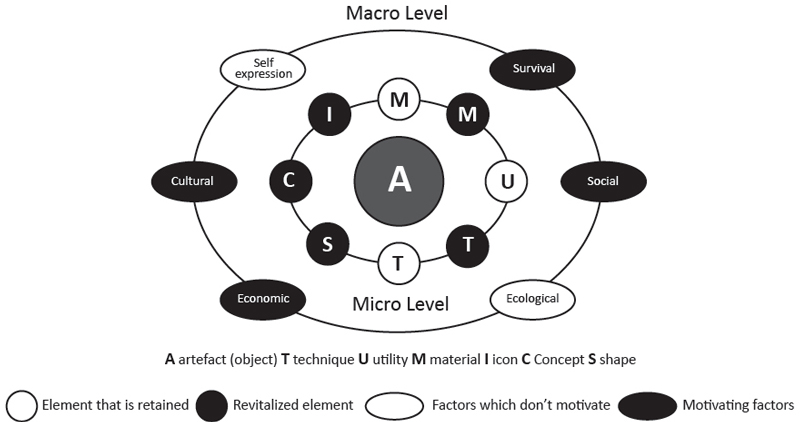

Based on the identified motivations, it was detected that certain elements needed to be transformed, and maintained. The elements that need to be transformed are Technique, Material, Icon, Concept, and Shape, while the ones maintained included Technique, Material, and Utility.

11. Pleats and pleating

Methods and shapes of pleating

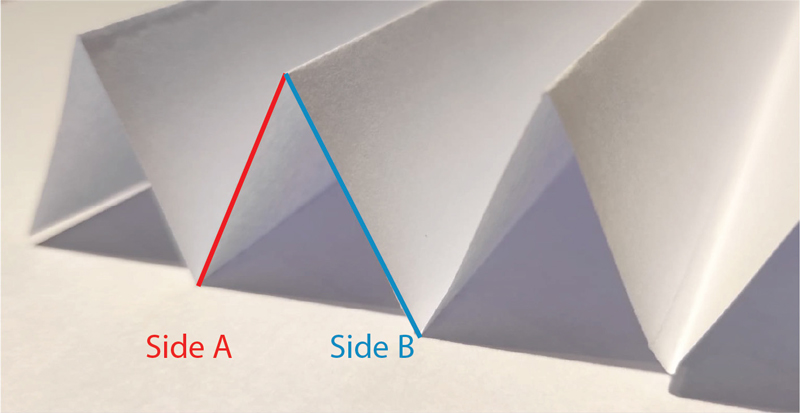

Pleating is a type of textile manipulation that had progressed alongside advances in materials and technology. According to Kalajian et al. (2017), it is the systematic creasing of fabric or other materials resulting in precise symmetric, non-symmetric, or organic-looking folds. Additionally, Huang (2021) stated that manual processing was the first type of pleating method practiced. This method entailed pressing the pleats manually, using an iron. The second type was the continuous machine method, which requires the use of an automatic machine to produce pleats. It is currently the most commonly used method in the industry. The third type was the hand pleating method, which entailed the use of two molded sheets of kraft paper to sandwich the textile by applying a heat-steaming process. The three types of pleating methods were subjected to thermal process, and the classification criteria depended on whether the pleats were formed by hand, machine, or kraft paper.

The aesthetic advantage of pleating is the ability to visually enhance the geometric shape of the garment, while creating a unique texture. Moreover, the three basic classical shape are accordion, side, and box pleats. This research focused on accordion pleats, a series of pleats made on fabric or other materials in alternating directions while maintaining similar symmetrical distances between each peak and valley (Kalajian et al., 2017).

In this research, the experiments applied the continuous machine and hand pleating methods to produce accordion pleats, as shown in Table 1.

Based on these results, the hand pleating method was used in this research. The method manually arranges the digital-printed textile, placing it precisely alongside the kraft paper molds.

Analysis of diverse designs using several pleating methods

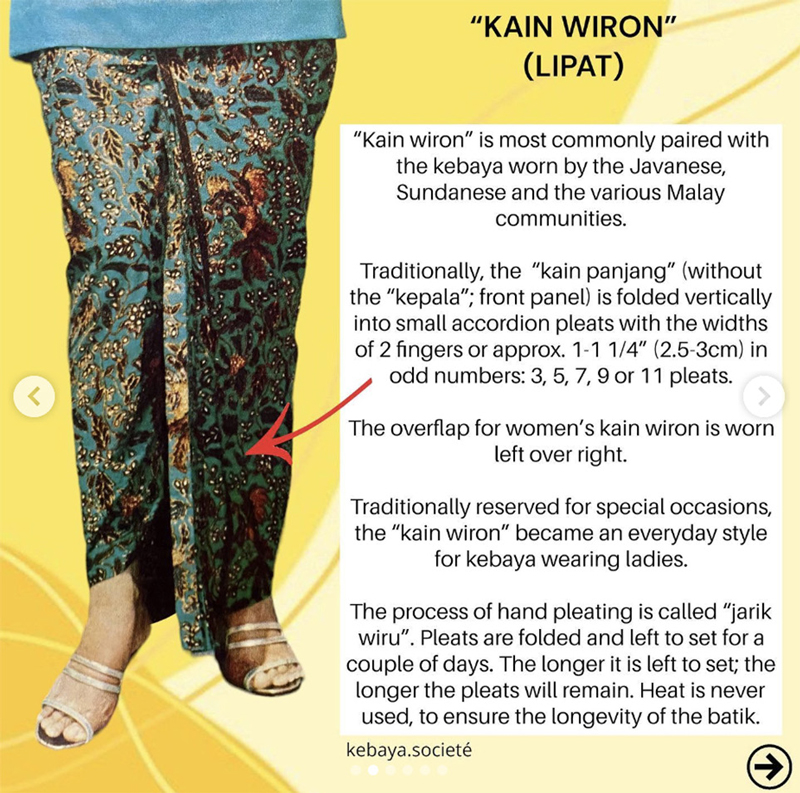

Kain Wiron (wiron cloth)

The concept of pleating for this study was inspired by Kain Wiron (wiron cloth), particularly the traditional practice of pleating batik cloth through a manual folding process by hand called jarik wiru, popular among Indonesians, specifically in Java. Traditionally, long batik cloth is folded vertically into small accordion pleats two fingers wide (2.5 to 3 cm), with an odd number of folds, commonly 3, 5, 7, 9, or 11. Kain wiron was initially used for special occasions, before it eventually became a daily attire for women. After folding, the pleats were left to dry for several days, enabling it to harden naturally for increased durability. According to Kebaya Societé, (2023), heat is never used to ensure the longevity of the batik. Kain Wiron was included in the manual processing category despite not applying any form of heat.

Pleats Please by Issey Miyake

Issey Miyake is a pioneering fashion designer renowned for innovative and avant-garde design methods. Miyake design philosophy surpassed traditional boundaries by effortlessly integrating art, technology and functionality. This renowned designer focused on the piece of fabric concept, exploring the transformation of two-dimensional materials into three-dimensional forms that interact harmoniously with the human body. The philosophy led to the origin of signature pleats and the Pleats Please line, which revolutionized garment construction and aesthetics (Li, 2023).

The iconic achievement of this brand was the introduction of the Pleats Please product line in the early 1990s. This collection showcased the mastery of pleating methods allowing for an infinite variety of shapes. The heat treatment method adopted was used to produce visually appealing, durable, and travel-friendly pleats. The quality of the polyester used for the formation process was also essential to the success of the product line.

Issey Miyake creative team further implemented and developed the continuous machine method, because it allows pleats production in large quantities, while having a consistent appearance according to the desired design. Figure 11a shows models in a sequence of flawless, flexible dancing movements, depicting the comfort of the Pleats Please product. While Figure 11b is the outcome of a collaboration with artist Yasumasa Morimura, who used Pleats Please as canvas to create art on clothing. The collaborative project expanded the potential of clothing as a communication tool, further strengthening the ties between art, fashion, and technology (Miyake, 2012). These works inspired the idea of Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats with digital print technology, revealing two different visuals on both sides of the material, thereby producing a unique visual effect while in motion.

12. Discussion

Practice-based study refers to an investigation of new knowledge that uses both practical application and subsequent results. When a creative artifact serves as the foundation for knowledge contribution, the study is categorized as practice-based (Joneurairatana, 2021). Therefore, this study is categorized as practice-based because the outcomes are artifacts that make new contribution to the development and application of batik design in fashion.

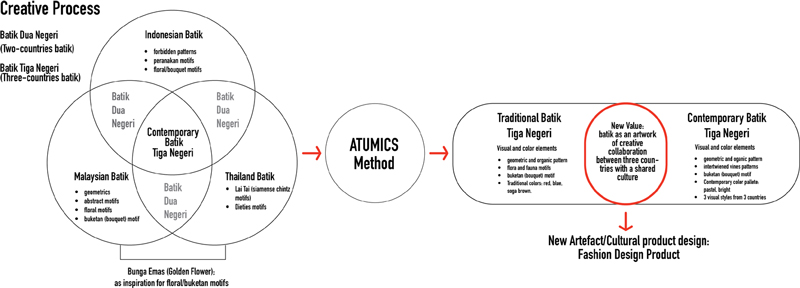

The ATUMICS method was used to transform the traditional concept of Batik Tiga Negeri. Initially, three visual styles were applied on a piece of batik from each workshop in three cities in Central Java, Indonesia. However, the new concept was expanded by focusing on designing contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri, incorporating visual styles from three countries with batik culture. Unlike the traditional one, the contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri concept, had several colors.

The implementation of the new Batik Tiga Negeri concept includes modifying the appearance of the icons, representing each country. The icons selected to represent Indonesia are the Parang-Rusak and the Kawung motif, simplified to have a modern appearance. Initially, these motifs were categorized as forbidden, reserved only for the royal family and high court officials as part of state dress in the sultanates of Solo and Yogyakarta, according to royal decrees (Gluckman et al., 2018). Presently, the motifs can be used freely outside the court but must be applied wisely to respect the sultanates.

The Parang-Rusak motif is among the oldest motifs in Indonesia and the most favored batik pattern in Central Java. The term often interpreted as broken knife – originated from the Indonesian word parang meaning machete or knife. The traditional Parang-Rusak motif signified that humans should be able to control temptations and desires to cultivate noble character and behavior (Parmono, 1995). Koeswadji and Parmono (2013), stated that the Kawung and Parang-Rusak motifs were designed by Sultan Agung Hanyokrokusumo, ruler of the Mataram kingdom, in the seventeenth century. The creativity portrayed by Sultan Agung was inspired by nature and simple objects, designed into beautiful batik motifs.

The Kawung motif was inspired by the sugar palm tree, particularly the distinctive white oval-shaped fruit called kolang kaling (sugar palm fruit). Based on the description of palm fruit or kolang kaling , the motif is symbolic, the trunks, leaves, fibers, sap, and fruits, are beneficial to humans. Traditional Kawung motifs convey messages and aspirations that motivated people to embrace excellence, kindness, and societal value, fostering a sense of contribution to the nation (Parmono, 2013).

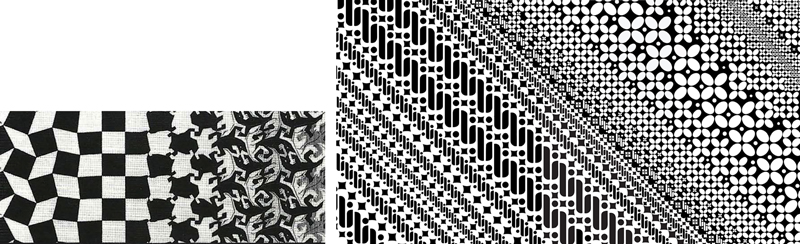

The newly modified Parang-Rusak motif is designed to morph into the Kawung and vice versa. This morphing process was inspired by the work of M. C. Escher, who is famous for combining meticulous realism with enigmatic optical illusions and unexpected metamorphoses of objects (Britannica, n.d.). The process reflects the idea that humans have the capacity to control temptations and desires, to cultivate noble character and virtuous behavior. Furthermore, by embracing excellence, kindness and societal value humans contribute meaningfully to the betterment of the nation.

Left, Metamorphosis, 1967 - 1968, by M.C. Escher. Right: Parang-rusak Kawung Batik motif. (Source: Author, 2022)

In Indonesia, batik motifs signify an event or a period, a typical example is the Batik Pagi-sore meaning morning-evening. This style features two kinds of batik motifs and patterns with a contrasting background dark and light on a piece of cloth divided diagonally. With the intention that one batik cloth can be used twice, in the morning and evening with two different patterns. Batik Pagi-sore , developed during the Japanese colonial period in Indonesia, reflects the difficulty of obtaining textile materials and the hardship endured during the Japanese occupation. Although the motifs and patterns are smooth and beautiful, the design convey a satirical meaning about a period full of suffering (Asa, 2006). This type of batik with pagi-sore format became synonymous with the Japanese occupation period from 1942 to 1945.

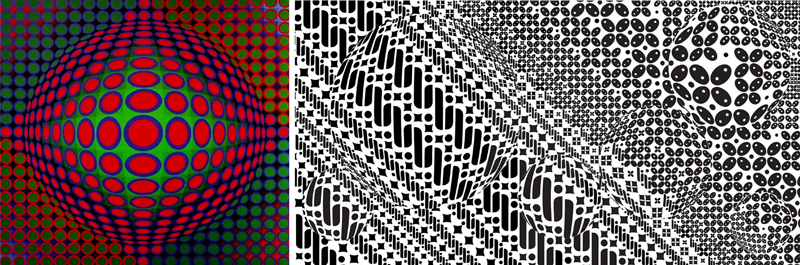

The contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 to 2023), proven by uniquely designed features. The uniqueness focuses on the disturbance of the Parang-rusak kawung motif in the form of an optical illusion. Inspired by the work of Victor Vasarely, the French-Hungarian artist (1906 to 1997), known as the originator of the Op-Art movement, the design was precisely based on geometric shapes and colors, to evoke hallucinations of optical vibrations (Hall-Duncan, 2022). The resulting optical illusion visual effect depicts the disruption experienced by people during the pandemic, thereby establishing it as the hallmark of contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri.

Left, Artwork by Victor Vasarely. Source: Hall-Duncan, 2022. Right, Parang-rusak Kawung batik motif with optical illusion. (Source: Author, 2022)

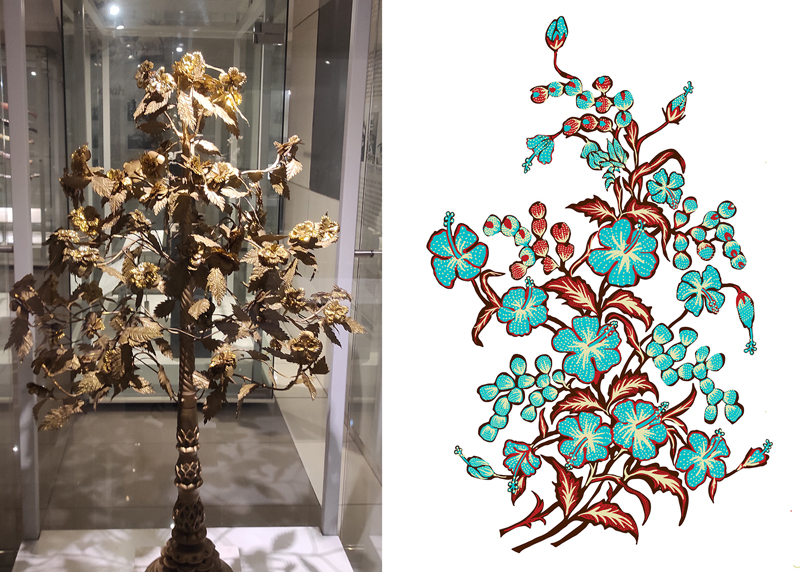

The icon selected to represent the Malaysian batik design is a bouquet, reflecting the common use of floral motifs. Initially, there were fauna motifs, which was rarely shown and abandoned over time. Therefore, the icon representing Malaysia is a floral motif arranged into a bouquet of kembang sepatu flower (hibiscus), the official flower of the nation.

The selection of the bouquet motif as a Malaysian icon was based on two reasons. First, the three countries have Chinese Peranakan culture, where women wore Batik Peranakan, dominated by f loral or bouquet motifs in bright or pastel colors. Second, based on the historical ties between Malaysia and Thailand, from the 14th to the 19th century, the Malay kings of the northern Peninsular Malaysia (Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu, and Patani) delivered Bunga Mas (Golden Flower) made of quality gold to the King of Siam in Bangkok, every three years as a symbol of friendship (Muzium Negara, 2023). In reciprocation, the King of Siam sent gifts of similar value (Bin Ghazali, 1978). Saidon and Suib (2017), stated that the delivery signified loyalty and friendship between the Bangkok kingdom and Malay countries such as Kedah, Kelantan, and Terengganu. Therefore, the bouquet arrangement was selected as the suitable icon to represent the Malaysian visual style.

Left, Bunga Mas, The National Museum of Malaysia. Source: Author, 2022. Right, Kembang sepatu flower Bouquet. (Source: Author, 2022)

The icon representing Thailand was derived from Lai Thai (traditional Thai art), the hallmark of visual art in the country. Lai Thai served as the basis for various Thai artwork such as ornaments, temple paintings, and visuals on Siamise Chintz. The visual elements developed into the Thai Icon originated from the details of the Siamise Chintz during the Ayutthaya kingdom era. It was further complemented by a visualization of the mystical creatures in the Himmapan forest, responsible for protecting the followers of Buddha. The mystical creatures were inspired by the 263-year-old Mother-of-Pearl Inlays of the Door panel of the Emerald Buddha, placed in the National Museum Bangkok.

A. Ornament of Himmaphan forest mystical animals on mother in lay door courtesy of National Museum Bangkok. B. Siamese Chintz (Source: Smanchat, 2021). C. Visual design adaptation for contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri (Source: Author, 2022).

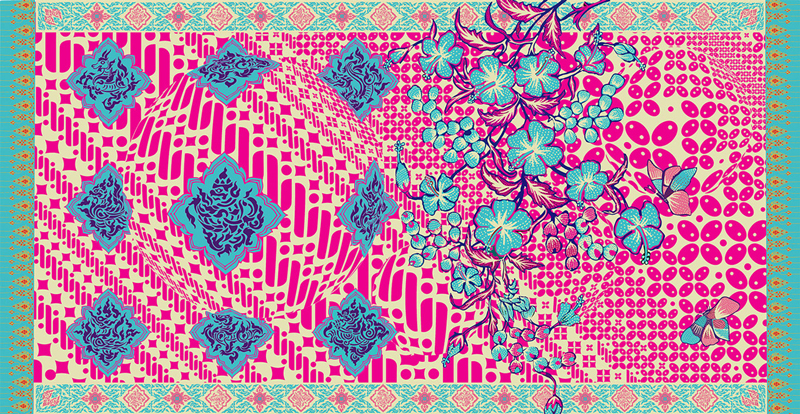

Figure 17 was the first contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri design, with a concept featuring three distinctive visual styles from three countries. The pastel colors applied in this design, were based on the Batik Peranakan palette, while the initial experiment conducted in three different workshop locations in Lasem used the traditional colors merah getih pithik , indigo blue, and soga brown. This batik design is an expression of prayer to the Almighty for protection as well as signified collaborative effort in facing the hardships brought about by COVID-19. The impact of the pandemic caused an illusory disturbance in the parang-rusak kawung motif. Bouquets and butterflies represent optimism, hope, and unity, reflecting a positive gesture towards overcoming difficult times and thriving together. In addition, the spiritual aesthetics of this batik lies in the message conveyed.

In the second batik design, an iconic floral bouquet was designed using the national flowers of the three countries, depicting cultural diversity bound by regional and historical relations. The visual design was inspired by the Indo-Dutch batik style which gained popularity in the late 19th century, known for the prominent use of bouquet motif. In addition, batik with f lower bouquets is popular, specifically among the Chinese Peranakan community in Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia (Lukman et al., 2022). The national flowers of each country were selected, namely anggrek bulan (Phalaenopsis amabilis), kembang sepatu (Hibiscus), and the Ratchaphruek (Cassia Fistula Iinn) representing Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, respectively.

The bouquet design was perfected with the inclusion of chrysanthemums and butterfly motifs representing the Peranakan culture. The butterfly, and Chrysanthemum, signified long life and the sun with the radiant blossoms, or the center of the cosmos (Achjadi & Damais, 2006). These motifs were applied to pay homage to the Chinese Peranakan entrepreneur who developed Batik Tiga Negeri. However, blue was selected as the background color to represent the influence of Indo-Dutch Batik. The batik design reflects the relationship between the three countries, which is always blossoming, long-lasting, and mutually beneficial.

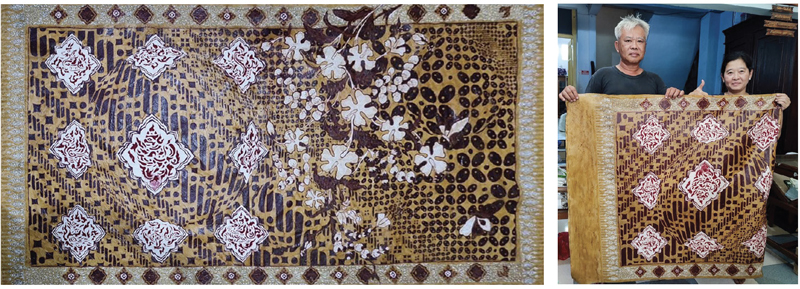

The production process comprised two stages namely techniques and materials. In the first stage, traditional techniques were used, including drawing with wax and canting, followed by the three-color dyeing process. This resulted in Batik Tiga Negeri with contemporary motifs in traditional colors, using prisimina cotton, a popular fabric material. In the second stage, the newly produced Batik Tiga Negeri was subjected to a digitization process, through digital photography reproduction. The images are processed digitally using the Adobe Photoshop program to achieve various color variations. The modified results were digitally printed onto the fabric. To be permanently pleated, the materials were changed from cotton to polyester fabrics such as satin, organdy, and chiffon. In addition, Figure 16, shows the process of designing contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri, referring to the traditional concept adopted in three different workshops in Lasem, Central Java.

In the initial production stage, patterns and motifs were carefully drawn or traced on the cloth using a pencil. Furthermore, the wax was carefully applied to the cloth using a canting tool, covering the parts selected not to be colored. The cloth was dyed red, based on the tradition of creating Batik Tiga Negeri, to produce a perfect merah getih pithik . After the drying process, the cloth was boiled to remove the wax. This first stage was carried out by batik artisans at Kidang Mas Batik workshop, operated by Mr. Rudi Siswanto and his wife, Mrs. Vina.

Figure 20 shows the second stage of the process, where distinctive isen motifs were drawn on the bouquet at Mr. Santoso Hartono Pusaka Beruang workshop. In addition, wax was applied to cover the parts intended to remain uncolored, before proceeding to the blue dyeing process.

In the third or final stage, the production location was moved to the Pesona Canting batik workshop owned by Ms. Sugiyem. The distinctive endog walang or grasshopper eggs motif, was incorporated before the final dyeing process using soga brown color.

The next step was the process of digitizing the batik cloth, and the picture in Figure 23 shows the result of digitization realized by transforming colors using Adobe Photoshop software. The process includes changing the shape of batik cloth from the typical two-dimensional form into three-dimension with the help of pleating technique.

In this pleating process, side A displays the Batik Tiga Negri Flower Bouquet, and side B displays the contemporary Batik Tiga Negri design, respectively, digitally printed on the fabric. The following process is pattern pleating, where the fabric is folded and sandwiched between the sides of the mold, and then steamed in an industrial steamer. The mold, made from card stock folded into a specific shape, aids in the process (Kalajian et al, 2017). After a precise pleating process in line with the design, the fabric had an accordion texture with a visual illusion, showing two batiks in one piece, particularly evident when in motion. The final result is a contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats artifact, as shown in Figure 25.

Left, Pleated Batik Tiga Negeri. Right, Contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats dress. (Source: Author, 2023)

The next step includes integrating contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri to ready-to-wear clothing designs. The blossoming flower concept, inspired by the meaning conveyed by the design, depicting optimism and post-pandemic sense of renewal. The satin fabric gives it a shiny, luxurious, and sophisticated appearance, designed with simple, cheerful and f lowing silhouettes. In line with the theme, the basic design of this collection resembles a blooming f lower with bright and cheerful colors, such as spring. This ready-to-wear design aims to prove that contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats offers a modern alternative that resonates with the fashion trends and appeals to the young generation.

The Contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats is a new artifact included in the batik imitation category, realized through digital printing from the original batik. Developing this concept, maintains the sustainability of batik in ASEAN region and provides entrepreneurs with opportunities to expand artistic business ventures.

13. Proposed Design Process for Contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats

The proposed design process for developing a contemporary Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats, is divided into seven stages. The first stage includes acknowledging batik, as a narrative medium that requires the creation of motifs with cultural significance, relevant to each country. When producing Batik Tiga Negeri, it is essential to prioritize countries with strong batik culture to enhance relevance. In this stage, the motifs and patterns are designed based on detailed investigation of the visual cultures of each country.

In the second stage, after the motifs and patterns have been transferred to the fabric, a hand-drawn batik version was produced. This version served as the primary artwork intended for preservation as artifact documentation, and subsequently, added to the batik design repository of the corresponding workshop.

The third stage includes transforming the completed hand-drawn Batik Tiga Negeri into a digital format. This process is accomplished by taking high-resolution professional photographs or using an industrial scanner. The quality of the images are essential for achieving better digital printing results.

The fourth stage required combining two batik patterns into a single pattern, customized to meet the design needs, such as sunburst, accordion, or other pleating types. Once the design of the pattern incorporating both batik visuals has been produced, the fifth stage entails digitally printing it on the fabric. To maintain exclusivity, the digitally printed batik must be limited, documented, and numbered, similar to the reproduced artworks. The use of polyester-based fabric was recommended for the pleating process to produce permanent pleats. The fabric is pleated in the sixth stage after the digital printing process had been completed. This can be performed using a pleating machine or manually by hand.

In the seventh and final stage, the pleated Batik Tiga Negeri, was ready to be designed into various silhouettes according to the artistic vision of the designer. The contemporary pleated design is categorized as either batik printing or imitation (batik imitasi).

The design process was organized based on the outcomes of the focus group discussion with batik entrepreneurs in Lasem. According to the entrepreneurs, the production process starts with hand-drawn batik, while the results of digital printing is referred to as printed or imitation batik. This consensus adhered to the regulations issued by the Indonesian Government, that a piece of batik is classified as genuine when hot wax is used during the production process, otherwise it is referred to as imitation batik.

Focus Group Discussion held on January 13, 2023 at Lasem, Central Java, Indonesia. The participants consisted of 15 Batik Entrepreneurs from Lasem. (Source, Author, 2023)

The statement also adhered to the Indonesian National Standard (0239:2014), which defined batik as a handicraft in which wax is applied to the fabric using a canting or stamping tool to create a meaningful motif (Affanti & Hidayat, 2019). Therefore, a textile product made with a printing machine cannot be considered as batik. In 2009, UNESCO categorized batik, a cultural heritage, into three groups, namely hand-drawn (canting batik), stamped (cap/block batik), and a combination of both (Nugroho, 2013). According to entrepreneurs, it would be preferable to use the products of Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats directly for fashion products.

Figure 29 shows the production process of Batik Tiga Negeri in Pleats, focused on modernity.

14. Conclusion

In conclusion, the transformation process of Batik Tiga Negeri, applied the ATUMICS method, which resulted in the production of contemporary concepts and artifacts. However, through experimental applications of this method, misconceptions about batik, considered an old artifact or tradition that struggled to adapt to modern times, was addressed. The ATUMICS method proved effective in appropriately producing new artifacts that maintained cultural values based on local wisdom and modernity. The concept was proven to be the most important element, as it was resilient in facing extinction. A strong and clear concept caused the transformation process to be more focused and responsive to the needs of contemporary society. This experiment resulted in three artifacts, Batik Tiga Negeri, with a contemporary integration of visual styles from three countries into a single design, a style with pleated or accordion texture, and the fashion application.

Academics, designers, and entrepreneurs had the opportunity to further analysis the results of this practice-based study to produce other similar artworks. It was anticipated that the younger generation would have been able to evaluate the development of alternative applications for contemporary batik designs and usage in fashion. This was expected to prevent the perception of batik as a meaningless old item, but rather as a cultural asset capable of developing alongside technological advances and maintaining relevance indefinitely.

Based on the results, these new concepts and artifacts offered several advantages:

1. The concept was applicable for development in the three countries, enriching the batik repertoire of each nation.

2. The transformation process maintained the sustainability of batik, and offered new alternatives for developing designs with contemporary values.

3. This concept could be applied in every region or country with a batik culture.

4. Economically, it helped batik entrepreneurs in developing new designs and accessing market opportunities.

5. It served as examples and directions to help the younger generation of batik artists or entrepreneurs experiment with developing new types of batik with modern values.

6. Provided new alternatives for developing batik applications in fashion

Notes

Copyright : This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted educational and non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- Achjadi, J., & Damais, A. (2006). Butterflies & Phoenixes: Chinese Inspirations in Indonesian Textile Arts. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions..

-

Affanti, T. B., & Hidayat, S. R. (2018). Batik Innovations in Surakarta Indonesia. Paper presented at the 3rd International Conference on Creative Media, Design and Technology (REKA 2018)..

[https://doi.org/10.2991/reka-18.2018.31]

- Asa, K. (2006). Batik Pekalongan dalam Lintasan Sejarah. Paguyuban Pecinta Batik Pekalongan..

- APPBI Official (Producer). (2022, November 26). ZOOM BATIKstorySeri-26 APPBI: Motif dan Ragam Hias Batik Kelantan [video] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Ko-9ZTOY-E&list=PLRsL_zIXCzsLUQ1rwq52ymbfMgSI0My3I&index=1&t=866s.

- bin Ghazali, A. Z. (1978). Bunga Emas: Satu Tinjauan Dalam Hubungan Terengganu––Siam. Malaysia In History, 21(1), 32-37..

- Britannica. (n.d.). M. C. Escher. Brittanica.com biography. Retrieved Augustus 23, 2023 from https://www.britannica.com/biography/M-C-Escher.

- Crill, R. (2008). Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West. London: V&A Publishing, Victoria and Albert Museum..

- Elliott, I. M. (2004). Batik: fabled cloth of Java. Singapore: Periplus Edition..

- Gluckman, D. C., Muddin, S., & Petcharaburanin, P. (2019). A Royal Treasure: The Javanese Batik Collection of King Chulalongkorn of Siam. Bangkok: River Books..

- Hall-Duncan, N. (2022). Art X Fashion: Fashion Inspired by Art. National Geographic Books..

-

Huang, T. (2021). Idea Exchange in The Pleats–The Pleating Workshop as a Research Method. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology, 7(4)..

[https://doi.org/10.33552/JTSFT.2021.07.000667]

- Indarmaji. (1983). Seni Kerajinan Batik. Yogyakarta: Dinas patiwisata Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta..

- Joneurairatana, E. (2021). Art and Design Research. Thailand: Ph.D. Design Arts, International Program Faculty of Decorative Arts, Silpakorn University..

- Kalajian, L., Kalajian, G., & Sauma, J. (2017). Pleating: Fundamentals for Fashion Design. Schiffer Fashion Press an Imprint of Schiffler Publishing, Ltd..

-

Kari, R., Samin, A., & Legino, R. (2019). The Sustainability's Motif and Design of Fauna in Malay Block Batik. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the first International Conference on Social Sciences, Humanities, Economics and Law, September 5-6, 2018, Padang, Indonesia..

[https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.5-9-2018.2281088]

- Kebaya Societé [kebayasocieté] (2023, February 20). Kain Wiron (Lipat) [Instagram Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/Co3qa6ShzOA/?img_index=1.

- Laksmi, V. K. P. (2010). Simbolisme Motif Batik Pada Budaya Tradisional Jawa dalam Perspektif Politik dan Religi [The symbolism of Batik Motifs in Traditional Javanese Culture in Political and Religious Perspectives]. Jurnal Ornamen, 7(1), 73-84. http://repository.isi-ska.ac.id/2036/.

-

Li, X. (2023). Research on Marketing and Business Operation of Second-tier Luxury Brands and Analysis of Development Limitations-A Case Study of Issey Miyake. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences, 53, 307-312..

[https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/53/20230860]

-

Lukman, C. C., Rismantojo, S., & Valeska, J. (2022). Komparasi Gaya Visual dan Makna pada Desain Batik Tiga Negeri dari Solo, Lasem, Pekalongan, Batang, dan Cirebon. Dinamika Kerajinan dan Batik: Majalah Ilmiah 39(1), 51-66..

[https://doi.org/10.22322/dkb.v39i1.6447]

- Malagina, A. (2018, Februari). Adiwastra Tiga Negri. National Geographic Indonesia, 14, 22-39..

- Miyake, I., & Kitamura, M. (2012). Pleats Please. Taschen. Monteil, E. (2017, February 10). Introduction to Lai Thai (Traditional Thai Art). Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@eric.monteil/introduction-to-lai-thaitraditional-thai-art-4fcc2f68879b.

-

Muneenam, U., Suwannattachote, P., & Mustikasari, R. S. (2017). Interpretation of Shared Culture of Baba and Nyonya for Tourism Linkage of Four Countries in the ASEAN Community. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 38(3), 251-258..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2016.08.015]

- Muzium Negara. (n.d.). Bunga Mas (Golden Flower). In (pp. Infographic). Galeri C: Era Kolonial: Muzium Negara Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia..

- Nugraha, A. (2012). Transforming tradition: A method for maintaining tradition in a craft and design context . (Doctor's degree). Aalto University, Helsinki. Retrieved from http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:aalto-201604111722.

- Nugraha, A. (2019). Perkembangan Pengetahuan dan Metodologi Seni dan Desain Berbasis Kenusantaraan: Aplikasi Metoda ATUMICS dalam Pengembangan Kekayaan Seni dan Desain Nusantara. Paper presented at the Seminar Nasional Seni dan Desain 2019..

- Nugroho, P. (2013). A socio-cultural dimension of local batik industry development in Indonesia. Paper presented at the 23Rd Pasific Conference of The Regional Science Association International (RSAI) and the 4th Indonesian Regional Science Association (IRSA) Institute, Bandung, Indonesia..

- Parmono, K. (1995). Simbolisme Batik Tradisional. Jurnal Filsafat, 1(1), 28-35..

- Parmono, K. (2013). Nilai Kearifan Lokal dalam Batik Tradisional Kawung. Jurnal Filsafat, 23(2), 134-146..

- Perbadanan Kemajuan Kraftangan Malaysia. (1981). Serian Batik . Kuala Lumpur: Cetakan Bahagian Daya Cipta..

- Pujiyanto. (2010). Estetika Spiritual Batik Keraton Surakarta. In M. Sutrisno, J. Sumarjo, M. Ali, G. Simatupang, R. Widayat, P. Pujiyanto, & S. Marwati (Eds.), Prosiding Seminar Nasional Estetika Nusantara (pp. 108-126). Surakarta: ISI Press untuk Program Pascasarjana ISI Surakarta..

- Rismantojo, S. (2021). Peranakan Batik: Cultures Connection in Indonesia, Malay Peninsula, and Thailand. The New Viridian Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(2), 57-72. Retrieved from https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/The_New_Viridian/article/view/245908.

-

Razali, H., Ibrahim, M., Omar, M., & Hashim, S. (2021). Current Challenges of The Batik Industry in Malaysia and Proposed Solutions. Paper presented at the AIP Conference Proceedings..

[https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0055651]

-

Rizali, N. (2018). Elements of Design in Batik Tiga Negeri, Lasem. Paper presented at the 2018 3rd International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (ICESAME 2018)..

[https://doi.org/10.2991/amca-18.2018.29]

- Roojen, P. V. (2001). Batik Design. Singapore. The Pepin Press..

- SACIT (The Support Arts and Crafts International Centre of Thailand). (n.d.-a). The Batik Textile: Krabi Province..

- SACIT (The Support Arts and Crafts International Centre of Thailand). (n.d.-b). Types of Handicrafts: Batik..

- Saidon, M. K. K., & Shuib, A. S. (2017). Sepintas Lalu Melihat Aspek Bunga Mas Kerajaan Negeri Setul dan Perkaitan Dengan Sejarah Kedah dalam Era Penguasaan Siam. Paper presented at the National Conference on Social Science, Education, Engineering and Technology Langkawi. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319928304_SEPINTAS_LALU_MELIHAT_ASPEK_BUNGA_MAS_KERAJAAN_NEGERI_SETUL_DAN_PERKAITAN_DENGAN_SEJARAH_KEDAH_DALAM_ERA_PENGUASAAN_SIAM.

-

Sari, I. P., Wulandari, S., & Maya, S. (2019). Urgensi Batik Mark Dalam Menjawab Permasalahan Batik Indonesia (Studi Kasus di Sentra Batik Tanjung Bumi). Universitas Indraprasta PGRI, 11(1), 16-27..

[https://doi.org/10.30998/sosioekons.v11i1.2932]

- Smanchat, S. (2021). Ayutthaya Textile - Pha Lai Yang: Artistic Heritage of Ayutthaya. Phranakhon Si Ayutthaya: Committee of University Affairs, Phranakhon Si Ayutthaya Rajabhat University, Ayutthaya Studies Institute, Phranakhon Si Ayutthaya Rajabhat University, and Ayutthaya Provincial Culture Council..

- Suriastuti, M. Z., Wahjudi, D. and Handoko, (2014). Kajian Penerapan Konsep Kearifan Lokal Pada Perancangan Arsitektur Balaikota Bandung. Jurnal Itenas Rekarupa, 2(1), 122-128..

-

Sutrisno, A. (2020). Transforming the Traditional Engklek Game Using ATUMICS Method. KnE Social Sciences, 640-650..

[https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v4i12.7638]

- Tirta, I. (1996). Batik: A Play of Light and Shades. Jakarta: PT Gaya Favorit Press..

- Veldhuisen, H. C., Setiadi, A., & Laksono, D. (2007). Batik Belanda 1840-1940: Pengaruh belanda pada batik dari Jawa sejarah dan kisah-kisah di sekitarnya. Gaya Favorit Press..

- Yunus, N. A. (2011). Malaysian Batik: Reinventing a Tradition. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing..