Unveiling Gender Differences in Visual Metaphor Interpretation in Indian Banking Print Advertising

Abstract

Background In today’s modern world economy, businesses and financial institutions often use advertisements to attract customers and to establish brand image. Print ads are one of the important sources of disseminating information, especially in India’s banking sector. However, little is known about gender preferences and their impact on Indian banking print advertisements. Exploring visual metaphors in banking print ads is crucial to understanding interpretation1) patterns and inferences among genders, enabling designers to create more effective ads. The current paper aims to elucidate the exploration of the interpretation of both genders (male and female) towards the banking print ads ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’. The insights gained would further help potential designers know about the preferences and likes of people across genders and use that information to create ads more effectively.

Methods A three-month online survey was conducted on 102 participants (51 males and 51 females) to gather data on their interpretations of ads related to car loans, education loans, and fixed deposits in the banking sector. The data was analyzed quantitatively using independent t-tests for ‘advertisement liking’ (‘ad-liking’) and qualitatively using the content analysis approach to gather inferences.

Results Quantitative analysis showed that the use of ‘visual metaphors’ in banking product ads affected mean scores differently across genders. Females consistently scored higher in ads ‘with visual metaphors,’ while males showed greater variability. However, the difference between groups ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’ was not substantial. Further qualitative analysis was needed to determine if any differences lie in interpreting ads by participants from both genders.

The results of the qualitative study signify the thematic resonance between the male and female psyche in advertisements. Males, traditionally family breadwinners, portrayed finance and analytics themes more pragmatically. Conversely, females displayed a broader analytical attitude and emotional depth, engaging with the advertisements beyond the financial narrative. Their indirect linkage of education with freedom and opportunity portrayed aspiration and empowerment, reflecting societal demand for change.

Conclusions This study uses visual metaphor-based ads and non-metaphor-based ads to examine the design and reception of advertisements in the banking sector. The study highlights the need for advertisers to create messages that resonate on multiple levels, transcending traditional gender roles. The insights inform marketers to create advertisements that capture attention, inspire change, and resonate with human aspirations, ultimately boosting sales and revenue. The study provides a preliminary understanding and encourages further, more in-depth research on the topic in the future.

Keywords:

Visual Metaphor Studies, Advertisement Research, Banking Product Advertisement, Gender Preferences, Visual Studies, Brand image1. Introduction

India’s banking sector has a massive arena of public and private brands serving close to a billion people (Singh & Milan, 2023), and it forms a premise of a competitive landscape, where attracting and retaining customers is most important. In this context, advertising plays a crucial role, with banks allocating significant resources to print and online campaigns to gain a competitive advantage over the other brands. While logos, visual symbols, and value communication have been individually explored in banking advertising, the intricate use of visual metaphors remains unexplored. Foroudi et al. (2014) and Guo (2017) highlighted the influence of logos and culturally-aligned visuals on customer perception. In banking advertisements, advertisers use visual symbols and visual metaphors. A visual symbol is an image, icon, or graphic representing an idea, concept, object, or action, conveying clear messages quickly and efficiently without words. Visual symbols are powerful because they transcend language barriers, providing a universal form of communication. It is widely used in art, literature, branding, signage, and communication (Latała-Matysiak & Marciniak, 2021; García-Peñalvo et al., 2012). Visual metaphor, or pictorial metaphor, develops when an image represents a notion or concept that is distinct from its literal representation. It entails using visual components to communicate intangible ideas or connections. Visual metaphors are powerful tools in communication since they can elicit emotions, clarify complex concepts, and improve comprehension via the use of imagery (Indurkhya & Ojha, 2017). The design process of visual metaphor plays a crucial role in creating distinct and engaging messaging that often employs the art of the metaphor (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004). Amidst this pool of campaigns, visual metaphors emerge as a powerful tool that transfers features of one thing onto another, even if they seem dissimilar (Sopory & Dillard, 2002). Visual metaphors have gained significant attention in advertising studies throughout the years (Huang, 2023; Hatzithomas et al., 2021; Margariti et al., 2021; Huang, 2020; Lagerwerf et al., 2012; Gkiouzepas & Hogg, 2011; Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004, 2002).

Despite the hefty budgets banks use for advertising (Nethala et al., 2022), there is a dearth of research on the impact of visual metaphors in print advertisements concerning gender within the Indian context and the global context. Presently, a limited number of available articles explore the use of visual metaphors in banking and financial advertisement (Das et al., 2023). The importance of visual metaphor in advertisement design and the lack of studies on the impact of visual metaphor highlights the need for comparative practices between different cultural contexts and the semiotic strategies employed in banking advertising (Yu, 2011; Bargenda, 2015). Thus, this study aims to understand how visual metaphors are being perceived by both genders, this study could serve as the primary understanding of how visual metaphors can be used as visual communication strategies for the banking sector.

2. Literature Review

The present research acknowledges the limited study in this domain and highlights the potential significance of investigating this intersection of visual metaphors and print advertisement of banking and finance. The following sections of this article serve as a base for the research, providing the current knowledge scenario in the domain.

2.1. Visual Metaphors in Advertising

Visual metaphors in advertising are essential for conveying complex messages to consumers. These metaphors utilize visual elements to represent abstract concepts, establishing a connection between the image and the intended message (Ang & Lim, 2006). By artfully deviating from viewers’ expectations, metaphors give ads a potent duality while conveying practical information and captivating imaginations (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009). Prior research indicates that visual metaphors in advertising can be more effective in generating positive outcomes than verbal metaphors (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009). According to Mulken et al. (2010), using visual metaphors in advertising can potentially improve understanding and appreciation. However, the perception of these metaphors varies depending on their complexity, variation, and comprehension in different nations. Jeong (2008) investigates the persuasive impact of visual metaphors in advertising, specifically exploring whether these effects come from visual reasoning or metaphorical rhetoric. Scott (1994) emphasizes the need for a theory of visual rhetoric in advertising to understand the persuasive influence of visual aspects. In addition, Zhao & Lin (2019) examine the influence of visual metaphors on advertisement reaction, emphasizing the persuasive power of visual rhetoric. Furthermore, Forceville (2007) examines imaginative advertising metaphors that combine words, visuals, and non-verbal elements to improve communication and create influence. This effect shows the complex interplay between several modalities in efficiently communicating information. This highlights that visual metaphor plays a significant role in the context of advertisement. However, the use of visual metaphors in the context of Indian banking print advertisements is underexplored, especially when it has already been established that gender has an important role to play in the interpretation of these metaphors.

2.2. Gender Roles in Interpreting Advertisement

Gender roles in advertisements have been extensively researched. Prior research shows that there is a considerable gender difference in the way that individuals process information and respond to advertisements (Das & Majhi, 2021; Booth & Nolen, 2012; Graham et al., 2002). It is suggested that both males and females possess the capacity to comprehend social clues to the same degree. However, differences arise in the degree to which they respond to these cues, with women being more vulnerable to their influence (Venkatesh et al., 2000). Moreover, a proposition has been made suggesting that women are more inclined to systematically evaluate the content of an advertisement when presented with comprehensive information. At the same time, males prefer to analyze advertisements using heuristics (Boshoff & Toerien, 2017). Gender and language theorists have generally supported the sex-role socialization model, which affirms that gender identity development occurs in early childhood within familial or same-sex peer groups. They also suggested and highlighted that gender roles influence language practices to a great extent (Carter, 2014). Sczesny et al. (2016) study examines gender variations in language usage, which has shown that using gender-fair language may effectively decrease gender stereotyping and discrimination (Sczesny et al., 2016). Furthermore, Furnham & Paltzer (2010) in their study reported that cultural backgrounds, age groups, and genders impact audience responses to gendered commercials.

In the Indian context interpretation of advertisements by males and females is influenced by the determination of gender stereotyping in media. Kumari & Shivani (2014) highlight the continuing dependence on traditional gender tropes in marketing communication, which reinforces existing biases and expectations. This practice affects how males and females see advertisements, often perpetuating traditional roles and behaviours. Chitra (2023) shows concern in her study of the gender imbalance in children’s television advertising in India, showing how early exposure to such content can shape young minds. Boys and girls may develop different sensitivities to their roles and capabilities, influenced by the stereotypical representations they encounter. Indumathi & Nivedhitha (2017) emphasize the reinforcement of traditional gender roles in Indian advertisements, suggesting that these societal norms impact the interpretation of ads by both sexes. However, Pathak (2024) and Barthwal (2023) note a shift towards more professional and empowered representations of women, reflecting changing societal dynamics. While women might feel empowered and validated by these evolving portrayals, men may view them as either a reflection of progress or a challenge to traditional roles. This evolving landscape in advertising highlights the complex and dynamic nature of gender interpretations in media. However, a lacuna has been observed in the domain of visual metaphor interpretation through the gender perspective in the Indian context. Therefore, the present study focuses on comprehending different gender interpretations of banking print advertisements: ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’ to gain valuable insights.

2.3. Indian banking sector

There is a lack of exploration in the domain of aesthetics in banking print advertisements, with various gaps in the literature. However, logos, emotional appeal, and value communication (Wilson, 2021; Czarnecka & Mogaji, 2020) have been separately explored in banking print advertising. Interestingly, the use of visual metaphors remains unexplored.

The Indian banking sector has undergone significant changes over the years, switching from private to public and again to private ownership (Sathye, 2010). Due to this change, the competitive environment is now marked by monopolistic competition. As a result, this sector has shifted towards human-centric design aspects, such as user (customer) satisfaction and loyalty, which nowadays have become much more essential than service quality’s critical aspects comprising technical and tangible factors (Lenka et al., 2009). Additionally, the effectiveness of advertising in Indian banks has been a subject of study, focusing on comparative analysis between private and public sector banks (Mulchandani et al., 2019). Furthermore, the impact of brand value on the financial performance of banks has been empirically studied, which indicates a growing realization among Indian banks that business success depends on user service and satisfaction (Arora & Chaudhary, 2016).

In the visual communication design context, examining brand models and their correlations with user preferences regarding banking products has been highlighted as an area for further examination (Gombos & Bíró-Szigeti, 2023). Srivastava & Dey (2016) examined brand analysis of global and local banks in India has revealed the coexistence of significant players in the banking industry, suggesting the need for a nuanced approach to visual communication design that caters to diverse consumer segments. However, scanty research relating to banking print advertisements focuses on determining the role and use of visual metaphors in conveying complex financial concepts and shaping brand relationships with the target customers within the banking sector, especially from the gender perspective.

An examination of Indian banking print advertisements from the perspective of visual communication is essential due to the distinct features specific to the Indian context that differentiate it from other countries. Advertising tactics and customer perceptions in India are shaped by unique cultural traits (Limbu, 2024). The diverse linguistic and cultural customs in India influence the visual communication strategies used in advertisements, highlighting the importance of understanding these nuances for effective communication (Cayla & Elson, 2012). Moreover, the attention towards the Indian financial sector is crucial as financial literacy is not included in high schools in India and is later introduced (Jayaraman & Jambunathan, 2018). Apart from this, financial literacy in the Indian context also has a relation with gender where women are supposed to know less than men about a variety of financial products and procedures (Rink et. al, 2021). Another study by Banerjee & Roy (2020) found the top Indian literate states of Kerela, where the financial literacy level of women remains lower compared to men. Mohammed et al.’s (2020) study defines a rational reason for males’ better understanding of financial instruments and practices. This shows that India presents a unique landscape in the domain of visual communication and understanding the banking print ads could help to expand knowledge in visual communication and also could contribute to financial literacy in the later stages.

2.4. Research Questions

It is evident from the literature that a research gap lies in understanding the impact of visual metaphors on gender, especially in the Indian banking and finance context. This research aims to identify the difference in interpretation and engagement of the gender ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’ print advertisements for banking services in India. The research attempts to answer the following research question:

What are the similarities and dissimilarities between the responses of male and female participants for the banking print advertisements of India ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’?

3. Methodology

This research takes a positivist stance towards the research question, stating that the answer to the research question exists among the people, especially those targeted by the advertisements’ designers. The following sections elaborate on the different methods used to gain information from the people.

3.1. Participant Selection and Demographic Profile

The snowball sampling was adapted to collect the data through Google Forms. Snowball sampling is a recruiting strategy that involves encouraging current participants to suggest others from their social network to participate in the study. This allows researchers to get access to the social circles of the participants and engage themselves in their social networks (Shepherd et al., 2020). In this study, the participants were gathered through an online survey spread via Google Forms, which remained open for three months. The link to the Google form was disseminated through two social media platforms - WhatsApp, and Facebook Messenger. In India, discussions about financial matters are often considered private and sensitive (Mahapatra et al., 2016). Due to this reason, people hesitate to participate in bank-related activities organised by third parties. Hence, a lower participation rate was expected. A total of 109 participants responded. However, 7 participants did not complete the form. 102 responses (51 males and 51 females) were used for the study with the mean age of participants as 28.4 years.

The participants in this study were university students from various institutions across India such as Jawaharlal Nehru University covering the northern part of India, University of Calcutta and Jadavpur University covering the eastern part of India, Guwahati University, and Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati covering the northeast part of India, and finally, University of Hyderabad covering the southern part of India. All the universities include students from all over the country. However, the state universities (University of Calcutta, Jadavpur University, Guwahati University) have 90 per cent reservation for students of their own state, while the other universities such as central universities (Jawaharlal Nehru University and University of Hyderabad) and institutes of national importance (Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati) maintain an ethnographical diversity. The inclusion criteria for the study focused on age, with participants ranging from 20 to 40 years old. This age range was selected to capture a diverse set of perspectives and experiences, reflecting both younger and more mature student demographics. According to Xiao et al., (2020) college graduates are more likely to display numerous financial behaviours compared to college enrollees and dropouts. In the Indian context, there has been a dearth of financial education at the school level (Jayaraman & Jambunathan, 2018). Hence, the educational qualifications of participants were also considered significant for the survey, with all respondents having completed at least a bachelor’s degree, spanning various fields of study (Cao et al., 2020).

3.2. Selection of Stimuli

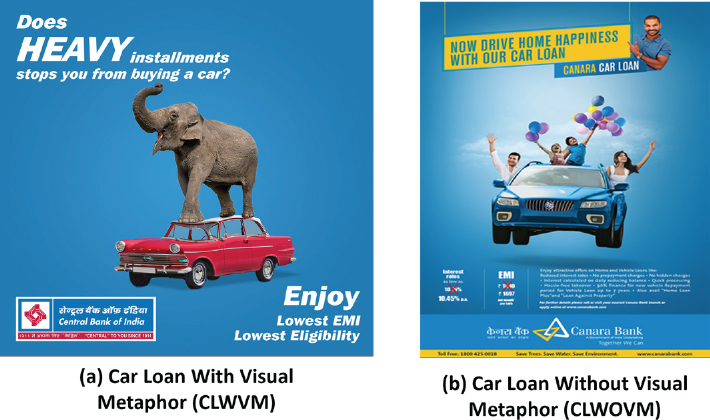

Since the study focuses on banking print advertisements, the images sourced from popular Indian magazines such as India Today, Outlook, and The Week, spanning the last five years (2017-2022), as shown in Figures 1,2,3.

To ensure the appropriate selection of images ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’, two experts were employed. The experts were selected based on the inclusion criteria of at least six years of experience in design. The first expert has been working as the creative director of Interactive Avenues - one of the leading advertising agencies in India for the last 7 years. The second expert is an assistant professor at the Department of Design in Kala Bhavan in Visva Bharati University with over six years of experience in visual communication research. The experts selected advertisements based on their extensive knowledge and mutual discussion. The selection parameters focused on the strength of metaphors in the advertisements, evaluating whether the ads contained metaphorical clues and to what degree these clues were present. For advertisements without metaphors, the clarity of the message was the primary consideration. The Experts reviewed 30 advertisements, 15 featuring ‘with visual metaphors’, and 15 ‘without visual metaphors.’

The selection was eventually narrowed down to six advertisements through iterative review. These included a pair of ads comprising ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors.’ These pairs included car loan ads, education loan ads, and fixed deposit ads, which play a significant role in the banking industry. These themes were selected as previous research on banking-related products has highlighted that loans are a lifeline for numerous students pursuing professional courses (Pant et al., 2021). Similarly, allocating bank loans to specific sectors, such as the automotive and real estate industries, is essential for economic growth and development (Hacievliyagil & Ekşi, 2019). The following figures (Figure 1 a), b), Figure 2 a), b) and Figure 3 a), b) illustrate these ads ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’ for the car loan, education loan, and fixed deposit, respectively.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were collected through an online survey to obtain both quantitative and qualitative insights. The content analysis method (Nelson & Paek, 2007; Hetsroni & Tukachinsky, 2005) was deployed to identify prevalent themes and words within the data, quantifying the occurrence of coded themes, followed by comparative analysis (Dall’Olio & Vakratsas, 2023) to explore similarities and differences in responses between genders and among the different types of advertisements. The coding process was conducted using ATLS.ti 24 software. A 7-point Likert scale on liking (‘1’ being least liked and ‘7’ being most liked) was used to obtain the data on respondent’s “ad-liking” towards the ads. An independent t-test was performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 22 to observe if there were statistically significant changes between the means of two separate groups.

4. Result & Discussion

The result of the study is presented in two parts. The first part depicts the statistical test result of the liking rating, and the second part reflects the content analysis results.

4.1. Statistical analysis of ad-liking

The data elucidated details regarding the mean scores, standard deviations (SD), and standard errors of the mean (SEM) for responses gathered related to visual metaphors in images concerning car loans (CL), education loans (EL), and fixed deposits (FD). These responses are grouped by gender categorization.

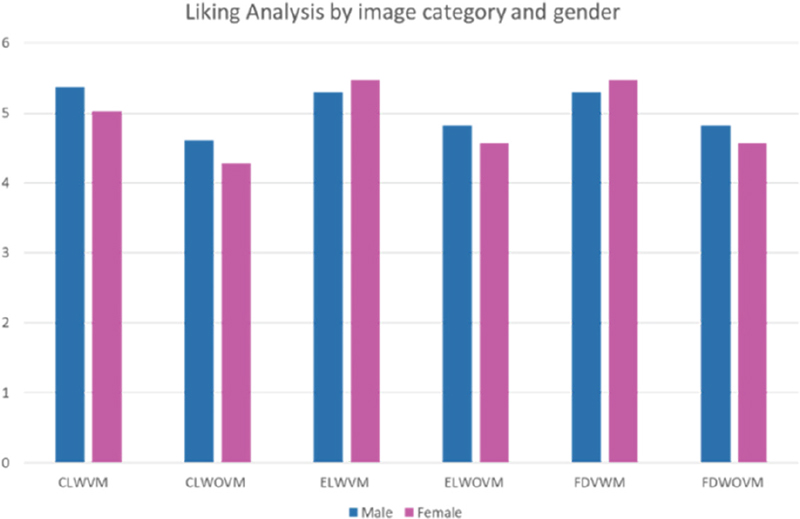

Pertaining to ads for car loans, the data indicates that males exposed to ads for car loans ‘with visual metaphor’ (CLWVM) reported a higher mean score (M = 5.372, SD = 0.915, SEM = 0.128) compared to females (M = 5.019, SD = 1.655, SEM = 0.231). Similarly, for the car loan ad ‘without visual metaphors’ (CLWOVM), males exhibited a lower mean score (M = 4.607, SD = 1.844, SEM = 0.258) than females (M = 4.274, SD = 1.898, SEM = 0.265).

Concerning the ads for education loans, males ‘with visual metaphors’ ads (ELWVM) indicated a mean score of 5.294 (SD = 1.540, SEM = 0.210), whereas female audience scored slightly higher (M = 5.470, SD = 1.63, SEM = 0.231). For the education loan ads ‘without visual metaphors’ (ELWOVM), males scored a mean score of 4.823 (SD = 1.492, SEM = 0.209), and females fetched a mean score of 4.568 (SD = 1.565, SEM = 0.219).

In the context of ads related to fixed deposits, males ‘with visual metaphors’ (FDWVM) exhibited a mean score of 5.294 (SD = 1.540, SEM = 0.164). However, females ‘with visual metaphors’ showed a mean score of 5.470 (SD = 1.653, SEM = 0.175). Interestingly, for ads ‘without visual metaphors’ (FDWOVM), both males and females exhibited lower mean scores of 4.823 (SD = 1.492, SEM = 0.202) and 4.568 (SD = 1.565, SEM = 0.197), respectively. Figure 5 illustrates the graphical representation of the data discussed above.

Analysis of Male vs. Female Interpretations of Advertisement Content ‘With Visual Metaphor’ and ‘Without Visual Metaphor’

From the analysis of the presented data, it can be inferred that the presence of visual metaphors administered a varying impact on the mean scores across different banking product ads. Females have depicted a consistently higher mean score in the presence of visual metaphors across all categories of banking product-related ads. In contrast, the males’ scores exhibited a greater variability. However, the difference in mean scores between the groups ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’ is not substantial in any categories. Thus, there is a need to analyze the data further from a qualitative perspective to determine whether any difference lies in the interpretation of the ads being viewed ‘with visual metaphors’ and ‘without visual metaphors’ by the participants from both genders.

4.2. Content analysis

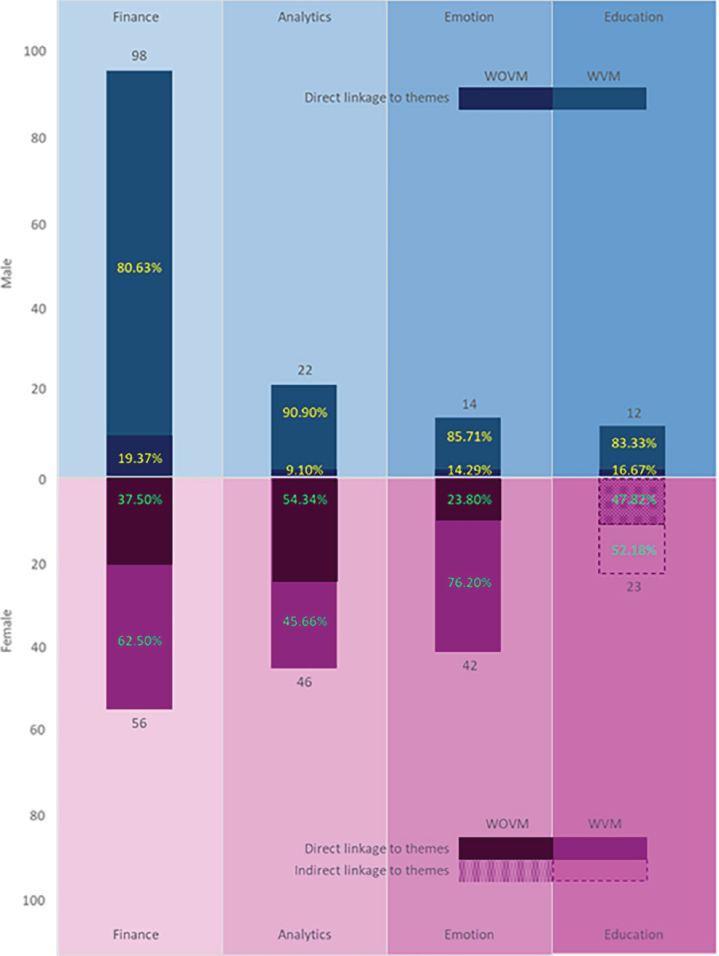

In the purview of the content analysis of the participant responses (both genders), the four major themes emerged: finance, analytics, emotion, and education. Table 1 shows the process of emerging themes from codes. Two different types of themes regarding education emerged.

The first was education, where the participants directly referenced the context of education. The second theme that emerged that was related to education was termed the indirect concept of education as these respondents instead of having a direct reference to education made an indirect comparison of education such as empowerment, freedom, etc. Figure 5 shows the analysis of male and female interpretations of advertisement content ‘With Visual Metaphor’ and ‘Without Visual Metaphor’.

While analyzing the female responses, it was observed that instead of using indirect linkage with the theme of education, female participants used indirect linkage codes like freedom, opportunity, liberty, ‘empowerment’, fly, and fulfilment.

In the case of male participants, the distribution of coded themes (finance, analytics, emotion, and education) was uneven, as shown in the Figure. 5. Male participants gave more importance to finance, with an occurrence of 98 times (67.12% of total male-coded concepts), followed by analytics, with the occurrence of 22 times (15.06% of total male-coded concepts), followed by emotion, an occurrence of 14 times (9.58% of total male coded concepts), and lastly education with the occurrence of 12 times (8.23% of total male coded concepts). On the other hand, the responses of the female participants showed different frequencies, with finance with the occurrence of 56 times (38.88% of total female-coded concepts), followed by analytics with the occurrence of 46 times (31.94% of total female-coded concepts) and followed by emotion with the occurrence of 42 (29.18% of total female coded concepts). Lastly, no occurrence was found regarding the education theme among the female participants. Instead, they gave responses in the form of indirect linkages words, as discussed above.

The finance theme contains 80.86% of the coded concepts from the advertisement ‘with metaphor’ and 19.37% of the coded concepts ‘without metaphor’ by male participants. In contrast, the occurrence of female participants was 62.50% ‘with metaphor’ and 37.50% concepts ‘without metaphor.’ In this case, 90.90% of the coded concepts were from the advertisement ‘with metaphor,’ and 9.10% were from ‘without metaphor’ by male participants. However, female participants showed a different trend, where 45.66% were ‘with metaphor’ and 54.34% were ‘without metaphor.’ The emotional theme showed a similar trend with finance, where 85.71% of the coded concepts from the advertisement were from ‘with metaphor’ and 14.29% of the coded concepts were from ‘without metaphor’ by male participants. The occurrence of female participants was 76.20% ‘without metaphor’ and 23.80% ‘without metaphor’ by female participants. A similar trend was also found in the education theme, where 83.33% of the coded concepts from the advertisement were from ‘with metaphor’ and 16.67% of the coded concepts were from ‘without metaphor’ by male participants. The occurrence of female participants was 52.18% from ‘with metaphor’ and 47.82% from ‘without metaphor.’

The purpose of the study was to find the similarities and dissimilarities between the responses of male and female participants for the banking print advertisements of India ‘with metaphor’ & ‘without metaphor.’ Fenko et al. (2018) and Zaho and Lin (2019) suggested that there may be differences in how males and females process visual information, which could extend to the interpretation of visual metaphors. These studies, however, could not answer the difference between their responses, and it is unsure if it can also be extended to a specific context and category of advertisement. The current study uses three banking advertisements to explore the difference between the responses of genders. It collects survey responses of both genders on their liking of the advertisement and interpretation of the ads. The study shows that both genders prefer advertisements ‘with visual metaphors’ to advertisements ‘without visual metaphors.’

However, the visualization of the liking analysis in Figure 4 shows that there is not much variation in liking advertisements by both genders. Hence, content analysis was used to identify if there were any differences between the interpretations of the genders.

Analysis of Male and Female Liking ‘With Visual Metaphor’ and ‘Without Visual Metaphors’ Advertisements

The content analysis revealed that in the case of the finance theme, the occurrence of coded concepts was higher in male participants’ comments. While this observation supports the prevailing view that males are more attuned to financial matters and respond more quickly due to traditional financial responsibilities in Indian society (Rink et al., 2021; Banerjee & Roy, 2020; Mohammed et al., 2020), it also highlights the need for further exploration to understand the exact rationale behind this trend. In the instance of the analytical theme, women were found to respond to the advertisement with greater analytical ability. This conclusion is consistent with Ruhina & Sridevi’s findings (2021), which revealed that women outperformed men in phonemic verbal skills and picture recognition tests. The study also found that women performed better regarding cognitive processes and visual depth perception. Females are considered more emotional compared to their male counterparts, which is reflected in the result of the content analysis of the present study, where themes of emotion were more prevalent among the female participants. A previous study also showed that females outperformed males in emotional information processing (Chen X et al., 2018). The result of the content analysis initially showed that females did not mention education in the comments, which was unlikely. A re-evaluation of the content revealed that female participants linked education with themes like fly, freedom, opportunity, etc. They are more focused on their freedom of choice of settling their own life without social pressure. They found education as an opportunity to break the barriers of society. According to Nirui Si (2022), all over Asia, female literacy rates are the lowest in India due to a lack of emphasis on it. It might have resulted in a difference in interpreting the education loan advertisement.

A few general observations regarding the style and stature of participants’ answers (responses) were also noted while scrutinizing the participants’ responses. Most male participants used long sentences to interpret the advertisement and express their approach toward its narrative. In contrast, female participants mainly used short sentences to interpret the ad, and female participants tried describing their responses more explicitly (expressing emotions using few words). In some cases, female participants interpreted the metaphor of the advertisement literally (word-to-word meaning); they were not very interested in decoding the meaning. The participants of both genders mainly concentrated on the visual part of the ads. There is some agreement between this result and that of Hutton and Nolte (2011), who highlighted the significance of visual elements in capturing viewer attention and supporting the idea of focusing on appropriate images to communicate messages in advertisements effectively. Moreover, the present study also observed that only when the participants were having trouble understanding the advertisements, did they try to find and read the text. For this sake, they tried searching for clues in the ad’s text. Even after doing so, if they still fail to understand it, their attitude turns negative/indifferent towards the ad. It may be because they feel deceived and think that they are not capable of grasping the ad’s meaning.

5. Conclusion

The revelations of this study on the impact of visual metaphors in banking advertisements in India present several insights into gender-based interpretations and preferences. The statistical analysis laid the foundation by highlighting a unanimous inclination towards advertisements ‘with visual metaphors’ across genders, though the degree of liking varied minimally. It revealed that ads ‘with visual metaphors’ were attractive and more engaging. In addition, such ads ‘with visual metaphor’ also hint at deeper meanings worth looking into.

In reference to the inferences drawn from the content analysis, the current study explored distinct thematic resonance with the male and female psyche. Males, anchoring in the traditional role of family breadwinners, resonated more with themes of finance and analytics, embodying a pragmatic approach to the advertisements. Conversely, females exhibited a broader analytical attitude and emotional depth, reflecting a nuanced engagement with the advertisements beyond the surface-level financial narrative. Their indirect linkage of education with themes of freedom and opportunity painted a picture of aspiration and empowerment, echoing a societal demand for change.

The divergent paths in theme engagement between genders underscore a profound insight: advertisements, especially those ‘with visual metaphors,’ are not merely captivated; they are experienced and interpreted through the lens of societal roles, personal aspirations, and cognitive predispositions. The male audience’s preference for finance and analytics and the female’s inclination towards emotional depth and aspirational themes highlight the multifaceted nature of advertisement interpretation and show the normative roles of the genders. This research findings are in line with Venkatesh et al., (2000) which mentions that there are differences in the degree to which the genders respond to the cues. The research also identified the minute differences that the designers can use to design advertisements that can target specific genders.

To conclude, this study looks into the banking sector’s advertisement design and subsequent audience reception (through visual metaphors and non-metaphor-based ads). It further attempts to mirror the evolving societal constructs that shape gender interpretations. The subtle yet significant differences in thematic engagement highlight the need for advertisers to craft messages that resonate on multiple levels, transcending traditional gender roles to connect on a more human and universal scale.

Moreover, in a world where advertisements are not just seen but felt, the insights that emerged from this study inform marketers and designers to delve deeper into the psychological realms of their audience, creating advertisements that not only capture attention but also kindle the imagination, inspire change, and resonate with the core of human aspiration. The novelty of this study lies in understanding and providing a basis for future explorations into the intricate interaction between visual metaphors and the human psyche.

6. Limitations and Future Scope

This study delved into the complexities of visual metaphors in Indian banking print advertisements, underscoring their significance in conveying messages effectively. Despite careful assessment of the ads and logical steering of the study, the present study is deemed to have some limitations. The study did not consider the class differences based on respondents’ family income and educational qualifications. The respondents included the participants pursuing master’s degrees or Ph.D. Such participants remain well educated, which may introduce bias into the results. Future research should consider a more diverse sample, including different social classes, academic backgrounds, ethnicities, and ages, to gain broader insights. Additionally, the study found gender differences in the perception of finance-related matters, suggesting a valuable area for further research to explore the underlying reasons and enhance understanding in this field. Finally, the study recommended further investigation through two key approaches: conducting in-depth interviews with users for qualitative analysis and administering surveys with larger sample sizes for quantitative analysis.

Glossary

1) The process of understanding visual stimuli involves attributing meaning by taking into account context, prior knowledge, and viewpoints.

Notes

Copyright : This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted educational and non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

-

Ang, S. H., & Lim, E. A. C. (2006). The influence of metaphors and product type on brand personality perceptions and attitudes. Journal of advertising, 35(2), 39-53..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2006.10639226]

-

Arora, S., & Chaudhary, N. (2016). Impact of Brand Value on Financial Performance of Banks: An Empirical Study on Indian Banks. Universal Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 4(3), 88-96..

[https://doi.org/10.13189/ujibm.2016.040302]

-

Banerjee, T., & Roy, M. (2020). Financial literacy: an intra-household case study from West Bengal, India. Studies in Microeconomics, 8(2), 170-193..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/2321022220916081]

-

Bargenda, A. (2015). Sense-making in financial communication: Semiotic vectors and iconographic strategies in banking advertising. Studies in Communication Sciences, 15(1), 93-102..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scoms.2015.01.001]

-

Barthwal, S. (2023). Gender portrayals and perceptions in the new age society of India. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 31(1), 102-121..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/09715215231210530]

-

Booth, A., & Nolen, P. (2012). Salience, risky choices, and gender. Economics Letters, 117(2), 517-520..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.06.046]

-

Boshoff, C., & Toerien, L. (2017). Subconscious responses to fear-appeal health warnings: An exploratory study of cigarette packaging. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 20(1), 1-13. doi. Org/10.4102/sajems. v20i1.1630.

[https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v20i1.1630]

-

Cao, S., Wang, H., & Zou, X. (2020). The effect of the visual structure of pictorial metaphors on advertisement attitudes. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 10 (4), 1-60. doi: 10.5539/ijms.v10n4p60.

[https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v10n4p60]

-

Carter, M. J. (2014). Gender socialization and identity theory. Social sciences, 3(2), 242-263. doi.org:10.3390/socsci3020242.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3020242]

-

Cayla, J., & Elson, M. (2012). Indian consumer kaun hai? The class-based grammar of Indian advertising. Journal of Micromarketing, 32(3), 295-308..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146712442547]

-

Chen, X., Yuan, H., Zheng, T., Chang, Y., & Luo, Y. (2018). Females are more sensitive to opponent's emotional feedback: evidence from event-related potentials. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 275..

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00275]

-

Chitra, K. (2023). Gender representations and portrayal of adults in children's television advertising: content analysis of prime cartoon channels in India. Frontiers in Psychology, 14..

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1234678]

-

Czarnecka, B., & Mogaji, E. (2020). How are we tempted into debt? Emotional appeals in loan advertisements in UK newspapers. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38 (3), 756-776..

[https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-07-2019-0249]

-

Dall'Olio, F., & Vakratsas, D. (2023). The impact of advertising creative strategy on advertising elasticity. Journal of Marketing, 87(1), 26-44..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002224292210749]

-

Das, P., & Majhi, M. (2021). Gender role portrayal in Indian advertisement: A review. In: Ergonomics for design and innovation. HWWE 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Volume 391 (pp. 461-471). Cham: Springer International Publishing..

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94277-9_40]

-

Das, P., Singh, G., Banik, G., & Majhi, M. (2023). Creating a proxy advertisement for cognitive response evaluation in visual metaphor studies under advertisement research. In: Advances in design and digital communication IV. DIGICOM 2023. Springer series in design and innovation, Volume 35 (pp. 765-776). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-47281-7_62.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47281-7_62]

-

Fenko, A., Vries, R., & Rompay, T. (2018). How strong is your coffee? The influence of visual metaphors and textual claims on consumers' flavor perception and product evaluation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9..

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00053]

-

Forceville, C. (2007). Multimodal metaphor in ten Dutch TV commercials. Public journal of semiotics, 1(1), 19-51..

[https://doi.org/10.37693/pjos.2007.1.8812.]

-

Foroudi, P., Melewar, T. C., & Gupta, S. (2014). Linking corporate logo, corporate image, and reputation: An examination of consumer perceptions in the financial setting. Journal of Business Research, 67(11), 2269-2281..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.015]

-

Furnham, A., & Paltzer, S. (2010). The portrayal of men and women in television advertisements: An updated review of 30 studies published since 2000. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 216-236..

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00772.x]

-

García-Peñalvo, F., Pablos, P., García, J., & Therón, R. (2012). Using owl-visMod through a decision-making process for reusing owl ontologies. Behaviour and Information Technology, 33(5), 426-442..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2012.709538]

-

Gkiouzepas, L., & Hogg, M. K. (2011). Articulating a new framework for visual metaphors in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 40(1), 103-120..

[https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367400107]

-

Gombos, N. J., & Bíró-Szigeti, S. (2023). Examination of the Brand Archetypes of the Hungarian Retail Banking Sector and Their Correlations with Consumer Preferences Regarding Banking Products. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 31 (2), 120-134..

[https://doi.org/10.3311/PPso.19926]

-

Graham, J. F., Stendardi Jr, E. J., Myers, J. K., & Graham, M. J. (2002). Gender differences in investment strategies: an information processing perspective. International journal of bank marketing, 20(1), pp.17-26..

[https://doi.org/10.1108/02652320210415953]

-

Guo, L. (2017). Symbol Analysis of Financial Enterprises' Advertisements - A Case Study of Citibank. Cultura, 14(1), 81-87..

[https://doi.org/10.3726/CUL.2017.01.08]

-

Hacievliyagil, N., & Ekşi, İ. (2019). A micro-based study on bank credit and economic growth: manufacturing sub-sectors analysis. South-East European Journal of Economics and Business, 14(1), 72-91..

[https://doi.org/10.2478/jeb-2019-0006]

-

Hatzithomas, L., Manolopoulou, A., Margariti, K., Boutsouki, C., & Koumpis, D. (2021). Metaphors and body copy in online advertising effectiveness. Journal of Promotion Management, 27(5), 642-672..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2021.1880520]

-

Hetsroni, A., & Tukachinsky, R. H. (2005). The use of fine art in advertising: A survey of creatives and content analysis of advertisements. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 27(1), 93-107..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2005.10505176]

-

Huang, Y. (2020). Validating a modified typology of visual metaphor: Evidence form artful deviation, imagistic elaboration and ad attitude. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(5), 509-527..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2018.1533489]

-

Huang, Y. (2023). Visual metaphors in advertising: An interplay of visual structure, visual context, and conceptual tension. Journal of marketing communications , 1-30..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2023.2177708]

-

Hutton, S. B., & Nolte, S. (2011). The effect of gaze cues on attention to print advertisements. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(6), 887-892..

[https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1763]

-

Indumathi, S., & Nivedhitha, D. (2017). Gender stereotyping in Indian advertisements. Mass Communicator International Journal of Communication Studies, 11(3), 21..

[https://doi.org/10.5958/0973-967x.2017.00016.3]

-

Indurkhya, B., & Ojha, A. (2017). Interpreting visual metaphors: asymmetry and reversibility. Poetics Today, 38(1), 93-121..

[https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-3716240]

-

Jayaraman, J. D., & Jambunathan, S. (2018). Financial literacy among high school students: Evidence from India. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 17 (3), 168-187..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173418809712]

-

Jeong, S. H. (2008). Visual metaphor in advertising: Is the persuasive effect attributable to visual argumentation or metaphorical rhetoric? Journal of Marketing Communications, 14(1), 59-73..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010701717488]

-

Kumari, S., & Shivani, S. (2014). Female portrayals in advertising and its impact on marketing communication-pieces of evidence from India. Management and Labour Studies, 39(4), 438-448..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042x15578022]

-

Lagerwerf, L., van Hooijdonk, C. M., & Korenberg, A. (2012). Processing visual rhetoric in advertisements: Interpretations determined by verbal anchoring and visual structure. Journal of pragmatics, 44(13), 1836-1852..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.08.009]

-

Latała-Matysiak, D., & Marciniak, M. (2021). The influence of the lotus flower theme on the perception of contemporary urban architecture. Space and Culture, 26 (4), 647-655..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/12063312211032353]

-

Lenka, U., Suar, D., & Mohapatra, P. K. (2009). Service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty in Indian commercial banks. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 18 (1), 47-64..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/097135570801800103]

-

Limbu, S., & Mukherjee, K. (2024). Cultural Attributes in Advertising: An Indian Perspective. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30 (1), 1128-1136..

[https://doi.org/10.53555/kuey.v30i1.5988]

-

Mahapatra, M. S., Alok, S., & Raveendran, J. (2017). Financial literacy of Indian youth: A study on the twin cities of Hyderabad-Secunderabad. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 6(2), 132-147..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975216667096]

-

Margariti, K., Hatzithomas, L., Boutsouki, C., & Zotos, Y. (2022). Α Path to our heart: Visual metaphors and "white" space in advertising aesthetic pleasure. International Journal of Advertising, 41(4), 731-770..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1914446]

-

Mohammed, S., Tharayil, H., Gopakumar, S., & George, C. (2020). Pattern and correlates of depression among medical students: an 18-month follow-up study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(2), 116-121..

[https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpsym.ijpsym_28_19]

-

Mulchandani, K., Mulchandani, K., & Attri, R. (2019). An assessment of advertising effectiveness of Indian banks using Koyck model. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 16(4), 498-512..

[https://doi.org/10.1108/jamr-08-2018-0075]

-

Nelson, M. R., & Paek, H. J. (2007). A content analysis of advertising in a global magazine across seven countries: Implications for global advertising strategies. International Marketing Review, 24(1), 64-86. doi.org:10.1108/02651330710727196/full/HTML.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330710727196]

- Nethala, V. J., Pathan, M. F. I., & Sekhar, M. S. C. (2022). A Study on Cooperative Banks in India with Special Reference to Marketing Strategies. The journal of contemporary issues in business and government, 28(4), 584-593..

-

Pant, V., Srivastava, N., Singh, T., & Pathak, P. (2021). Education loan delivery by banks in India: a qualitative enquiry. Banks and Bank Systems, 16 (4), 125-136..

[https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.16(4).2021.11]

-

Pathak, S. (2024). Unravelling the linguistic tapestry: a discursive study of gender portrayal in select Indian electronic advertisement. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 16(1)..

[https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v16n1.02g]

-

Phillips, B. J., & McQuarrie, E. F. (2002). The development, change, and transformation of rhetorical style in magazine advertisements 1954-1999. Journal of advertising, 31 (4), 1-13..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673681]

-

Phillips, B. J., & McQuarrie, E. F. (2004). Beyond visual metaphor: A new typology of visual rhetoric in advertising. Marketing theory, 4(1-2), 113-136..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/14705931040440]

-

Phillips, B. J., & McQuarrie, E. F. (2009). Impact of advertising metaphor on consumer belief: Delineating the contribution of comparison versus deviation factors. Journal of Advertising, 38(1), 49-62..

[https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367380104]

-

Rink, U., Walle, Y. M., & Klasen, S. (2021). The financial literacy gender gap and the role of culture. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 80 , 117-134..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2021.02.006]

-

Ruhina, A., & Sridevi, G. (2021). An evaluation of visual perception visual memory cognitive functions and emotional status among genders in elderly subjects. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International, 330-336..

[https://doi.org/10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i47b33132]

-

Sathye, M. (2010). Indian banking: changing landscape in a globalised era. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 4(4), 399..

[https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbg.2010.032972]

-

Scott, L. M. (1994). Images in advertising: The need for a theory of visual rhetoric. Journal of consumer research, 21(2), 252-273..

[https://doi.org/10.1086/209396]

-

Sczesny, S., Formanowicz, M., & Moser, F. (2016). Can gender-fair language reduce gender stereotyping and discrimination? Frontiers in Psychology, 7..

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00025]

-

Shepherd, D. A., Saade, F. P., & Wincent, J. (2020). How to circumvent adversity? Refugee-entrepreneurs' resilience in the face of substantial and persistent adversity. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(4), 105940..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.06.001]

-

Si, N. (2022). Exploring Whether Female Economic Participation Rates in India are Correlated with Educational Attainment Using a Capability Approach. The Educational Review, USA, 6(11), 776-780..

[https://doi.org/10.26855/er.2022.11.020]

-

Singh, Y., & Milan, R. (2023). Analysis of financial performance of public sector banks in India: CAMEL. Arthritis: Journal of Economic Theory and Practice, 22 (1), 86-112..

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0976747920966866]

-

Sopory, P., & Dillard, J. P. (2002). The persuasive effects of metaphor: A meta-analysis. Human communication research, 28(3), 382-419..

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00813.x]

-

Srivastava, A., & Dey, D. K. (2016). Brand analysis of global and local banks in India: A study of young consumers. Journal of Indian Business Research, 8(1), 4-18..

[https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-05-2015-0061]

-

Van Mulken, M., Le Pair, R., & Forceville, C. (2010). The impact of perceived complexity, deviation and comprehension on the appreciation of visual metaphor in advertising across three European countries. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(12), 3418-3430..

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.04.030]

-

Van Mulken, M., Van Hooft, A., & Nederstigt, U. (2014). Finding the tipping point: Visual metaphor and conceptual complexity in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 43(4), 333-343..

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2014.920283]

-

Venkatesh, V.,Morris, M.G., & Ackerman, P.L.,2000. A longitudinal field investigation of gender differences in individual technology adoption decision-making processes. Organizational behaviour and human decision processes, 83(1), pp.33-60..

[https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2896]

-

Wilson, R. T. (2021). Slogans and logos as brand signals within investment promotion. Journal of Place Management and Development, 14(2), 163-179..

[https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-02-2020-0017]

-

Xiao, J. J., Porto, N., & Mason, I. M. (2020). Financial capability of student loan holders who are college students, graduates, or dropouts. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(4), 1383-1401..

[https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12336]

-

Yu, H. (2011). Visualizing banking and financial products: A comparative study of Chinese and American practices. Journal of technical writing and communication, 41(3), 289-310..

[https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.41.3.e]

-

Zhao, H., & Lin, X. (2019b). A review of the effect of visual metaphor on advertising response. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Economy, Judicature, Administration and Humanitarian Projects (JAHP 2019)..

[https://doi.org/10.2991/jahp-19.2019.7]