Effect of Empathy on Designers and Non-designers in Concept Evaluation

Background Empathy instruction (“please empathize with the person in the narrative”)is often provided when new product concepts are evaluated in a narrative form. However, concept evaluators tend to empathize with users differently; non-designers empathize with them insufficiently whereas designers do so sufficiently. Therefore, we expect that the effect of empathy instruction on concept evaluation will differ depending on the design expertise of individual evaluators. Empathy instruction will benefit non-designers whereas it may not benefit designers. We hypothesize that non-designers evaluate a concept more positively while designers evaluate the same concept more negatively when empathy instruction is provided than when it is not.

Methods We conducted two studies with 74 practitioners (study 1) and 87 undergraduate students (study 2) by asking participants to evaluate a new service concept for long-distance communication. Half of the participants were provided with empathy instruction (“please watch a video clip about a long-distance couple”) and the other half were provided with control instruction (“please watch a video clip about nature). Then, we compared the concept evaluation scores between the two groups.

Results The two studies showed that when the participants received control instruction, their concept evaluation scores between two groups did not differ. However, when they received empathy instruction, non-designers’ concept evaluation scores increased whereas designers’ concept evaluation scores decreased.

Conclusion Our findings highlight the dark side of empathy in concept evaluation. When empathy instruction is provided for narrative concept evaluation, it needs to be used carefully depending on the individual concept evaluators. More discussions are needed for customized empathy.

Keywords:

Concept Evaluation, Narrative Concept, Empathy Instructon, Design Expertise, New Product Development1. Introduction

As companies aim to develop and introduce new products quickly, concepts are often evaluated by cross-functional team members including project managers, marketers, engineers, and designers. This collaborative concept evaluation becomes popular and it occurs among 75% of the new product development (NPD) projects undertaken between 2002 and 2007 (Petersen & Joo 2012). When concepts are evaluated collaboratively, narrative concept and empathy instruction are often provided. That is, a narrative about a hypothetical user’s experience of the product version of the concepts is presented and then a verbal instruction to empathize with the person appearing in the narrative is requested (“please empathize with the person in the narrative”). Prior research has shown that narrative is effective (Van den Hende, et al. 2012) and, when evaluators are dissimilar to users, empathy instruction is recommended (Postma, et al., 2012).

However, empathy instruction may influence individual evaluators differently, in particular, depending on whether they are designers or not. Prior research suggests that designers think differently from non-designers. Beverland (2005), for instance, introduced Peters’ (1994) findings that a legendary fashion designer, Muccia Prada, was constantly “in” the market (market experience) going against being “of” the market (market research). “Rather than using formal market research, Prada drew on her own personal knowledge of ideas gained from many years of in situ observation of global clothing styles” (p. 204). Rieple (2004) also reported that designers scored higher than the people in other occupations in terms of Kirton’s adaption and innovation inventory scale, arguing that designers tend to organize and assess information in an innovative way whereas non-designers depend on generally agreed upon paradigms. Research on the topic of corporate culture also suggests that designers and non-designers may have different “thought-worlds” and the different thinking styles can be reinforced by their daily tasks (Deshpande et al. 1993).

In the present work, we argue that the degree to which designers empathize with target users is greater than non-designers. This is because empathic ability is particularly important for designers and this ability is strengthened by their research and design practice, which finds problems and develops solutions while constantly interacting with users. Therefore, we predict that empathy instruction may benefit non-designers by helping them go beyond market research and appreciate the benefits of the concepts. However, it may not benefit designers because they focus on user’s experience and understand the benefits of the concepts even before empathy instruction is provided. Instead, empathy instruction may harm their ability to understand the benefits of the concepts. This concludes that empathy instruction will be a double-edged sword in the concept evaluation phase.

In order to test whether designers and non-designers evaluate concepts differently when they are asked to empathize with a user, two studies were conducted. We recruited practitioners working in different departments in study 1 and undergraduate students enrolled in different departments in study 2. In each study, half of the participants were provided with an empathy instruction (“please watch a video clip about a long-distance couple”) and the other half were provided with a non-empathy instruction (“please watch a video clip about nature”). To the best of our knowledge, this research is the first attempt to investigate the effect of empathy on concept evaluation. Empathy is recommended in the other phases of NPD including the research and ideation phases to discover unmet needs and develop innovative solutions (Battarbee et al., 2014; Koskinen & Battarbee, 2003; Leonard & Rayport, 1997; Visser & Kouprie, 2008). This research extends the scope of empathy into the concept evaluation phase by demonstrating the different empathy effect on the designers and non-designers.

More importantly, we discover that the contemporary practice of concept evaluation can change its outcomes. Recently, concepts are evaluated collaboratively, narrative is used to help evaluators evaluate concepts from users’ perspectives, and empathy instruction is suggested to overcome the evaluator-user dissimilarity to maximize the narrative effect (Postma et al., 2012). Although narrative was extensively discussed in the past, empathy instruction has been little discussed. As much of prior work suggests that concept evaluation is influenced by subject’ psychological aspects, such as design knowledge, concept ownership, discussion topic, or reasoning (Dong et al., 2015; Nikander & Liikkanen, 2014; Toh & Miller, 2015), our findings showed that it can be influenced by the interaction of instruction and design expertise, suggesting that evaluator’ design expertise needs to be considered when instruction is provided for concept evaluation.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Firstly, we review the literature on concept evaluation, narrative with empathy instruction, and then design expertise to develop two hypotheses. Next, we report two experimental studies and conclude with a discussion of the implications of this research in the area of new product development.

2. Theory

2. 1. Concept Evaluation

The objectives of concept evaluation are to identify a concept with high probability of success, estimate its sales and trial rate in the market, and even devise additional ideas to improve the quality of the selected concept (Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2015). Extensive academic discussion has been made on this phase because it plays a critical role in determining the success of an NPD project (Mahajan & Wind, 1988; Moore, 1982; Zien & Buckler, 1997; Ozer, 1999). Traditionally, potential consumers are invited to evaluate concepts and conjoint analysis is often used when analyzing their responses (Green & Srinivasan 1990). However, as competitive pressure increases and the product life cycle shrinks, cross-functional team members including project managers, marketers, engineers, and designers often evaluate concepts collaboratively in parallel with other NPD phases (Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2015).

Although this collaborative concept evaluation brings advantages such as more informed evaluations or more consistent evaluations mostly due to the expertise of internal team members (Shoormans, Ortt, & De Bont 1995), it also raises a significant problem that evaluators fail to consider users’ perspectives but evaluate concepts from the perspectives of their own professions. For example, studies have found that designers rank their own concepts higher than their counterparts’ ones (Nikander & Liikkanen, 2014), engineers place greater weight on technical feasibility than other criteria (Kazerounian & Foley, 2007; Toh & Miller, 2015), and marketers consider market acceptance more significantly than researchers and developers do (Hart et al., 2003). Even when evaluators do not rely heavily on their own professions, they often select conventional or previously successful concepts in order to avoid potential risk (Ford & Gioia, 2000; Rietzschel, Nijstad, & Stroebe, 2010). Hart et al. (2003) stated that the orientation to the users’ needs should be carried through from research to ideation, but this orientation diminishes with the progress of the NPD process, and when the concepts are evaluated, technical and financial considerations come to the fore. In sum, user orientation needs to permeate into the collaborative concept evaluation phase.

2. 2. Narrative Concept and Empathy Instruction

User orientation is widely instilled in the research and ideation phases through methods such as observation (Black, 1998; Leonard & Rayport, 1997), user involvement (Mattelmäki, 2005; Sanders, 2000), or designers’ engagement (Boess, Saakes, & Hummels, 2007; Buchenau & Suri, 2000; Suri, 2003). In the concept evaluation phase, narrative is often suggested for user orientation (Green & Barock, 2000). When a concept is depicted in narrative form, it shows how a hypothetical user consumes the product version of the concept in his or her own situation, and evaluators “transport themselves into” the user’s storyline. As evaluators perceive the user’s experience vividly and elicit affective reactions, they are able to evaluate the concept holistically (Deighton, Romer, & McQueen, 1989). In sum, narrative builds a temporal connection between evaluators and a hypothetical user by allowing them to personally experience the user’s experience as if the user exists.

Although narrative is effective, it has a critical limitation. When evaluators are dissimilar to a hypothetical user in terms of ethnicity, gender, or age, they fail to transport themselves into the users’ storyline, which results in misunderstanding of the concepts (Postma et al., 2012). In order to overcome this problem, empathy is verbally instructed in practice (“please empathize with the user in the narrative”).

2. 3. Design Expertise

Empathic horizon, the ability to empathize with others, is determined by individuals’ background (McDonagh-Philip & Denton, 1999), and it increases when individuals gain experience (Kouprie & Visser, 2009). We expect that when narrative concept is presented, designers tend to empathize with the users of the narrative more deeply and understand the concept’ benefits more accurately than non-designers. The intuition behind this proposition is rooted from the different nature of their tasks. Designers constantly imagine users who use new products because they need to develop new concepts. In contrast, non-designers do not have to develop new concepts and, therefore, empathy with others will rarely occur to them. In sum, the level of empathy with a user in the concept evaluation phase differs between designers and non-designers.

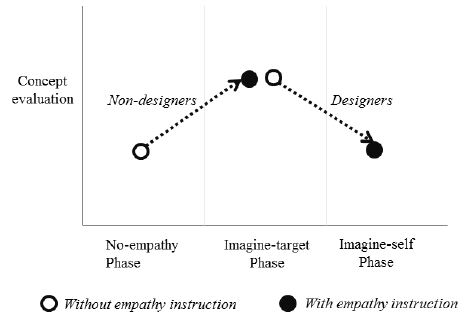

Also empathy is broken down into two separate phases: imagine-target and imagine-self (Batson et al., 1997; Davis et al., 2004; Langfeld, 1967). In the imagine-target phase, people recognize the distinction between themselves and others and, therefore, imagine others’ feelings and experiences indirectly. In the imagine-self phase, the mental representation of self is merged with that of others, and therefore, people imagine others’ feelings and experiences directly. Davis et al. (2004) showed in their study that participants were more likely to report target-related thoughts when they read the imagine-target instruction (“please imagine how he/she feels”), and they were more likely to report self-related thoughts when they read imagine-self instruction (“please imagine how you would feel if you were the person”). In general, the imagine-target phase precedes the imagine-self phase, and in the latter phase, people tend to apply their personal knowledge and experience to others more actively than in the former phase. This proposition may lead empathy instruction to affect designers and non-designers differently. For non-designers, empathy instruction moves them from the no-empathy phase to the imagine-target phase. In contrast, the same empathy instruction moves designers from the imagine-target phase to the imagine-self phase.

As such, we hypothesize that empathy instruction affects designers and non-designers unequally when they evaluate concepts. More specifically, empathy instruction will benefit non-designers who empathize with the user insufficiently. However, it may not benefit designers because designers sufficiently empathize with the user throughout the NPD process. Rather, empathy instruction will lead designers to perceive and evaluate the concepts more critically. Therefore we hypothesize that designers and non-designers are expected to evaluate concepts differently when empathy instruction is provided.

Hypothesis 1: When non-designers are asked to empathize with a target user, they will evaluate a new product concept more positively than when not.

Hypothesis 2: When designers are asked to empathize with a target user, they will evaluate a new product concept more negatively than when not.

3. Study

We tested two hypotheses by conducting two experiments.

3. 1. Study 1

In this experiment, participants were asked to evaluate a new product concept for long-distance communication depicted in a narrative form. Similar to a collaborative concept evaluation, we collected responses from two different groups of people: design practitioners and non-design practitioners. Since half of them were provided with empathy instruction (“please watch a video clip about a long-distance couple”) while the rest were provided with control instruction (“please watch a video clip about nature”), we compared the effect of empathy instruction on concept evaluation within each group of participants.

We recruited 74 participants who were at the time working in the manufacturing industry in Seoul, Korea. In total, 35 participants were male and 39 participants were female. We did not analyse gender because it did not influence the effect of empathy instruction on concept evaluation. In terms of design expertise, 38 participants indicated themselves as designers currently working in the design departments and 36 participants indicated themselves as non-designers currently working in the marketing or engineering departments.

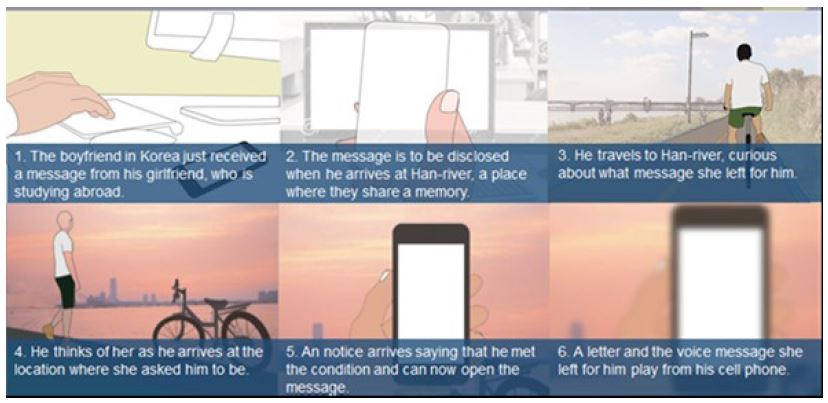

For the experimental stimulus, we used a new communication service concept that was proposed by design students and was not commercialized. It is a new service which helps people exchange emotional reactions with others in remote places while communicating with them (Figure 1). Its narrative comprised of drawing and text to form a user scenario that describes how a long-distant couple use this service.

We employed a 2 (instruction: control vs. empathy) × 2 (design expertise: non-designer vs. designer) between-subjects design experiment (Table 1). We manipulated instruction by asking participants to watch one of the two different video clips before they evaluated the concept (Figure 2).

Participants in the control condition watched a video clip about nature and participants in the empathy condition watched a video clip that depicts the daily life of a long-distance couple living separately. We selected and then edited two video clips carefully in order to control their length and sound; they played for the same duration (170 seconds) and they played with the identical background music by dubbing the original natural sound and the dialogue between two people. After watching one of the two video clips, participants were asked to write a brief description about the content of each video clip to make sure that they paid attention to their own videos.

We checked manipulation and measured concept evaluation through an online survey website. First, we asked participants to evaluate the concept according to the five criteria on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much): (1) innovation, (2) realization possibility, (3) functionality and usefulness, (4) emotional content, and (5) impact. We sourced the five concept evaluation criteria from the Red Dot award (http://www.red-dot.sg/en/jury/judging-criteria/). Note that we dropped aesthetic quality because it does not reflect the early phase of the service concept. To make each concept evaluation criterion clear, we provided the following description to each participant.

- (1) Innovation: Is the concept new?

- (2) Realization possibility: Can the concept be produced from a technological and economical point of view?

- (3) Functionality and usefulness: Does the concept fulfill all requirements of handling, usability, safety, and maintenance? Does it fulfill a need or function?

- (4) Emotional content: What does the concept offer the user beyond its immediate practical purpose in terms of sensual quality, possibilities of a playful use, or emotional attachment?

- (5) Impact: What is the scale of the benefit or impact that the concept has on the problem?

In order to test whether our instruction manipulation was successful, we asked participants to answer the following two questions on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all vs. 7 = very much); (1) how much effort they had invested in imagining the target user of the concept and (2) to what degree they had actually imagined themselves as the target user of the concept. We sourced these two manipulation check questions from the previously published psychology papers on empathy (Batson & Shaw, 1991; Cialdini et al., 1997; Davis et al., 1996; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000).

Manipulation Check. The internal consistency of the participants’ responses to the two manipulation questions, the effort to empathize (M = 5.07, SD = 1.34) and the actual level of imagination (M = 4.74, SD = 1.54), was acceptable (α = .75). Therefore, we averaged the two scores to produce an empathy score and subjected it to a 2 (instruction) x 2 (design expertise) ANOVA (Analysis of variance). We obtained only a main effect of empathy instruction. Participants who watched the video clip about a long-distance couple empathized with the target user more strongly than did participants who watched the video clip about nature (Mcontrol = 4.57 vs. Mempathy = 5.18; F(1,70) = 4.14, p = .05). Neither the main effect of design expertise (p = .83) nor the interaction effect of instruction and design expertise was significant (p = .27). This confirmed that our manipulation of instruction worked as intended.

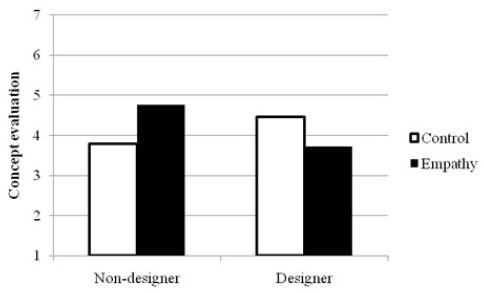

Concept Evaluation. The internal consistency of the participants’ responses to the five questions about a concept, innovation (M = 4.20, SD = 1.65), realization possibility (M = 4.72, SD = 1.52), functionality and usefulness (M = 3.50, SD = 1.64), emotional content (M = 4.78, SD = 1.72), and impact (M = 3.73, SD = 1.63), was high (Cronbach’s α = .87). Our principal component analysis revealed only one component was extracted. It explained in total 66.17% of the total variances and the five criteria were well loaded onto this variable (innovation = .81, realization possibility = .53, functionality and usefulness = .90, emotional content = .86, and impact = .90). Further, our correlation matrix revealed that they were highly correlated each other. Therefore, we averaged the five concept evaluation scores to produce a single concept evaluation score and subjected it to a 2 (instruction) x 2 (design expertise) ANOVA (Figure 3).

We obtained a significant interaction effect of instruction and design expertise (F(1,70) = 8.32, p = .005). Neither the main effect of instruction (p = .69) nor the main effect of design expertise (p = .54) was significant. As hypothesized, non-designers evaluated the concept more favorably when they were instructed to empathize with the target user than when not (simple effects analysis, Mcontrol = 3.79 vs. Mempathy = 4.76; F(1,70) = 5.25, p = .03). In contrast, designers evaluated the concept more negatively when they were instructed to empathize with the target user than when not (simple effects analysis, Mcontrol = 4.46 vs. Mempathy = 3.72; F(1,70) = 3.17, p = .08). We also confirmed that their concept evaluation scores did not differ when they were not instructed to empathize with the target user (simple effects analysis, Mnon-design = 3.79 vs. Mdesign = 4.46; F(1,70) = 2.32, p = .13). However, their concept evaluation scores significantly differed when they were instructed to empathize with the target user (simple effects analysis, Mnon-design = 4.76 vs. Mdesign = 3.72; F(1,70) = 6.87, p = .01), suggesting that empathy instruction drove the effect of design expertise on concept evaluation.

Our first study demonstrated that empathy instruction did not influence concept evaluators equally. It increased concept evaluation scores for non-designers whereas it decreased them for designers. Further, concept evaluation scores did not differ in the control instruction condition whereas they differed significantly in the empathy instruction condition, suggesting that not control instruction but empathy instruction influenced concept evaluation scores. Our findings contribute to the academic discussions on concept evaluation because they firstly tested the role of empathy instruction in the concept evaluation phase and demonstrated its negative effect for designers, calling for a customised approach toward applying empathy instruction.

Although our findings provided fresh insights into researchers and practitioners, we tested our hypotheses by recruiting practitioners. Although field experiments are valid and we found no evidence that their demographic variables explained our findings alternatively, our findings may lack in reliability. Some prior work on empathic horizon suggests that not only experience but also a wide variety of other demographic variables shape how much people can empathize with others (Kouprie & Visser, 2009; McDonagh-Philip & Denton, 1999). Therefore, testing the same hypothesis with different participants is needed.

3. 2. Study 2

In order to test the same hypotheses using different subjects, we conducted the identical study by recruiting undergraduate students.

We recruited 87 undergraduate students in Seoul, Korea. In total, 52 undergraduate students enrolled in the design department and 35 undergraduate students enrolled in the business administration department in the same university participated in this study. They are between the second year and the fourth year, and 25 students are male and 62 students are female. Gender and age were not analysed because these two variables did not influence the effect of empathy instruction on concept evaluation. Most importantly, none of the students had any prior experience of collaborative concept evaluation task, suggesting that difference in experience was not an alternative explanation.

We conducted an identical experiment employing 2 (instruction: control vs. empathy) × 2 (design expertise: non-designer vs. designer) between-subjects design. We used the same experimental stimulus, manipulated instruction in the same way, and checked empathy manipulation and measured concept evaluation in the way identical with study 1.

Manipulation Check. The internal consistency of the participants’ responses to the two manipulation check questions, effort to empathize (M = 4.55, SD = 1.58) and actual level of imagination (M = 4.41, SD = 1.70), was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .72). Therefore, we averaged the two scores to produce an empathy score and subjected it to a 2 (instruction) x 2 (design expertise) ANOVA. We obtained only a main effect of instruction. Participants who watched the video clip about a long-distance couple empathized with their target users more strongly than did participants who watched the video clip about nature (Mcontrol = 3.93 vs. Mempathy = 4.91; F(1,83) = 9.83, p = .002). Neither the main effect of design expertise (p = .97) nor the interaction effect were significant (p = .40). As did study 1, this confirmed that our manipulation of instruction worked as intended.

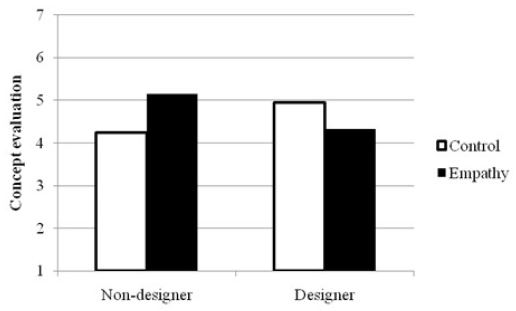

Concept Evaluation. The internal consistency of the participants’ responses to the five questions about a concept, innovation (M = 4.61, SD = 1.47), realization possibility (M = 5.10, SD = 1.73), functionality and usefulness (M = 3.76, SD = 1.43), emotional content (M = 5.78, SD = 1.30), and impact (M = 4.29, SD = 1.35), was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .77). Our principal component analysis extracted only one component and it explained in total 54.58% of the total variances, and the five criteria were well loaded onto it (innovation = .78, realization possibility = .53, functionality and usefulness = .73, emotional content = .82, and impact = .79). Our correlation matrix also revealed that the five criteria were highly correlated. Therefore, we averaged the five concept evaluation scores to produce a single concept evaluation score and subjected it to a 2 (empathy instruction) x 2 (design expertise) ANOVA (Figure 4).

We obtained a significant interaction effect of instruction and design expertise (F(1,83) = 11.36, p = .001). Neither the main effect of instruction (p = .53) nor the main effect of design expertise (p = .80) were significant. Non-designers evaluated the concept more favorably when they were asked to empathize with target users than when not (simple effects analysis, Mcontrol = 4.25 vs. Mempathy = 5.15; F(1,83) = 6.52, p = .01). In contrast, designers evaluated the concept more negatively when they were asked to empathize with target users than when not (simple effects analysis, Mcontrol = 4.95 vs. Mempathy = 4.33; F(1,83) = 4.86, p = .03).

We also confirmed that even though their concept evaluation scores differed when they were not asked to empathize with target users (simple effects analysis, Mnon-design = 4.25 vs. Mdesign = 4.95; F(1,83) = 4.19, p = .04), these scores differed more significantly when they were asked to empathize with target users (simple effects analysis, Mnon-design = 5.15 vs. Mdesign = 4.33; F(1,83) = 7.80, p = .006). Similar to study 1, these findings suggest that not control instruction but empathy instruction drove the effect of design expertise on concept evaluation.

Study 2 replicated the findings obtained in study 1 – that is, empathy instruction increased concept evaluation scores for non-designers whereas it decreased them for designers. We also obtained evidence that empathy instruction determined the effect of design expertise on concept evaluation. In sum, the responses obtained from the undergraduate students in this study showed the identical results obtained from the practitioners in study 1, concluding that our findings are reliable.

4. Conclusion

When concepts are evaluated, they are often depicted in narrative form, and evaluators are often asked to empathize with the target user in the narrative. We raise a question about whether empathy instruction influences evaluators differently depending on their design expertise. We conducted two studies—one with practitioners and one with undergraduate students. Our findings demonstrated that: (1) non-designers evaluated a concept more favorably when they empathized with the target user, and (2) designers evaluated the same concept less favorably when they empathized with the target user. We concluded that empathy instruction influences designers and non-designers differently in the concept evaluation phase.

Our findings are consistent with the proposition that empathy is not a single psychological condition, but it can be broken down into two separate phases: imagine-target and imagine-self (Batson et al., 1997; Davis et al., 2004; Langfeld, 1967). For non-designers, empathy instruction moved them from the no-empathy phase to the imagine-target phase and, therefore, they increased concept evaluation score. In contrast, the same empathy instruction moved designers from the imagine-target phase to the imagine-self phase. As designers applied their personal knowledge and experience actively to target user, they evaluated the concept more critically. In sum, empathy instruction benefits non-designers whereas it harms designers (Figure 5).

This work contributes to the academic discussions on concept evaluation. Prior work shows that it depends on evaluators’ personal characteristics such as openness to innovativeness (Duke, 1994; Shindler, Holbrook, & Greenleaf, 1989), risk-taking attitude (Toh & Miller, 2014), and adoption orientation (Klink & Athaide, 2006). We add design expertise to the list.

This research also expands the scope of empathic design. Traditionally, empathy is extensively discussed in the early phases of the NPD process such as research or ideation (Leonard & Rayport, 1997; Oh & Joo 2012, 2015; So & Joo 2017). We first tested empathy effect in the concept evaluation phase.

Our documented empathy effects can be extended to other phases of NPD. For example, marketers and engineers are also asked to empathize with target users in the ideation workshop. Empathy instruction may help non-designers develop ideas that are appropriate for target users, whereas it may turn designers to become too critical to develop new ideas. All in all, empathy should be carefully instructed only to those who empathize with target users insufficiently in order to achieve desirable results.

Although this research reveals interesting and counter-intuitive findings, it has a critical limitation. Even though we conducted two separatestudies with practioners and undergraduate students, the total number of participants was only 161. In the future, researchers need to recruit more participants to firmly establish the effect of empathy instruction. And we manipulated empathy in a single way in the two studies. Although watching video is an established method to induce empathy, participants can read different instructions or they can look at the same object from different perspectives in order to manipulate empathy. In the future, researchers need to manipulate the level of empathy in different ways and test the same hypotheses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2016S1A5A2A03925841).

Notes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted educational and non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

-

Batson, C. D., Early, S., & Salvarani, G. (1997). Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imagining how you would feel. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 23(7), 751-758.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297237008]

-

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological inquiry, 2(2), 107-122.

[https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0202_1]

- Battarbee, K., Suri, J. F., & Howard, S. G. (2014). Empathy on the edge: scaling and sustaining a human-centered approach in the evolving practice of design. IDEO. https://www.ideo.com/news/archive/2014/01/.

-

Beverland, M. B. (2005). Managing the design innovation-brand marketing interface: Resolving the tension between artistic creation and commercial imperatives. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 22(2), 193-207.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-6782.2005.00114.x]

- Black, A. (1998). Empathic design. User focused strategies for innovation. Proceedings of New Product Development.

-

Boess, S., Saakes, D., & Hummels, C. (2007). When is role playing really experiential? case studies. In Ullmer, B., Schmidt, A., Hornecker, E. Hummels, C., Jacob, R., & Van der Hoven E. (eds.), Proceedings of the 1st international conference on Tangible and embedded interaction (pp. 279-282). ACM.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/1226969.1227025]

-

Buchenau, M., & Suri, F. J. (2000). Experience prototyping. In Boyarski D. & Kellogg W.A. (eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd conference on Designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques (pp. 424-433). ACM.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/347642.347802]

-

Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C., & Neuberg, S. L. (1997). Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: When one into one equals eneness. Journal of personality and social psychology, 73 (3), 481-494.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.3.481]

- Crawford, C. M. & Di Benedetto, C. A. (2015). New Products Management. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

-

Davis, M. H., Conklin, L., Smith, A., & Luce, C. (1996). Effect of perspective taking on the cognitive representation of persons: a merging of self and other. Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(4), 713-726.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.713]

-

Davis, M. H., Soderlund, T., Cole, J., Gadol, E., Kute, M., Myers, M., & Weihing, J. (2004). Cognitions associated with attempts to empathize: How do we imagine the perspective of another?. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(12), 1625-1635.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271183]

-

Deighton, J., Romer, D., & McQueen, J. (1989). Using drama to persuade. Journal of Consumer research, 16(3), 335-343.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/209219]

-

Deshpande, R., Farley, J. U.,& Webster Jr. F. E. (1993). Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: a quadrad analysis. The journal of Marketing, 57(1), 23-37.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1252055]

-

Dong, A., Lovallo, D. & Mounarath, R. (2015). The effect of abductive reasoning on concept selection decisions. Design Studies, 37, 37-58.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2014.12.004]

-

Duke, C. R. (1994). Understanding customer abilities in product concept tests. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 3(1), 48-57.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/10610429410053086]

-

Ford, C. M. & Gioia, D. A. (2000). Factors influencing creativity in the domain of managerial decision making. Journal of Management, 26(4), 705-732.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600406]

-

Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 708-724.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708]

-

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(5), 701.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701]

-

Green, P. E. & Srinivasan, V. (1990). Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. Journal of Marketing, 54 (October), 3-19.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1251756]

-

Hart, S., Hultink, E. J., Tzokas, N., & Commandeur, H. R. (2003). Industrial companies' evaluation criteria in new product development gates. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20(1), 22-36.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5885.201003]

-

Kazerounian, K. & Foley, S. (2007). Barriers to creativity in engineering education: A study of instructors and students perceptions. Journal of Mechanical Design, 129(7), 761-768.

[https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2739569]

-

Klink, R. R., & Athaide, G. A. (2006). An illustration of potential sources of concept-test error. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(4), 359-370.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2006.00207.x]

- Koskinen, I. & Battarbee, K. (2003). Introduction to user experience and empathic design. In Koskinen, D., Battarbee, K., and Mattelm-ki, T. (eds.), Empathic design: User experience in product design (pp. 37-50). Helsinki: IT Press.

-

Kouprie, M. & Visser, F. S. (2009). A framework for empathy in design: stepping into and out of the user's life. Journal of Engineering Design, 20(5), 437-448.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09544820902875033]

- Langfeld, H. S. (1967). The aesthetic attitude. Port Washington: Kennikat Press.

- Leonard, D. & Rayport, J. F. (1997). Spark innovation through empathic design. Harvard business review, 75, 102-115.

-

Mahajan, V. & Wind, Y. (1988). New product forecasting models: Directions for research and implementation. International Journal of Forecasting, 4(3), 341-358.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2070(88)90102-1]

-

Mattelmäki, T. (2005). Applying probes-from inspirational notes to collaborative insights. CoDesign, 1(2), 83-102.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15719880500135821]

-

McDonagh-Philip, D., & Denton, H. (1999). Using focus groups to support the designer in the evaluation of existing products: A case study. The Design Journal, 2(2), 20-31.

[https://doi.org/10.2752/146069299790303570]

-

Moore, W. L. (1982). Concept testing. Journal of Business Research, 10(3), 279-294.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(82)90034-0]

-

Nikander, J. B., & Liikkanen, L. A. (2014). The preference effect in design concept evaluation. Design Studies, 35(5), 473-499.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2014.02.006]

- Oh, D. & Joo, J. (2012). Perspective-taking method for user experience research. Archives of Design Research, 25(3), 235-245.

-

Oh, D., & Joo, J. (2015). Effect of mechanical perspective-taking method on evaluating user experience. Archives of Design Research, 28(1), 219-231.

[https://doi.org/10.15187/adr.2015.02.113.1.219]

-

Ozer, M. (1999). A survey of new product evaluation models. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(1), 77-94.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0737-6782(98)00037-X]

- Peters, T. (1994). The pursuit of wow!. New York: Random House.

- Petersen, S., & Joo, J. (2012). Improving Collaborative Concept Evaluation Using Concept Aspect Profile. In D.K.S. Swan, S. Zou, (eds.), Interdisciplinary Approaches to Product Design, Innovation, & Branding in International Marketing (pp.207-222). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Postma, C. E., Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E., Daemen, E., & Du, J. (2012). Challenges of doing empathic design: experiences from industry. International Journal of Design, 6(1), 59-70.

-

Rieple, A. (2004). Understanding why your new design ideas get blocked. Design Management Review, 15(1), 36-42.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2004.tb00148.x]

-

Rietzschel, E., Nijstad, B., & Stroebe, W. (2010). The selection of creative ideas after individual idea generation: choosing between Creativity and Impact. British Journal of Psychology, 101(1), 47-68.

[https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609X414204]

-

Sanders, E. B. N. (2000). Generative tools for co-designing. In Scrivener, S.A.R., Ball, L.J., and Woodstock, A. (eds.), Collaborative design (pp. 3-12). London: Springer-Verlag.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-0779-8_1]

-

Schindler, R. M., Holbrook, M. B., & Greenleaf, E. A. (1989). Using connoisseurs to predict mass tastes. Marketing Letters, 1(1), 47-54.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00436148]

-

Schoormans, J. P. L., Ortt, R. J., & De Bont, C. J. P. M. (1995). Enhancing concept test validity by using expert consumers. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 12(2), 153-162.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5885.1220153]

-

So, C. & Joo, J. (2017). Does a persona improve creativity? The Design Journal, 20(4), 1-17.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1319672]

- Suri, F. J. (2003). Empathic design: Informed and inspired by other people's experience. In Koskinen, I., Battarbee, K., and Mattelmäki, T. (eds.), Empathic design, User experience in product design (pp.51-58). Helsinki: IT Press.

-

Toh, C., & Miller, S. (2014). The role of individual risk attitudes on the selection of creative concepts in engineering design. ASME Design Engineering Technical Conferences, Buffalo, NY.

[https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2014-35106]

-

Toh, C. A., & Miller, S. R. (2015). How engineering teams select design concepts: A view through the lens of creativity. Design Studies, 38, 111-138.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2015.03.001]

-

Van den Hende, E. A., Dahl, D. W.,Schoormans, J. P. L., & Snelders, D., (2012). Narrative transportation in concept tests for really new products: The moderating effect of reader-protagonist similarity. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29(1), 157-170.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00961.x]

- Visser, F. S. & Kouprie, M. (2008, October). Stimulating empathy in ideation workshops. In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008 (pp. 174-177). Indiana University.

-

Zien, K. A. & Buckler, S. A. (1997). From experience dreams to market: crafting a culture of innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 14(4), 274-287.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0737-6782(97)00029-5]